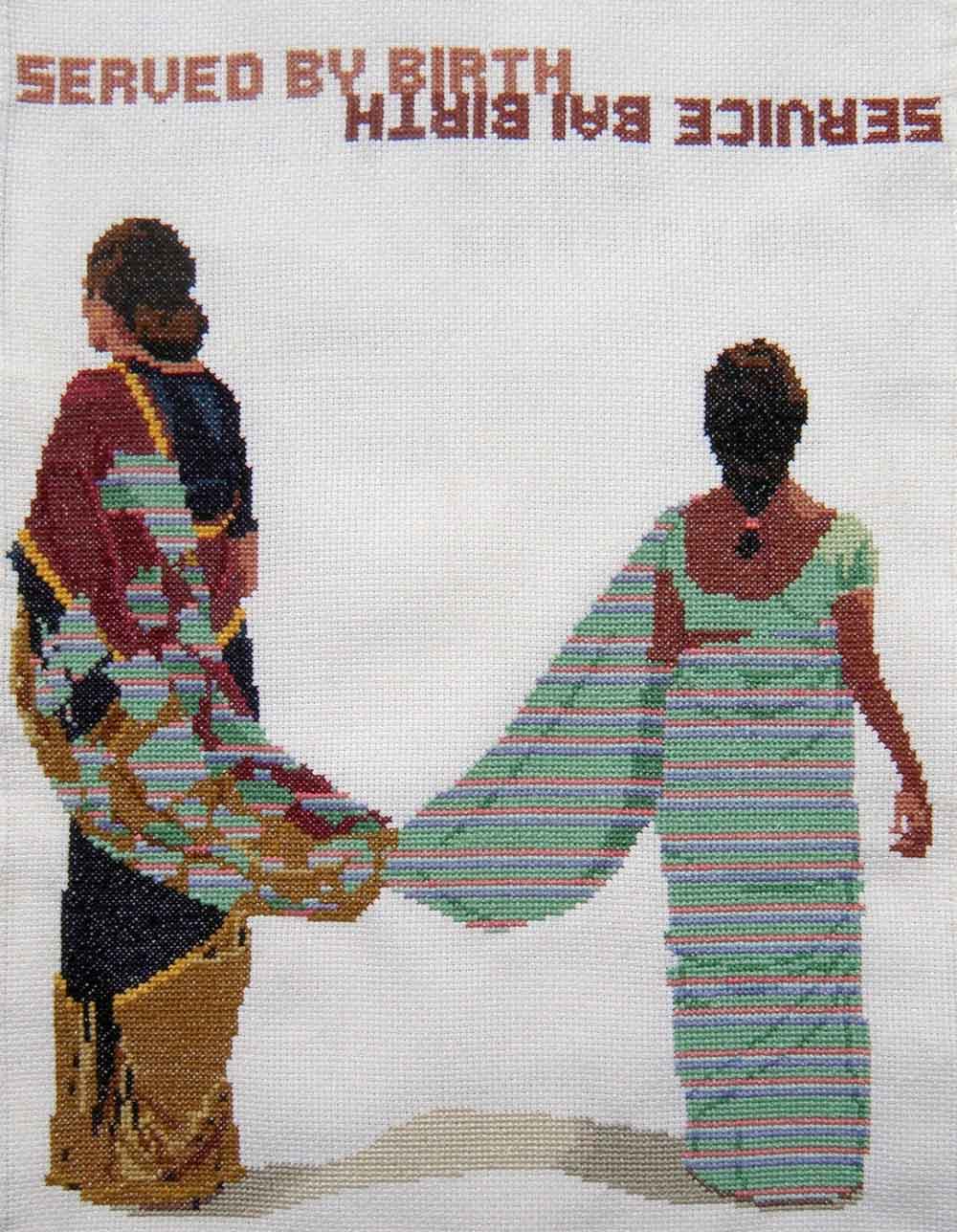

Served By Birth, Service Bai Birth

By Priti Gulati Cox

16 February, 2016

Countercurrents.org

Cross Stitch Embroidery, 2016

While I sip local Merlot with my maid-cooked eggplant parmesan made with Haiko (supermarket) shopped ingredients, she opens her purse. Breaking a small piece of tambakoo from its packet, she cups it in left palm and rubs it a little with her right thumb before planting it in her mouth, letting the tobacco mixture numb her aching senses. I sip to toast my lucky birth, whilst her lower lip swells to mourn it.

“My life has no meaning,” she says. I have heard that emotion expressed by many women across the caste spectrum in India, including those we refer to as Dalits, today (formerly known as untouchables/outcastes). The difference is in the context of jati (caste) and the source of subjugation. In other words, the “meaning” in her life bears weight depending on where in the jati ladder she was born.

