Go And Tell Your Kids The Story Of Peter Norman

By N. Jayaram

15 June, 2012

Opendemocracy.net

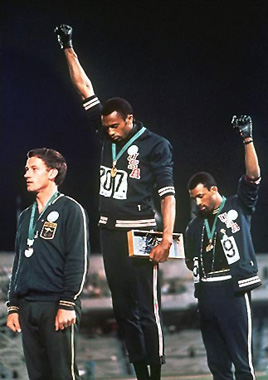

Tommie Smith (centre) and John Carlos (right) showing the Black Power salute in the 1968 Summer Olympics while Silver medalist Peter Norman (left) wears an OPHR badge to show his support for the two Americans.

It is one of the defining images of the 20th century and a symbol of the struggle for human rights and racial equality: Three men took part in a defiant gesture at the Mexico Olympics in 1968. Two raised black-gloved fists. All three wore badges of the Olympic Project for Human Rights.

They were ostracized by their countries and suffered for having dared to differ. Two of the three men were eventually rehabilitated and are today deemed heroes, the third died officially unsung and unhonoured .

That third man was Peter Norman of Australia, who would have been 70 years old on 15 June 2012.

"He didn't raise his fist, but he did lend a hand,” said Tommie Smith, the Black American gold medallist in the 200 metres event. It was the silver medallist Norman’s idea that Smith share his gloves with his fellow Black compatriot John Carlos, the bronze winner, who had left his pair behind in his room. Which is why in that picture, Smith has his right fist aloft and Carlos his left.

"I believe that every man is born equal and should be treated that way," Norman is reported to have said after the ceremony. "Because I was sympathetic to their cause I became part of it," he recalled in a 2005 interview. He had a Salvation Army upbringing and was not unmindful of the treatment of Aboriginal people in his own country.

Norman's time of 20.06 seconds is an Australian 200m record to this day, but he was not allowed to take part in the Munich Olympics of 1972 and was not feted in 2000 when Sydney hosted the Olympics.

Smith and Carlos were packed back home after their human rights salute of 16 October 1968, now more commonly referred to as the Black Power Salute. The International Olympic Committee of the day condemned them as did US media. "If I win, I am American, not a black American,” Smith said. “But if I did something bad, then they would say I am a Negro. We are black and we are proud of being black. Black America will understand what we did tonight."

All three men suffered upheavals in their personal lives. The two Americans had to wait until the 1980s to be ushered back into the limelight and more years to be celebrated as national heroes. While Norman did not receive an immediate formal reprimand, he remained neglected. At the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, it was the US athletic team that invited him to their lodgings. When he died in 2006, Smith and Carlos flew to Australia to act as pallbearers in a mark of respect for a comrade who had been solidly behind their historic gesture.

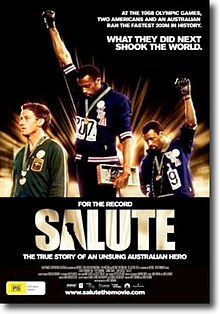

His nephew Matt Norman has made an award-winning film, Salute , enabling a new generation of Australians and others to learn of his significant role in the event.

Several generations of Americans have since come of age hearing about and discussing that gesture. In these times of social networking sites, vast numbers of people around the world display images of the salute on their profile pages.

Akaash Maharaj, former head of Canada’s Equestrian team and who is of Indian ancestry, has said: "In that moment, Tommie Smith, Peter Norman, and John Carlos became the living embodiments of Olympic idealism. Ever since, they have been inspirations to generations of athletes like myself, who can only aspire to their example of putting principle before personal interest. It was their misfortune to be far greater human beings than the leaders of the IOC of the day."

The collaboration of Smith, Norman and Carlos was not an isolated incident of its kind. Around the world, people have since reached out across racial, religious and ethnic divides to strike a blow against discriminatory structures.

Aboriginal Australian Cathy Freeman sparked controversy as she carried the Australian and the Aboriginal flags whilst running victory laps after winning the 200 metres and 400 metres races at the 1994 Commonwealth Games in Canada. By then, however, Australia seemed to have matured somewhat and she did not suffer for her actions.

The decades long project to dismantle Apartheid in South Africa and to usher in multi-racial democracy would not have succeeded without cooperation among Whites, Coloureds and Indians. White lawyers and politicians such as Bram Fischer and George Bizos fought court cases alongside the likes of Nelson Mandela. Ahmed Kathrada has remained Mandela’s life-long confidant, while Joe Slovo of the South African Communist Party and his wife Ruth First, who was killed with a parcel bomb while in exile in Mozambique, lent yeoman support to the struggle of the African National Congress.

Mindful of the potential strength of such inter-racial and inter-religious coalitions, the Israeli establishment has been consistently harsh on Jewish leaders and intellectuals who sympathise with the plight of the Palestinians.

But such coalitions will have to be painstakingly built and sustained, be it in the Middle East, in China between ethnic minorities and the Han majority, in Burma between minority nationalities and the Burman establishment or in India across religious and caste divides.

Nelson Mandela recognized the power of rainbow coalitions and insisted on making the Whites, including Afrikaners, feel at ease in the new South Africa: in one of most electrifying moments in sporting history, he donned the Springbok jersey after the finals of the 1995 Rugby World Cup. His gesture has been hailed in print and in film.

Peter Norman’s humbler contribution needs wider recognition. Prime Minister Julia Gillard, a right-winger in the Australian Labor Party, is unlikely to initiate official rehabilitation of Norman. That may have to await a more enlightened government in Canberra.

But at least Salute , the film, deserves wide viewing. The words of John Carlos at Norman’s funeral have to be heeded by Australians and people all over the world: “Go and tell your kids the story of Peter Norman.”

But at least Salute , the film, deserves wide viewing. The words of John Carlos at Norman’s funeral have to be heeded by Australians and people all over the world: “Go and tell your kids the story of Peter Norman.”

N. Jayaram is a journalist now based in Bangalore after more than 23 years in East Asia (mainly Hong Kong and Beijing) and 11 years in New Delhi. He was with the Press Trust of India news agency for 15 years and Agence France-Presse for 11 years and is currently engaged in editing and translating for NGOs and academic institutions. He writes Walker Jay's blog (http://walkerjay.wordpress.com ).

This article is published by N. Jayaram, and openDemocracy.net under a Creative Commons licence

Due to a recent spate of abusive, racist and xenophobic comments we are forced to revise our comment policy and has put all comments on moderation que.