Galactic-Scale Energy

By Tom Murphy

19 July, 2011

Do The Math

This series takes an astrophysicist's-eye view of the predicament we face managing resource limitations, energy production, climate change, and economic growth. The approach is often playfully quantitative, with the aim of arriving at a fresh perspective on our world. Weekly articles stress estimation over exactness, because often a reasonably complete picture can be developed without lots of decimal places. Estimations of this type can be used to bring clarity to complex issues, or to evaluate the potential of proposed energy solutions. Hopefully, readers will gain the courage and techniques to start making valuable estimations of their own. The series starts out with a two-part assessment of the implications of continued growth, then settles down to tackle a variety of cute questions relating to energy storage, biofuels, home energy, transport, climate change, etc.

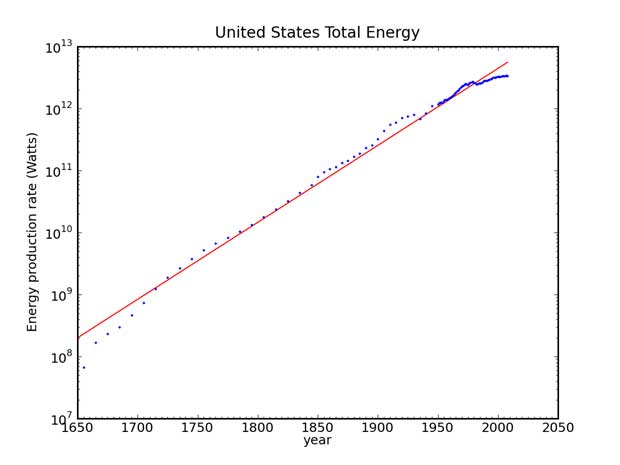

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, we have seen an impressive and sustained growth in the scale of energy consumption by human civilization. Plotting data from the Energy Information Agency on U.S. energy use since 1650 (1635-1945, 1949-2009, including wood, biomass, fossil fuels, hydro, nuclear, etc.) shows a remarkably steady growth trajectory, characterized by an annual growth rate of 2.9% (see figure). It is important to understand the future trajectory of energy growth because governments and organizations everywhere make assumptions based on the expectation that the growth trend will continue as it has for centuries—and a look at the figure suggests that this is a perfectly reasonable assumption.

Total U.S. Energy consumption in all forms since 1650. The vertical scale is logarithmic, so that an exponential curve resulting from a constant growth rate appears as a straight line. The red line corresponds to an annual growth rate of 2.9%. Data source: EIA.

Growth has become such a mainstay of our existence that we take its continuation as a given. Growth brings many positive benefits, such as cars, television, air travel, and iGadgets. Quality of life improves, health care improves, and, aside from a proliferation of passwords to remember, life tends to become more convenient over time. Growth also brings with it a promise of the future, giving reason to invest in future development in anticipation of a return on the investment. Growth is then the basis for interest rates, loans, and the finance industry.

Because growth has been with us for “countless” generations—meaning that everyone we ever met or our grandparents ever met has experienced it—growth is central to our narrative of who we are and what we do. We therefore have a difficult time imagining a different trajectory.

This post provides a striking example of the impossibility of continued growth at current rates—even within familiar timescales. For a matter of convenience, we lower the energy growth rate from 2.9% to 2.3% per year so that we see a factor of ten increase every 100 years. We start the clock today, with a global rate of energy use of 12 terawatts (meaning that the average world citizen has a 2,000 W share of the total pie). We will begin with semi-practical assessments, and then in stages let our imaginations run wild—even then finding that we hit limits sooner than we might think. I will admit from the start that the assumptions underlying this analysis are deeply flawed. But that becomes the whole point, in the end.

A Race to the Galaxy

I have always been impressed by the fact that as much solar energy reaches Earth in one hour as we consume in a year. What hope such a statement brings! But let’s not get carried away—yet.