The lower the social and economic rung, the heavier the weight, and the higher the economic and (most importantly, social independence) rung, the lighter the weight. According to the Forbes’ list, the top weightless, in-the-cloud six rungs are currently occupied by Kiran Mazumdar Shaw, Savitri Jindal, Indu Jain, Anu Aga, Shobhana Bhartia and Vidya Murkumbik— the six richest Indian women.

Speaking from the standpoint of someone like myself, an upper-caste employer, whose birth-right it is to sit back and be served, cannot possibly imagine what it must mean to be the person behind the birth-no-rights bai (maid) brown eyes that serve me. Listening to their life stories reinforces the huge imbalance of access to resources that govern our jati-bound disparate lives, and nothing else.

The one common suppressor that shapes most Indian women’s lives irrespective of their caste is patriarchy. A bai’s life also bears the burden of beginning in a birth-no-rights caste. So it’s a double whammy for her. When an upper-caste woman expresses a feeling of emptiness, it might be a consequence of the men in her life.

My mother once said to me, “Ye mard apne aap ko bahut ooncha samajhte hain. Auraton ki zindagi barbad kar di (These men think too much of themselves. They have ruined the lives of women.) And one upper-caste woman once told me that although she has all the comforts that money can buy her, she “lost out on love.” One category of Indian women wins some and loses some, while another category loses some and then loses some more.

Certain words apply solely to an upper-caste lexicon like the one I use. Take the word ‘splurge’ for instance. It goes with a certain lifestyle that include semi-conscious choices such as vegetarianism, urban vertical “farming”, supermarkets, window shopping, alphonso mangoes and Starbucks. All of these splurges have no place in the lives of our maids that clean and cook for us and that, in stark contrast, might plead with us one day to let them leave their jobs a little early so they can shop for a pair of chappals (slippers) to replace the ones that broke yesterday from jumping off the crowded local train to get to here.

Modern industry, resulting from the railway system, will dissolve the hereditary divisions of labor, upon which rest the Indian castes, those decisive impediments to Indian progress and Indian power—Karl Marx, The Future Results of British Rule in India, July 22, 1853.

Little did Marx know that the same wheels he thought could free her would one day deliver her two worn hands to an even more violent exploitation at the very doorsteps of a stagnant but still rapidly mutating Jatindia (a more appropriate name for the country of India.)

All of us women who have access to resources in our day-to-day lives, including loving husbands and independence, indulge in some form of waste in varying degrees and materiality. Only the indigenous folks who continue to inhabit this dying planet waste nothing. But we’re all too polluted now to learn anything from them, it seems. Some of us who share a certain worldview feel the need to pay for our sins, for instance, by taking a metaphorical dupki (dip) in the Ganges by recycling, consuming farm raised chicken, or buying carbon tradeoffs and so on.

Of course, we should recycle and eat local and all that feel-good stuff, but the world demands a lot more change in our lifestyles, along with soul-searching, direct action, taking to the streets, and holding our policymakers and their corporate bedfellas accountable. Short baby steps just ain’t gonna do it, unfortunately. Even our self-proclaimed, yoga-loving, spirituality-seeking feminists around the world fail to see the gaping hole in an understanding of the invisible hand of Brahmanism and its perpetual hold on the psyche of a Jatindia—a white hole that personifies a diseased popular culture that treats its women like shit to varying degrees.

The key distinction here is the ability to choose. I might choose to be a vegetarian so therefore I can be one. She wants to be able to pay for her son’s hotel management course that costs Rs. 100,000 ($ 1,468), but that’s way, way beyond her means. A large number of urban domestic maids end up caring for and financially supporting their children. Many of them will tell you that “I got married when I was very young. We had two children. Soon after that my husband left me for another woman. Now I have to single-handedly pay for my children’s food, education etc.”

There is numbing monotony in women’s lives in India, but the difference is in access to breaking that rhythm temporarily with economic freedom, or not. An employer sipping her morning tea, reading the Times of India and listening to a distant drum roll of the approaching train wheels delivering her other two hands and feet in brand new chappals, with the same old greeting, “Namaste, Madam.” Another shopping list, another swollen lower lip, another day with no meaning.

Their lives are intertwined in thought, paloo (the part of a sari that drapes over the shoulder), and shadow. Only one’s economic-freedom paloo is patchworked with another’s lack of such freedom.Their interdependence is invisible to the naked eye.

Priti Gulati Cox is an interdisciplinary artist. She lives in Salina, Kansas, and can be reached at: [email protected].