Targeting Civilians: The Erosion Of Ethical Principles During World War II

By John Scales Avery

01 September, 2012

Countercurrents.org

When Hitler invaded Poland in September, 1939, US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appealed to Great Britain, France, and Germany to spare innocent civilians from terror bombing. “The ruthless bombing from the air of civilians in unfortified centers of population during the course of the hostilities”, Roosevelt said (referring to the use of air bombardment during World War I) “..has sickened the hearts of every civilized man and woman, and has profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity.” He urged “every Government which may be engaged in hostilities publicly to affirm its determination that its armed forces shall in no event, and under no circumstances, undertake the bombardment from the air of civilian populations or of unfortified cities.”

Two weeks later, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain responded to Roosevelt's appeal with the words: “Whatever the lengths to which others may go, His Majesty's Government will never resort to the deliberate attack on women and children and other civilians for purposes of mere terrorism.”

Much was destroyed during World War II, and among the casualties of the war were the ethical principles that Roosevelt and Chamberlain announced at its outset. At the time of Roosevelt and Chamberlain's declarations, terror bombing of civilians had already begun in the Far East. On 22 and 23 September, 1937, Japanese bombers attacked civilian populations in Nanjing and Canton. The attacks provoked widespread protests. The British Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Cranborne, wrote: “Words cannot express the feelings of profound horror with which the news of these raids has been received by the whole civilized world. They are often directed against places far from the actual area of hostilities. The military objective, where it exists, seems to take a completely second place. The main object seems to be to inspire terror by the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians...”

On the 25th of September, 1939, Hitler's air force began a series of intense attacks on Warsaw. Civilian areas of the city, hospitals marked with the Red Cross symbol, and fleeing refugees all were targeted in a effort to force the surrender of the city through terror. On the 14th of May, 1940, Rotterdam was also devastated. Between the 7th of September 1940 and the 10th of May 1941, the German Luftwaffe carried out massive air attacks on targets in Britain. By May, 1941, 43,000 British civilians were killed and more than a million houses destroyed.

Although they were not the first to start it, by the end of the war the United States and Great Britain were bombing of civilians on a far greater scale than Japan and Germany had ever done. For example, on July 24-28, 1943, British and American bombers attacked Hamburg with an enormous incendiary raid whose official intention "the total destruction" of the city.

The result was a firestorm that did, if fact, lead to the total destruction of the city. One airman recalled, that “As far as I could see was one mass of fire. 'A sea of flame' has been the description, and that's an understatement. It was so bright that I could read the target maps and adjust the bomb-sight.” Another pilot was “...amazed at the awe-inspiring sight of the target area. It seemed as though the whole of Hamburg was on fire from one end to the other and a huge column of smoke was towering well above us - and we were on 20,000 feet! It all seemed almost incredible and, when I realized that I was looking at a city with a population of two millions, or about that, it became almost frightening to think of what must be going on down there in Hamburg.”

Below, in the burning city, temperatures reached 1400 degrees Fahrenheit, a temperature at which lead and aluminum have long since liquified. Powerful winds sucked new air into the firestorm. There were reports of babies being torn by the high winds from their mothers' arms and sucked into the flames. Of the 45,000 people killed, it has been estimated that 50 percent were women and children and many of the men killed were elderly, above military age. For weeks after the raids, survivors were plagued by “...droves of vicious rats, grown strong by feeding on the corpses that were left unburied within the rubble as well as the potatoes and other food supplies lost beneath the broken buildings.”

The German cities Kassel, Pforzheim, Mainz, Dresdin and Berlin were similarly destroyed, and in Japan, US bombing created firestorms in many cities, for example Tokyo, Kobe and Yokahama. In Tokyo alone, incendiary bombing caused more than 100,000 civilian casualties.

The nuclear arms race

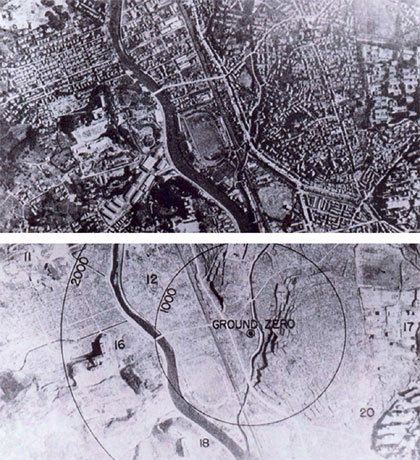

On August 6, 1945, at 8.15 in the morning, a nuclear fission bomb was exploded in the air over the civilian population of Hiroshima in an already virtually defeated Japan. The force of the explosion was equivalent to fifteen thousand tons of TNT. Out of a city of two hundred and fifty thousand, one hundred thousand were killed immediately, and another hundred thousand were hurt. Many of the injured died later from radiation sickness. A few days later, Nagasaki was similarly destroyed.

