Indian Farmers: A Bitter Harvest

By Moin Qazi

29 December, 2015

Countercurrents.org

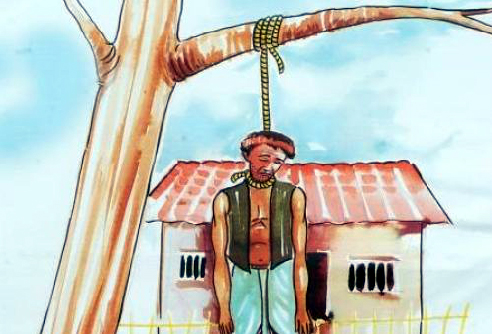

The agricultural sector is still India's largest employer: 58% of rural households depend on it for their livelihood. And yet, since the early 1990s, India has seen a spate of headlines highlighting farmers' suicides. According to government data, 14,000 farmers killed themselves in 2011--this was 47% higher than the national average of all deaths caused by suicides. In fact, since 1995 when the government began keeping records, nearly 300,000 farmers have taken their own lives until 2014.

The situation is dire. But it may just be worse than it looks. A study published in the British medical journal The Lancet found that the suicide figures in India were being under-reported. P. Sainath, journalist and author of Everybody Loves a Good Drought agrees entirely. "Some state governments and union territories are now declaring the number of farmer suicides as zero," he says. "This was accomplished by changing the methodology of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) itself." In 2014, Sainath explains, the NCRB introduced new categories to classify data and then shifted farmer suicides to those new categories, hence lowering the 'official' tally. Take Karnataka: In 2014, it saw 321 farmer suicides--a huge drop from 1403 the previous year. But the number of suicides labelled 'Others' saw a rise of 245%. Coincidence? No, just a neat and despicable trick.

.

That indebted Indian farmers have taken their own lives in horribly high numbers is true. But it’s a complex story that surprisingly few in the media have attempted to unravel. The answer to the question as to why the farmers are committing suicides lies in a combination of factors such as crop failure, shifting to more profitable but risky (in terms of output, quality and prices) cash crops like cotton/ sugarcane/ soyabean, exorbitant rate of interest and other terms and conditions of loans availed from money lenders, lack of non farm opportunities, unwillingness to adopt to scientific practices, non availability of timely credit from formal channel, absence of proper climate/ incentive for timely repayment of bank loan, etc. At some places even though water is available but can’t be exploited fully due to insufficient power supply. Huge expenditure on children’s education and sudden demand of money for health considerations and marriage, etc. in the family are also major contributors for stress in farming community. Inconsistency of rainfall during monsoon, absence of support mechanism for marketing of agriculture produce also contributed to uncertainty and financial risk of the farmers.

These farmers and their families are among the victims of India’s longstanding agrarian crisis. Economic reforms and the opening of Indian agriculture to the global market over the past two decades have increased costs, while reducing yields and profits for many farmers, to the point of great financial and emotional distress. As a result, smallholder farmers are often trapped in a cycle of debt. During a bad year, money from the sale of the cotton crop might not cover even the initial cost of the inputs, let alone suffice to pay the usurious interest on loans or provide adequate food or necessities for the family. Often the only way out is to take on more loans and buy more inputs, which in turn can lead to even greater debt. Indebtedness is a major and proximate cause of farmer suicides in India.

The World Bank data shows that only 35% of India’s agricultural land is irrigated (artificial application of water to land or soil). This means that a huge 65% of farming depends on rain, something on which the government has no control. Small and marginal farmers also do not have access to institutional credit. Most of them depend on village traders, who are also moneylenders, giving them crop loans and pre-harvest consumption loans. The superior bargaining power of village traders and the middlemen means that the prices received by farmers are low. Higher farm labour input price and depleting ground water resources (which means higher prices of generator sets) add to their woes..Subsidies, once a linchpin of Indian economic policy, have dried up for virtually everyone but the producers of staple food grains. Indian farmers now must compete or go under. To compete, many have turned to high-cost seeds, fertilizers and pesticides, which now line the shelves of even the tiniest village shops.

There’s a tendency to appear dismissive of the real life struggles of the Indian agrarian class with two words – “go organic”. As an ideal, it’s perfect. Yet it’s not that simple. A farm that’s been hammered with years of chemical abuse needs some detox time in order to qualify for an organic standard certificate. That means three years of farming organically without the perks of selling at organic prices. The fear of lower yield for farmers who are oftentimes below the poverty line is enough to keep them on the smack.

There just seems to be glib talks on restoring soil quality, rationalisation of aquifer use, protecting forests as catchment areas or securing the land and livelihood of the tribal poor. Forget the so-called green concerns often ridiculed as Luddites’ fad, the apparent big thrust on agriculture rings astoundingly hollow without any attention to the recommendations of the 12th Plan to address the soil health crisis. The suicidal fertiliser subsidies continue, encouraging farmers to use chemical fertilisers in ever larger quantities, triggering rapid soil degradation. There is no talk or funds yet to try natural alternatives to revive the dying fields Thanks to Monsanto blasting through and taking over the seed market, other cotton seed varieties have died on the vine and are hardly available anymore in cotton growing regions like Vidarbha, Maharashtra and other parts of India. We must keep in mind that these farmers have been growing cotton for centuries, and were always able to eke out a living. That was with conventional seeds, which are suited to the region and don’t need much water, because there isn’t any.

It is silly to attempt to develop 600,000 villages because it cannot be done. The future is deserted villages because people vote with their feet when they get the chance to move to a city. Only in very rich economies do people have the resources to live comfortably in villages. India cannot afford to live in villages; it is not that rich

Loan waivers and relief packages may mitigate farmers' distress in the short run, but the problem requires comprehensive solution that addresses the issues of crop yield, availability of farm inputs and loan from banking institutions, assured irrigation, cold storage and marketing facilities and fair pricing policies. Moreover, we need to create of alternative source of income for farmers by way of non-farming activities like dairy, poultry, fisheries etc.

Moin Qazi is a well known banker, author and Islamic researcher .He holds doctorates in Economics and English. He was Visiting Fellow at the University of Manchester. He has authored several books on religion, rural finance, culture and handicrafts. He is author of the bestselling book Village Diary of a Development Banker. He is also a recipient of UNESCO World Politics Essay Gold Medal and Rotary International’s Vocational Excellence Award. He is based in Nagpur and can be reached at [email protected]