Fukushima: What The Children Have To Say

By Ruthie Iida

18 February, 2012

Dianuke.org

Thirteen-year-old Kenji shook his mane of tousled black hair and clutched his head with disgust. “I don’t care whether Japan uses nuclear energy or not! Everyone has a different opinion anyway, and it gives me a headache to think about it. It’s too difficult! We kids should leave that stuff to the adults and be done with it!” Kenji was having a rather extreme reaction to my line of questioning, and was probably getting hungry and tired as well, since it was nearly eight in the evening. I called it a night, and let he and his friends go home to eat dinner and watch their favorite TV quiz shows.

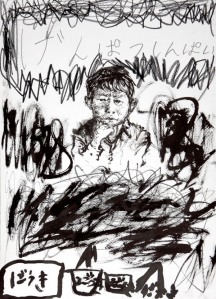

Drawing by Naoya, age 8, Koriyama City. "I'm worried about nuclear power plants" (Geoff Read)

I am actually a mild-mannered English teacher. As a rule, I do not provoke children to tear their hair out over moral dilemmas, but for one week, I had decided to conduct interviews with my older students (sixth, seventh, and eighth graders, with three older high school students thrown in for good measure) to see what they thought of the situation in Fukushima and how they felt about nuclear energy. I had mailed their mothers in advance to ask permission, and most of them were a bit nervous about sitting down with a microphone in the middle of the floor, doing something outside of the usual routine. The boys acted goofy and the girls refused to say anything at all for the first few minutes, but I resolutely forged ahead, and they eventually became involved with the questions in spite of themselves. Some of their responses surprised me, some were disappointing, and a few were worthy of applause. I questioned them all in small groups to minimize stage-fright and peer pressure ( as in, “Twenty kids have already agreed, so I ‘d better agree as well…” ), and here’s what I learned from the twenty-three children who participated: ten boys and thirteen girls. The interviews were done in Japanese, and I’ll try to put their words into natural-sounding Jr. High School English.

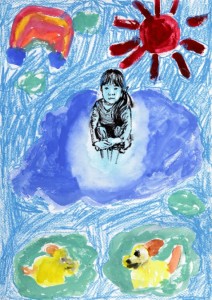

Drawing by Kurumi, age 7, Koriyama City, Fukushima. "Flying with Dogs" (Geoff Read)

First, I asked about their schools (they represent four different public schools in the neighborhood, plus two private schools), and whether or not any evacuees from Tohoku were in their classes. Not surprisingly, children from two of the three public schools reported “yes”, and that the new students were from Fukushima. ”Well, how are they doing?” I asked. “Are they making friends, and are Hadano kids treating them alright?” Hiromasa-kun from School A. never blinked, replying that the girl he knew was having no troubles at all, and had plenty of friends. Sayaka-san, from the same school, confirmed this, adding, “Man, she’s like the most popular kid in the school!” Keiko-san from School B. also knew of a Fukushima student in her school; no problems fitting in, she said, and knew of no bullying incidents. Tadashi-kun from School C. was disappointed that there were no Fukushima students in his school. “I want at least one to come!” he said. “If they did, I wouldn’t bully them. Just the opposite: I’d want to play with them and make them happy if they were sad after losing a relative or something.” Tadashi is an unusually outspoken and sweet-natured boy, whose words flow easily, straight from the heart. Pretty rare (and rather uncool) in a sixth-grade boy, but he’s sporty as well, and his friends don’t give him a hard time. Whatever the case, if Fukushima kids were being bullied in the Hadano schools, my students knew nothing about it. “I heard some rumors…” said Rina-san hesitantly, but that was as far as I got.

Next, I asked them to imagine that they lived in Fukushima, close to the evacuation zone. They were “allowed” to live there legally, but the area still had a high level of radiation, and they wouldn’t be able to play outside for long periods of time. Would they want to stay there, or would they rather evacuate to a new, safer place where they would have more freedom? I purposely left their parents out of the equation, saying that “Your mom and dad have left it up to go. They’ve agreed to do what you want.” I had some ideas about what my students might say, but still it was surprising to hear how quickly they formed their answers and defended their positions.