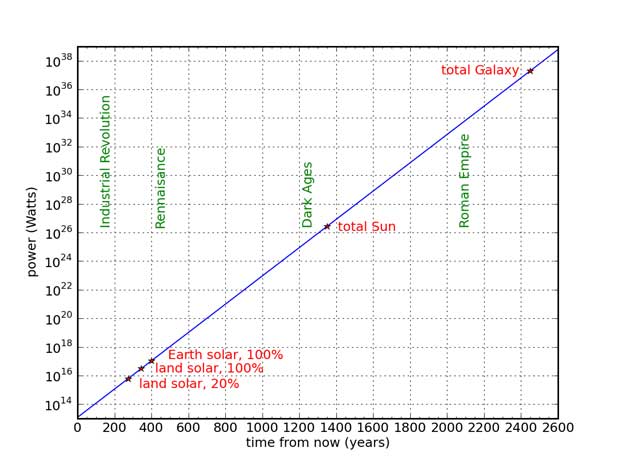

Only 70% of the incident sunlight enters the Earth’s energy budget—the rest immediately bounces off of clouds and atmosphere and land without being absorbed. Also, being land creatures, we might consider confining our solar panels to land, occupying 28% of the total globe. Finally, we note that solar photovoltaics and solar thermal plants tend to operate around 15% efficiency. Let’s assume 20% for this calculation. The net effect is about 7,000 TW, about 600 times our current use. Lots of headroom, yes?

When would we run into this limit at a 2.3% growth rate? Recall that we expand by a factor of ten every hundred years, so in 200 years, we operate at 100 times the current level, and we reach 7,000 TW in 275 years. 275 years may seem long on a single human timescale, but it really is not that long for a civilization. And think about the world we have just created: every square meter of land is covered in photovoltaic panels! Where do we grow food?

Now let’s start relaxing constraints. Surely in 275 years we will be smart enough to exceed 20% efficiency for such an important global resource. Let’s laugh in the face of thermodynamic limits and talk of 100% efficiency (yes, we have started the fantasy portion of this journey). This buys us a factor of five, or 70 years. But who needs the oceans? Let’s plaster them with 100% efficient solar panels as well. Another 55 years. In 400 years, we hit the solar wall at the Earth’s surface. This is significant, because biomass, wind, and hydroelectric generation derive from the sun’s radiation, and fossil fuels represent the Earth’s battery charged by solar energy over millions of years. Only nuclear, geothermal, and tidal processes do not come from sunlight—the latter two of which are inconsequential for this analysis, at a few terawatts apiece.

But the chief limitation in the preceding analysis is Earth’s surface area—pleasant as it is. We only gain 16 years by collecting the extra 30% of energy immediately bouncing away, so the great expense of placing an Earth-encircling photovoltaic array in space is surely not worth the effort. But why confine ourselves to the Earth, once in space? Let’s think big: surround the sun with solar panels. And while we’re at it, let’s again make them 100% efficient. Never-mind the fact that a 4 mm-thick structure surrounding the sun at the distance of Earth’s orbit would require one Earth’s worth of materials—and specialized materials at that. Doing so allows us to continue 2.3% annual energy growth for 1350 years from the present time.

At this point you may realize that our sun is not the only star in the galaxy. The Milky Way galaxy hosts about 100 billion stars. Lots of energy just spewing into space, there for the taking. Recall that each factor of ten takes us 100 years down the road. One-hundred billion is eleven factors of ten, so 1100 additional years. Thus in about 2500 years from now, we would be using a large galaxy’s worth of energy. We know in some detail what humans were doing 2500 years ago. I think I can safely say that I know what we won’t be doing 2500 years hence.

Global power demand under sustained 2.3% growth on a logarithmic plot. In 275, 345, and 400 years, we demand all the sunlight hitting land and then the earth as a whole, assuming 20%, 100%, and 100% conversion efficiencies, respectively. In 1350 years, we use as much power as the sun generates. In 2450 years, we use as much as all hundred-billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy. Vertical notes provide historical perspective on how distant these benchmarks are in the context of civilization.

Why Single Out Solar?

Some readers may be bothered by the foregoing focus on solar/stellar energy. If we’re dreaming big, let’s forget the wimpy solar energy constraints and adopt fusion. The abundance of deuterium in ordinary water would allow us to have a seemingly inexhaustible source of energy right here on Earth. We won’t go into a detailed analysis of this path, because we don’t have to. The merciless growth illustrated above means that in 1400 years from now, any source of energy we harness would have to outshine the sun.

Let me restate that important point. No matter what the technology, a sustained 2.3% energy growth rate would require us to produce as much energy as the entire sun within 1400 years. A word of warning: that power plant is going to run a little warm. Thermodynamics require that if we generated sun-comparable power on Earth, the surface of the Earth—being smaller than that of the sun—would have to be hotter than the surface of the sun!

