Food security As If WomenMattered (Part II):

Why And How It Works In Kerala

By Ananya Mukherjee-Reed

01 November, 2010

One World South Asia

Part I of this article took us to a journey through Kerala where women are engaged to ensure food security though their group Kudumbashree. The concluding part throws light on its organisational structure , the systematic linkages it has established with administrative surroundings and how it has empowered the local women. The author asks, "As warnings about the impending food crisis pour in, are there lessons that could be learnt from Kudumbashree’s women-led approach to food security"?

Last week, I began a story about Kudumbashree, a network of 3.7 million women in Kerala. Some 250,000 Kudumbashree members are currently experimenting with an innovative food security strategy. The core of the strategy, as defined in the Kerala’s Food Security Action Plan, involves increasing the production of food in the state. Also a critical thrust of the strategy is to increase women’s participation in agriculture, particularly in the production of food. Both these elements – the focus on food production and the involvement of women – are conspicuously absent from most food security strategies today, including the one adopted by the Government of India. The discourse remains narrowly focused on the question of distribution of food, that too via ill-conceived targeting strategies, while any serious examination of the conditions of food production remains absent.

Click here to see presentation.

Currently, around 250,000 women are

practising collective farming on about

66,000 acres of land

Against this canvas, how are we to understand the potential of Kudumbashree’s food security experiment? As a follow-up to Part I, I highlight below three key dimensions: the sense of ownership that women display in relation to their farm work; the organisational structure of the collective farming experiment; and the systematic links between the local government and the community on which the experiment rests.

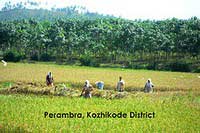

Currently, around 250,000 women are practising collective farming in an approximate area of 27000 hectares (66,000 acres). Such a scale of women’s involvement in collective production is certainly not common.Kudumbashree farmers show great enthusiasm for further expanding these operations. They are eager to experiment with new crops, organic methods, better governance, stronger connections to their local markets and so on.Where does this enthusiasm come from?

First, farming, as the women tell me, comes naturally to them. For some, this is their first opportunity to use their ‘natural’ skills towards an independent income. For others, collective farming marks a highly significant transition from wage labour to independent production. Women eagerly speak of the control over their time and labour that they now enjoy and that they never had before. Second, their enthusiasm for farm work has much to do with the collective nature of the activity and the relations of solidarity. As a Kudumbashree farmer in Kozhikode told me, "We have developed so much solidarity I feel we can do almost anything."

As indicated by these words of a young Muslim woman, Kudumbashree groups seem to demonstrate a strong sense of social inclusion. Members are vocal against caste and religious discrimination. They proudly proclaim Kudumbashree to be first and foremost as an organisation of poor women. While it is hard to assess how representative this is of Kudumbashree’s 3.7 million members, I do wonder what makes such social inclusion possible, especially given the deeply divisive nature of the Indian society. My hypothesis is that the fabric which connects Kudumbashree members draws upon gender, class and locality and the commonality of experiences that derive from there. The women’s involvement in farming appears to provide a common experience where solidarity triumphs social schisms.

In order to better understand these social relations, we need to take a close look at how Kudumbashree is organised. Kudumbashree has a three-tiered structure, which begins from the neighbourhood group (NHG). Each comprising 10-20 women, the NHGs are led by elected representatives and have regular weekly meetings where women discuss issues related to their community. Often, a NHG is a woman’s first exposure outside the home. As I heard repeatedly from members, it is through this participation that she transforms from a quiet, neglected ‘housewife’ to a vocal member of the community. By and large, the members of the farming collectives are drawn from the NHGs. The existing relations of solidarity greatly enhance decision-making within the collective. For example, decisions as to how much of the collective’s surplus is to be sold, how much is to be consumed, which member needs more food support, how are profits to be deployed – are all informed by the relations of solidarity rather than just the ‘bottom line’.

All the NHGs in a single ward are federated into an Area Development Society (ADS), which are also governed by elected office-bearers who represent the NHGs. The ADSs are further federated at the level of the panchayat/municipality to form a Community Development Society (CDS). The CDS thus becomes ‘the representative structure of the vast network of NHGs in the Grama (village) Panchayat/Municipal areas. It works in close liaison with the local self government and serves as both, a dissemination organ for government programmes and an enunciator of community needs in governance issues’.

This dual role – of bringing government programmes and resources to the community and bringing community needs to the government, especially the local government - is a key feature of Kudumbashree It derives from Kudumbashree’s roots in the People’s Plan Campaign for decentralisation initiated by the Government of Kerala in 1996. The Campaign had two main features: to transfer a part of state finances to local governments which the latter could use for its development needs; and two, a massive effort to open up the planning process to community participation. These steps transformed decentralisation ‘from a mere administrative exercise into a mass movement’1. In 1998, Kudumbashree was launched to further popular participation in local development. The vision was for Kudumbashree to become ‘the community voice of local self-government - in particular the voice of the economically and socially weak, and of women’.

This history, and the deep state-community linkages that it has fostered, contradicts clearly the neo-liberal claim that development is best done by communities alone, and the state can only be a hindrance. The farming initiative amply demonstrates how a policy vision, when rooted in local realities, can come to be ‘owned’ by the people whose lives it affects. Neither individualistic anti-state models nor top-down ‘state-led’ models generate this sense of ownership. As I heard in almost every collective, while the idea of farming was floated at panchayat meetings and Kudumbashree Community Development Society meetings, they were never taken up without extensive discussions at the neighbourhood groups. The main production-related decisions are all taken by the farmers, with various kinds of support and incentives from public institutions.

What does all this tell us about food security policy? For one, food security entails a whole gamut of social relations. It is not something that can be determined solely by technocrats in isolation from these relations. This is why many social struggles reject the notion of food security altogether – and speak instead for food sovereignty. Food sovereignty strives for fundamental transformation in social relations governing the production and consumption of food.

Second, while Kudumbashree’s community structure provides an excellent basis for people-centered, inclusive food security practices, material constraints remain paramount. Land, for example, remains a central constraint. At present, Kudumbashree farmers do not own land, but lease it. They worry about the insecurity of their lease. What happens if the lease is revoked after they have put in the labour and investment to rejuvenate 100+acres fallow land? Obtaining finance also remains a challenge. While organic farming is their preferred method, the lack of availability of organic seeds and chemical-free inputs pose serious constraints. Interestingly, what they seem fairly confident about is the demand for their products, a confidence that is borne out by evidence. This demand derives from their reputation in local communities as well as the elaborate network of community markets that Kudumbashree has developed over the years.

Can this experiment be sustained and expanded? Only if the emphasis on the collective dimension and the state-community linkage remains. These dimensions distinguish Kudumbashree from Grameen-style microcredit, or individualistic income-generation programmes and brings it closer to the vision of producer sovereignty and empowerment that many social movements endorse.

Ananya Mukherjee-Reed is a professor of Political Science, Development Studies and Social and Political Thought at York University, Toronto, Canada.]

Ananya Mukherjee-Reed is a professor of Political Science, Development Studies and Social and Political Thought at York University, Toronto, Canada.]

Ramakumar R, Nair KN. 2009. State, politics and civil society: A note on the experience of Kerala. In: Geiser U, Rist S, editors. Decentralisation Meets Local Complexity: Local Struggles,State Decentralisation and Access to Natural Resources in South Asia and Latin America. Perspectives of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, University of Bern, Vol. 4. Bern: Geographica Bernensia, pp 275–310.