Drawing by Yamato, age 13, Fukushima City. "Let's be bright, like Sunflowers" (Geoff Read)"

As I expected, many students (eleven in all) answered without hesitation that they wouldnot leave Fukushima. Their reasons? They would not want to leave their hometowns, friends or club activities “I couldn’t leave my band,” said Masaya-kun, one of the three high school students. “We’ve been together for a year now.” Well, a year is a long time in the life of a sixteen-year-old. Some said that even if they got sick from radiation exposure later on in life, at least they could be together with their friends. Kanako-san, from School A. said she didn’t believe there was any real danger from radiation exposure anyway. Ryou-kun, from School B. said he had “never given a thought to radiation exposure” before. ”I’d want to stay and help clean up and rebuild my hometown,” said Hiroki-kun, a serious, soft-spoken boy from School A. They were all in agreement that their relationships and ties to their hometown were more important than fleeing from an invisible enemy (that they cannot yet conceive of, and are not convinced really exists).

The remaining students were divided. Three of them were unable to decide without knowing what their friends would do. “Well, if my friends all decided to evacuate, there’d be no reason for me to stay….” said Fumiko-san, looking uncomfortable. The girl next to her immediately agreed, and Haruto-kun declared he would wait till the end of sixth grade before evacuating. ”That way I could graduate with all my friends, and then I’d decide what to do.” he declared.

Nine out of the twenty-three declared they would evacuate. Knowing all the students fairly well, I can vouch for the fact that these were the outgoing and strong-willed kids, who would have very little trouble assimilating anywhere. Most of them were the ones who sang loudly and without inhibition in first and second grade (you think all first graders like to sing?! Hah! Not in Japan! ) , and who were, as they got older, not afraid to admit they liked studying. Some were even brave enough to come to English practice sessions rather than soccer practices. Although they make different choices than their peers, they can also “read the air” (get along smoothly with those same peers, without deliberately or accidentally antagonizing them) and are well-liked and admired in their schools and in my classes. Two students in particular spoke well, using both confidence and logic. The first was Kenji-kun , who stated simply, “Well, if I couldn’t play outside, why would I want to stay there?? Besides, there could be another tsunami or earthquake, making an even bigger mess! I’d get the heck out!” The second, and most interesting comment on evacuation came from Keiko-san, a tall, intelligent, no-nonsense girl. “Well, in reality,” she said, ”we’re all going to leave our friends and strike out on our own as adults, aren’t we? So it’s just like starting the process a bit earlier. I’d rather get to a safe place as soon as possible rather than waiting around!” Though I was doing my best to preserve a neutral stance, I couldn’t stop myself from muttering, “Go, Keiko!” and several girls looked at her, wishing they could be that cool–or brave– themselves. No-one changed their stance because of her comment, though, and she remained the only one in her own class in favor of evacuating.

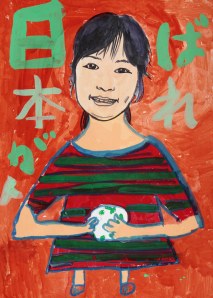

Drawing by 8 year old girl from Fukushima. "Ganbare, Nippon!" (Geoff Read)

