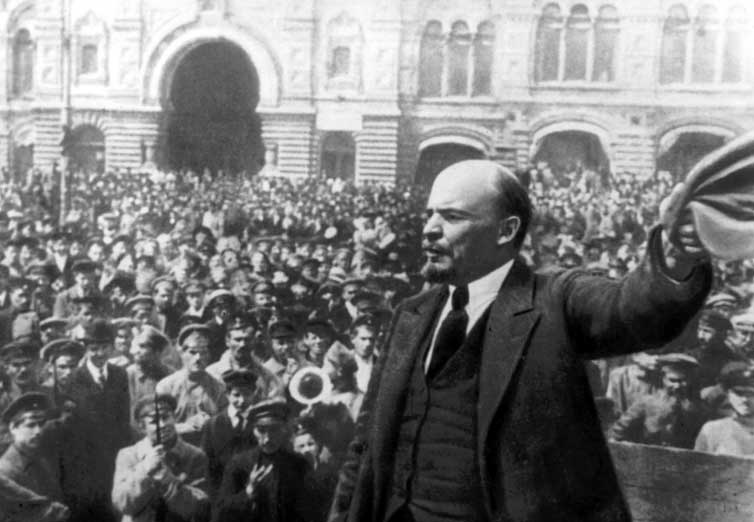

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov - Lenin, The Maker Of The Russian Revolution

By Gaither Stewart

25 April, 2016

Countercurrents.org

PART 1: Lenin on Compromises

In Lenin’s “Left-wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder”, written in 1920 as a polemic against Dutch and British groups in the new Third International meeting that year in its Second Congress in which strategy and tactics were debated. His target was the West European ultra-left communists who had come out against Marxists working in trade unions or running for public office and sitting in bourgeois parliaments

In his polemic against them Lenin says “it is sad to see people who doubtless consider themselves Marxists forgetting the fundamental truths of Marxism.” As Lenin often did, to make his point he cited the brilliant Engels’ article on the Blanquist Communards who aimed at achieving their aims without any intermediate stations, i.e. without any compromises, which they saw as mere obstacles postponing victory and prolonging the period of slavery to the capitalist class.

Lenin pointed out that the successes of the body of German communists were due to their acceptance of the compromises dictated by historical development while they “constantly pursue the final aim, the abolition of classes and the creation of a society in which there will no longer be private ownership of land or the means of production.” He criticized the Blanquards for wanting to skip intermediate phases and compromises.

“What childish innocence it is to present impatience as a theoretically convincing argument!”

Lenin notes that to young and inexperienced revolutionaries as well as petty-bourgeois revolutionaries it seemed incorrect to “allow compromises”; then he cites British opportunists who reason that “if the Bolsheviks may make a certain compromise, why may we not make any kind of compromises.” From those two positions he shows that there are compromises and there are compromises. “Every proletarian has been through strikes and has experienced compromises when workers had to go back to work either without having achieved anything or agreeing to only partial satisfaction of their demands. The proletarian notices the difference between a compromise enforced by objective conditions such as lack of strike funds and no outside support, extreme hunger and exhaustion which in no way reduces his revolutionary devotion and readiness to continue the struggle and a compromise by traitors like strikebreakers who because of cowardice toady to the capitalists and yield to intimidation, persuasion or flattery.”

In these days of critical issues and spinning disasters, it is not unusual to find competing groups and interests apparently sharing the same concerns or desired outcomes. There are “marriages of convenience” where the old “Enemy of my enemy is my friend” seems to be the preferred strategy. I believe that Lenin’s discussion here cautions against this type of compromise. Certainly there are those situations where different groups come together (and indeed must come together) to address a common problem, and compromises often come into play. In such situations it is critical to remember what is not negotiable: basic needs and deeply held principles. All too often this is forgotten and the inevitable ensuing power struggle ultimately determines the shape, context, and implementation of the “compromise,” which makes it no compromise at all. Compromises can be slippery slopes, for each compromise becomes the starting point for future negotiations and compromises. While I am not arguing that we need to be dogged ideologues, I am arguing that close held principles and visions should not be on the compromise chopping block – not for any party to the negotiations.

In politics however it is a more decision than is differentiating between legitimate compromise in a strike and the traitorous strikebreaker. That, Lenin repeats as he so often does, is the task of party organization and party leaders who through long experience acquire the knowledge and also instinct to resolve political problems, like identifying the mutable dividing line between what is legitimate compromise and what is opportunism. A long process of education, training, enlightenment and everyday experience is required to single out in each separate historical moment the impermissible and opportunistic compromises.