Thermodynamic Limits

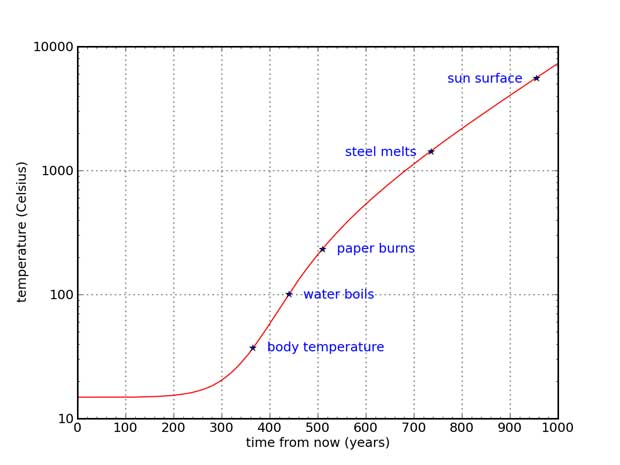

We can explore more exactly the thermodynamic limits to the problem. Earth absorbs abundant energy from the sun—far in excess of our current societal enterprise. The Earth gets rid of its energy by radiating into space, mostly at infrared wavelengths. No other paths are available for heat disposal. The absorption and emission are in near-perfect balance, in fact. If they were not, Earth would slowly heat up or cool down. Indeed, we have diminished the ability of infrared radiation to escape, leading to global warming. Even so, we are still in balance to within less than the 1% level. Because radiated power scales as the fourth power of temperature (when expressed in absolute terms, like Kelvin), we can compute the equilibrium temperature of Earth’s surface given additional loading from societal enterprise.

Earth surface temperature given steady 2.3% energy growth, assuming some source other than sunlight is employed to provide our energy needs and that its use transpires on the surface of the planet. Even a dream source like fusion makes for unbearable conditions in a few hundred years if growth continues. Note that the vertical scale is logarithmic.

The result is shown above. From before, we know that if we confine ourselves to the Earth’s surface, we exhaust solar potential in 400 years. In order to continue energy growth beyond this time, we would need to abandon renewables—virtually all of which derive from the sun—for nuclear fission/fusion. But the thermodynamic analysis says we’re toasted anyway.

Stop the Madness!

The purpose of this exploration is to point out the absurdity that results from the assumption that we can continue growing our use of energy—even if doing so more modestly than the last 350 years have seen. This analysis is an easy target for criticism, given the tunnel-vision of its premise. I would enjoy shredding it myself. Chiefly, continued energy growth will likely be unnecessary if the human population stabilizes. At least the 2.9% energy growth rate we have experienced should ease off as the world saturates with people. But let’s not overlook the key point: continued growth in energy use becomes physically impossible within conceivable timeframes. The foregoing analysis offers a cute way to demonstrate this point. I have found it to be a compelling argument that snaps people into appreciating the genuine limits to indefinite growth.

Once we appreciate that physical growth must one day cease (or reverse), we can come to realize that all economic growth must similarly end. This last point may be hard to swallow, given our ability to innovate, improve efficiency, etc. But this topic will be put off for another post.

Acknowledgments

I thank Kim Griest for comments and for seeding the idea that in 2500 years, we use up the Milky Way galaxy, and I thank Brian Pierini for useful comments.

Editorial Notes

Tom Murphy is an associate professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego. An amateur astronomer in high school, physics major at Georgia Tech, and PhD student in physics at Caltech, Murphy has spent decades reveling in the study of astrophysics. He currently leads a project to test General Relativity by bouncing laser pulses off of the reflectors left on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts, achieving one-millimeter range precision. Murphy’s keen interest in energy topics began with his teaching a course on energy and the environment for non-science majors at UCSD. Motivated by the unprecedented challenges we face, he has applied his instrumentation skills to exploring alternative energy and associated measurement schemes. Following his natural instincts to educate, Murphy is eager to get people thinking about the quantitatively convincing case that our pursuit of an ever-bigger scale of life faces gigantic challenges and carries significant risks.

Comments are not moderated. Please be responsible and civil in your postings and stay within the topic discussed in the article too. If you find inappropriate comments, just Flag (Report) them and they will move into moderation que.