Another question I asked was about pressure that some students are reportedly experiencing in Fukushima public schools. “If your mother insisted you bring a box lunch full of vegetables and rice from safe regions of the country, but your teacher insisted you eat the school lunch (containing Fukushima vegetables and milk), what would you do??” This question proved to be even more troubling to many of the students, especially the boys. Only two children feared their teachers more than their mothers, and declared that they would eat the school lunch without complaint. Seven others thoughtfully proposed various compromises, such as eating both ( boys, who were confident in the voracity of their own appetites), eating half of each, or, in the case of one very troubled-looking boy, eating neither. “I wouldn’t have any appetite in that situation anyway,” he confessed sadly. The remainder of the students proudly proclaimed (boasted?) that they would complain to the teacher and eat their mother’s box lunch. ”I’d tell that teacher to quit messing with us!” said Tadashi-kun from School C. with mounting excitement, while Kenji-kun, who said that all this gave him a headache, declared, “No way! Stories like that must be lies! I’d never listen to a teacher like that!” Anna-san, an older private school girl, said quietly, “Obviously, I’d follow the orders of the adult who really cared about me. I know my mother loves me and that’s why she would make me a special box lunch; the teacher is just following a school rule without caring about us personally, so I’ve no obligation to him at all. I’d eat my mother’s lunch.” Again, I had to restrain myself from applauding here, and some of the other girls looked impressed, too. The school lunch/box lunch, teacher/mother dilemma was one that every student could relate to, and it challenged them to take a stand against one of two authority figures in their lives (fathers are not authority figures here , but that’s a different topic altogether). Other questions provoked blank stares and only a few comments, but this one struck a gold mine of emotions.

Before wrapping up each fifteen minute session ( short, but we did these talks in the evening, after their regular English lessons, and I was acutely aware of rumbling stomachs and stifled yawns), I asked each of them what they felt about nuclear power. “Do you want to see all of Japan’s nuclear power plants shut down? Or do you think the country should continue to rely on them? Or should we use alternative energy sources??” By now, readers of this blog know where I stand, but my students did not, and I was determined not to influence their answers with my own opinions. But, as my friend Joseph notes, kids are influenced by their parents’ views, and the answers I got here would doubtless be a refection of what they heard in discussions at home. Still, this was the big question, and needed to be asked. I had already asked how many of them were watching the news on a daily basis; around half they kids were. And surprisingly, all the students agreed that the situation in Fukushima was not being discussed at school. In other words, a good number of students were not watching the news, hearing nothing about Fukushima at school, and probably not discussing the situation at home. What kind of opinion would these kids have? Holding my breath, I waited to see who would say what. And the results were…..

Out of twenty-three, nine were brave enough to speak out in favor of shutting down all of Japan’s nuclear plants, the sooner the better. “People say than nuclear power is cheaper,” said Tadashi-kun, “but life is more important than money. Too many people have been hurt by the Fukushima Daiichi accident!” The practical and cool-headed Keiko said, “I think of what happened to the people in Fukushima, and I can’t imagine going back to a nuclear society. I can’t help wondering what it must be like for people in Tohoku…..” And certainly, every student expressed sympathy for the citizens of Fukushima. But most students came down strongly on the side of compromise. They offered all manner of suggestions, such as “half nuclear/ half solar”, or “doing away with nuclear power veeeery slowly”, or ”building the kind of nuclear power plant that absolutely won’t break.” Or “building more nuclear power plants in Japan, but not near me!” More than a few seemed worried about Japan’s debt problem (these were the kids who’d been listening to their parents and watching the news) and were convinced that the country would fall into deep financial straits by attempting to develop forms of alternative energy. Others said that alternative energy sources could never produce enough power to satisfy their electricity-guzzling country. I wanted to remark that electricity-guzzling was a factor that did not have to be permanent; average citizens and large corporations alike have reduced their energy consumption drastically since the quake, and it has not been all that painful. In any case, on the subject of nuclear energy, the students’ opinions were scattered all across the board. This was the point when Kenji-kun clutched his head in despair, howling, “This is too difficult! We should just let the adults deal with everything!”

Drawing by Erika, age 17, Koriyama City, Fukushima. (Geoff Read)

And that’s what my students had to say, in a nutshell. As for my own thoughts……well, it ‘s clear that many Japanese children literally fear change, and were raised by mothers who probably fear change themselves. Although my students assured me that the Fukushima students who have evacuated to their schools are fitting in just fine ( and are, in fact, wildly popular in some cases), if they themselves had the choice to evacuate they would decline, out of fear. Not fear of bullying, but fear of the possibility of bullying. Here’s a quote from a wonderful blog entitled Strong Children Japan. The author, Geoff Read, is a Japan-based artist from the UK who works with children who have suffered emotional distress. He talks with them, and they create portrait pictures together based on the child’s dreams, wishes, or worries. The drawings I have included in this entry are all from his Strong Children project, and there are many more worth seeing. The quote is from the mother of a girl named Hanako, whose picture appears in his blog . Hanako’s mother writes,”Our family has decided to keep living in Fukushima….When people say `All mothers in Fukushima, be brave and evacuate from there!’ I feel pain. I just cannot make that decision because I read about Fukushima residents who evacuated to somewhere else and the children got bullied by local children. Also, I can’t help being concerned about work, money, and the stress that might be caused by starting life in a completely new place as a stranger.”