Here, Lenin dwells on the impermissible compromise of opportunism in “defence of the fatherland” when in WWI German socialists backed the predatory interests of its own bourgeoisie in the war, the defence of the bourgeois’s own country also against the revolutionary proletariat and the Soviet movement in Russia. That is, proletarian against proletarian, worker against worker. Lenin saw the defence of bourgeois democracy and parliamentarianism as the chief manifestation of impermissible compromises that he said the “sum total of which constituted the opportunism that is fatal to the revolutionary proletariat and its cause.”

Lenin then condemned certain German Lefts’ rejection of all compromises with other parties. Such views actually condemn the whole of Bolshevism, he points out, which in order to gain power, maneuvered, temporized and compromised with other parties, bourgeois parties included. “To refuse to maneuver, to utilize the conflict of interests among one’s enemies… is this not ridiculous in the extreme?”

After a Socialist revolution of the proletariat in one country, the proletariat of that country is still weaker than the bourgeoisie because of the latter’s international connections and the continuous restoration of capitalism by small commodity producers of the country that has overthrown the bourgeoisie. Compromises with mass allies are necessary.

“Capitalism would not be capitalism if the proletariat were not divided into more developed and less developed strata …, by territorial origin, trade, … religion, and so on. From this follows the absolute necessity for the vanguard of the proletariat, for its class-conscious section, for the Communist Party, to resort to maneuvers, arrangement and compromises with the various groups of proletarians, with the various parties of proletarians … and workers and small masters.

“The whole point,” Lenin concludes, “lies in knowing how to apply these tactics in order to raise the general level of proletarian class consciousness, revolutionary spirit, and ability to fight and win…”

PART 2: Lenin on Tactics of the Democratic Revolution

What state of history are we really in? For revolutionists the question is far from academic.

In his work “Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution”, Lenin discusses a vexing Russian pre-revolutionary problem similar to the problem facing American left radicals today. For Russia of that epoch the question was one of timing and tactics: Was the classical Marxian bourgeois revolution leading to a democratic republic as a first step toward the Socialist Revolution necessary, and even possible, considering the pusillanimous nature of the Russian bourgeoisie at the time? Or could Russia bypass bourgeois capitalism altogether and leap directly from backwardness into advanced socialism? Today, more than a handful of people ask: What will be the nature of the long overdue Great American Revolution?

Since the USA and the West are already in well-advanced capitalism, (albeit within only formally democratic republics—meaning democracies only in form but without substance) the second alternative seems to concern us more today. But is that true? A look at the historical circumstances of Lenin’s era from our historical point of view can be useful in determining where we really stand today.

In the section of his above work dedicated to the bourgeois revolution as “in the highest degree advantageous to the proletariat,” Lenin finds this to be true and in fact “absolutely necessary” in the interests of the proletariat. Today we should keep in mind that the proletariat in the USA is not only the former working class (despite the old-fashioned sound of the word “proletariat” to many, especially to the conservative, neocon imperialistic 0.01 percent), the size of the proletariat has not diminished as it might seem but has grown with the addition of a great part of the former middle class; in fact, around the corner waiting is a whole world consisting of a huge majority of proletarians ruled by a small elite

Lenin writes that it is more advantageous for the working class if the necessary social changes occur by way of revolution rather that by reform. That simple affirmation gives much room for thought! Reform, Lenin reminds is, is the route of “delay, procrastination and slow decomposition of the putrid parts of the national organism.” Moreover, as we see from day to day, in America as well as across Europe, the proletariat, the working man (1) and the impoverished former middle class—not to mention the poor and neglected one hundred million people of the USA, deprived of adequate health care and education, plagued by obesity and encouraged ignorance, and misled by constant and ubiquitous brainwash and false nationalist propaganda—could only benefit from the Marxist-Leninist, first phase bourgeois revolution before the determinant Great American Socialist Revolution being debated among America’s potential revolutionaries.(Unfortunately, apparently not among the masses of the brainwashed people, about which however I am inclined to think things are not exactly as we think they are.)

Contrary to appearances, today’s proletariat has grown with the addition of a great part of the former middle class. The inexorable dynamics of capitalism, always conducive to greater and more intractable inequality, are rapidly destroying this bulwark of the “American Dream.”

In any case, Lenin writes the revolutionary way is the shortcut to a “quick amputation, which is the least painful to the proletariat (which I hope we have agreed exists and is growing rapidly), the way of the direct removal of the decomposing parts, the way of fewest concessions to …(their) disgusting, vile, rotten, and contaminating institutions….” Marxism, Lenin recalls, urges the proletariat not to be aloof to the bourgeois revolution, but to take an energetic part in it and not to allow the bourgeoisie to take command of it.

On the other hand, Lenin advises against fears of a complete victory for social democracy in a democratic revolution and of a revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat… for such a victory would arouse the socialist proletariat of Europe… which would in turn help us (the USA likewise today!) to accomplish the socialist revolution.”