On August 6, 1945, at 8.15 in the morning, a nuclear fission bomb was exploded in the air over the civilian population of Hiroshima in an already virtually defeated Japan. The force of the explosion was equivalent to fifteen thousand tons of TNT. Out of a city of two hundred and fifty thousand, one hundred thousand were killed immediately, and another hundred thousand were hurt. Many of the injured died later from radiation sickness. A few days later, Nagasaki was similarly destroyed.

The tragic destruction of the two Japanese cities was horrible enough in itself, but it also marked the start of a nuclear arms race that continues to cast a very dark shadow over the future of civilization. Not long afterwards, the Soviet Union exploded its own atomic bomb, creating feelings of panic in the United States. President Truman authorized an all-out effort to build superbombs based on thermonuclear reactions, the reactions that heat the sun and stars.

In March, 1954, the US tested a thermonuclear bomb at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. It was 1000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb. The Japanese fishing boat, Lucky Dragon, was 135 kilometers from the Bikini explosion, but radioactive fallout from the explosion killed one crew member and made all the others seriously ill. The distance to the Marshall Islands was equally large, but even today, islanders continue to suffer from the effects of fallout from the test, for example frequent birth defects.

Driven by the paranoia of the Cold War, the number of nuclear weapons on both sides reached truly insane heights. At the worst point, there were 50,000 nuclear weapons in the world, with a total explosive power roughly a million times the power of the Hiroshima bomb. This was equivalent to 4 tons of TNT for every person on the planet, enough to destroy human civilization many times over, enough to threaten the existence of all life on earth.

At the end of the Cold War, most people heaved a sigh of relief and pushed the problem of nuclear weapons away from their minds. It was a threat to life too horrible to think about. People felt that they could do nothing in any case, and they hoped that the problem had finally disappeared.

Today, however, many thoughtful people realize that the problem of nuclear weapons has by no means disappeared, and in some ways it is even more serious now than it was during the Cold War. There are still 20,000 nuclear weapons in the world, many of them hydrogen bombs, many on hair-trigger alert, ready to be fired with only a few minutes warning. The world has frequently come extremely close to accidental nuclear war. If nuclear weapons are allowed to exist for a long period of time, the probability for such a catastrophic accident to happen will grow into a certainty.

Current dangers also come from proliferation. Recently, more and more nations have come to possess nuclear weapons, and thus the danger that they will be used increases. For example, if Pakistan's less-than-stable government should fall, its nuclear weapons might find their way into the hands of terrorists, and against terrorism deterrence has no effect.

Thus we live at a special time in history, a time of crisis for civilization. We did not ask to be born at a moment of crisis, but such is our fate. Every person now alive has a special responsibility: We owe it, both to our ancestors and to future generations, to build a stable and cooperative future world. It must be a war-free world, from which nuclear weapons have been completely abolished. No person can achieve these changes alone, but together we can build the world that we desire. This will not happen through inaction, but it can happen through the dedicated work of large numbers of citizens.

Civilians have for too long played the role of passive targets, hostages in the power struggles of politicians. It is time for civil society to make its will felt. If our leaders continue to enthusiastically support the institution of war, if they will not abolish nuclear weapons, then let us have new leaders.

John Avery received a B.Sc. in theoretical physics from MIT and an M.Sc. from the University of Chicago. He later studied theoretical chemistry at the University of London, and was awarded a Ph.D. there in 1965. He is now Lektor Emeritus, Associate Professor, at the Department of Chemistry, University of Copenhagen. Fellowships, memberships in societies: Since 1990 he has been the Contact Person in Denmark for Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs. In 1995, this group received the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts. He was the Member of the Danish Peace Commission of 1998. Technical Advisor, World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe (1988- 1997). Chairman of the Danish Peace Academy, April 2004. http://www.fredsakademiet.dk/ordbog/aord/a220.htm

John Avery received a B.Sc. in theoretical physics from MIT and an M.Sc. from the University of Chicago. He later studied theoretical chemistry at the University of London, and was awarded a Ph.D. there in 1965. He is now Lektor Emeritus, Associate Professor, at the Department of Chemistry, University of Copenhagen. Fellowships, memberships in societies: Since 1990 he has been the Contact Person in Denmark for Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs. In 1995, this group received the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts. He was the Member of the Danish Peace Commission of 1998. Technical Advisor, World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe (1988- 1997). Chairman of the Danish Peace Academy, April 2004. http://www.fredsakademiet.dk/ordbog/aord/a220.htm

Comments are moderated