Hmmmm…..I feel this mother’s pain, but I also hear the word “might”. She’s more afraid of what might happen in a new place than of the danger of an accumulation of internal radiation. I am tempted to feel impatient with this line of thinking. I remind myself, however, to stay calm and sympathetic, remembering that government officials, school principals, and other figures of authority have led women like Hanako’s mother to believe that they are safe. Or at least “not in immediate danger”. Surely if this woman truly felt her situation dangerous, she would not hesitate to leave, for the sake of Hanako. I want to believe this.

Other families do not have the luxury of choosing whether or not to evacuate, as they are in dire financial straits. It is certain that if the central government provided financial assistance, many more would choose to leave, and Fukushima women activists are working round the clock pressuring the central government to provide funds for families who wish to evacuate. Children of mothers who are able but unwilling to evacuate are placing their trust in adults to make decisions for them and tell them what to do next, as Hanako’s mother is probably trusting in government officials. Neither children nor adults have been used to questioning authority (at least openly), and truly the betrayal of the people of Fukushima by the central government has been a difficult reality to come to grips with. It’s something that no-one wants to believe, and something that sounds like a bad soap opera rather than reality. ”Fukushima produce shipped abroad as aid“?? We hear the news and think, surely not. ”Radioactive rubble burned in Tokyo bay“?? Again, we think, yeah, right. ”Japan selling nuclear power plants abroad“? That was the hardest for me to swallow. And the list goes on. It seems that those in charge are not doing such a good job of it–okay, they’re doing a terrible job–and that everyone, children included, needs to be thinking for themselves and being proactive these days.

I was pleased, in the end, with the response from my own students. Knowing the reluctance of Japanese to stand out in any way (this is called “medatsu”), I did not expect so many kids to take such a firm stand and to express themselves so clearly. While some attempted to avoid conflict by finding a compromise and others wanted to avoid making any decision at all, more than a third of the students were not afraid to consider the unknown: a move from their beloved hometown. They also declared themselves willing to face punishment from an authority figure (the teacher promoting school lunches) , and were able to come down firmly on the side of “datsu-genpatsu”, or the shutting down of nuclear plants. These kids are already leaders in their own sphere, and will go on to think more, say more, do more, and make a difference in their world. As Geoff Read, the man behind the Strong Children Japan project writes, “…no record of important historical events, or thinking about policy choices or ethics for that matter, can be complete without including children.” And he’s right. There’s been a whole lot said about children in Tohoku (they are pitiful….no, they are strong! ….no, they are victims…ad infinitum…) but has anyone really been listening to what they have to say in the matter? The adults sure aren’t making sense these days, and I’m more than ready to give the children a chance. Want to see what children are capable of? Good! Take a look at this video if you’re a music lover. Take a look even if you’re not, and you might become one. It’s a recording of a choral group from a Fukushima high school who have taken either the silver or the gold medal in national choral competitions for several years running. Enjoy what you hear, and think about the children of Japan. Their voices deserve to be heard.

Ruthie Iida has lived, worked, and raised her children in Japan for thirteen years. When not teaching English, she writes about changes in post 3-11 Japan and lends her support to Japan’s anti-nuclear movement when and wherever she is able. Her wonderful blog - Kanagawa Notebook – is a rare source of humane stories on life in Japan after Fukushima

Comments are not moderated. Please be responsible and civil in your postings and stay within the topic discussed in the article too. If you find inappropriate comments, just Flag (Report) them and they will move into moderation que.