In this same article Lenin goes on to discuss the cardinal question of the “possibility of holding power” against the forces of counterrevolution against which maximum unity is necessary among all revolutionary forces. At this point, the path of the revolution lies not from oppression by autocracy in Russia or our 0.01 per cent today, but from a bourgeois republic to socialism.

Lenin hammers home his message that the “social democrat (in those times the future Bolshevik) must never for a moment forget that the proletariat will inevitably have to wage the class struggle for socialism (also) against the most democratic and republican bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie. Hence the absolute necessity of a separate, independent, strictly Class Party of Social Democracy (i.e., communism). Hence the temporary nature of out tactics of ‘striking jointly’ with the bourgeoisie and the duty of keeping strict watch ‘over our ally, as over an enemy.’”

Lenin intends that the fight against the autocracy (0.01 percent) is a temporary and transient task of the socialists, the negligence of which would be tantamount to betrayal of socialism and of serving reaction. The bourgeoisie “is inconsistent, self-seeking, and cowardly in its support of the revolution and will turn against the people as soon as its selfish interests are met. There remains the “people”, the proletariat and in those times the peasantry, in our epoch the blue collar workers, service workers, and impoverished middle class, etc., to march to the end, i.e. the socialist revolution.

“The Russian (read also, the American) Revolution will begin to assume its real sweep, will assume the widest revolutionary sweep possible … only when the bourgeoisie recoils from it and when the masses come out as active revolutionaries side by side with the proletariat. In order that our revolution may be carried to its conclusion, (we) must rely on such forces as are capable of paralyzing the inevitable inconsistency of the bourgeoisie, i.e. recoiling from the revolution….

“The proletariat (workers and former middle class) must accomplish the socialist revolution by allying itself to the mass of the semiproletarian elements of the population, in order to crush by force the bourgeoisie….

PART 3: LENIN AND THE WORKING CLASS AS THE VANUARD FOR SOCIAL DEMOCRACY

Above all, due to the grave obstacles it must overcome, the party of the working class must be a party of disciplined, professional revolutionaries…nothing short of this can succeed in acquiring and defending people’s power…

In 1902, Lenin published his long pamphlet What Is To Be Done, his first systematic development of his views on the nature of the revolutionary party. That writing is widely regarded today as one of the most influential political documents of the twentieth century. The following is a look at the main ideas contained in this famous pamphlet, published in Irving Howe’s collection of writings on socialism/communism. I am obliged to remind readers that in Lenin’s time of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the words “social democracy” corresponded to what became socialism/communism.

Lenin begins this section of What Is To Be Done with the statement that on the grounds of the pressing needs of the working class for political knowledge and political training, “the organization of wide political agitation and consequently of all-sided political exposures are an absolutely necessary and paramount task of activity, if that activity is to be truly social democratic.” (Bold italics ours).

But, as was Lenin’s dialectic style, he immediately adds that this kind of organization is insufficient in that it ignores the general tasks of social democracy as a whole. First, he approaches the subject from what he calls the “economist or practical” aspect. “Everyone agrees that it is necessary to develop the political consciousness of the working class,” he writes, before posing the question as to how that is to be accomplished? Seen only from the economic point of view, workers are concerned merely with the economic relations between the government and the working class, devoid of a political character. Therefore, he says, if we confine ourselves to the economic struggle, we will never develop the political consciousness of the workers.

An encyclopedic reader, and disciplined thinker who strove for grounding everything in the ultimate, incontrovertible reality of events, Lenin’ss insights into the nature of the bourgeois state have not lost their power to explain contemporary developments.

“The workers,” he continues, “can acquire political consciousness only from outside the sphere of worker-employers relations. The sphere from which it is possible to obtain this (political) knowledge is the sphere between all classes and the state—the sphere of interrelations between all classes. Therefore, the way for workers to acquire political knowledge is for social democrats “to go among all classes of the population, and dispatch units of their army in all directions.”

________________________________________

Lenin explains that he expresses himself in this awkward way in order to “stimulate the economists to take up their tasks which they unpardonably ignore, to make them understand the difference between trade unionism and social democratic politics, which they refuse to understand.” The type of social democratic circles of the period, he charges, was content with its “contact with the workers” and issuing leaflets about abuses in the factories, government partiality toward capitalists, and the tyranny of the police. Their group discussions reach no farther. No talk about the history of the revolutionary movement or questions of home and foreign policy of the government or the economic evolution of Russia and Europe or the positions of the various classes in society. No one dreams, Lenin remarks, of extending contacts with other classes of society. The leader of such circles is more like a trade union leader than a socialist political leader.

“It cannot be too strongly insisted that this is not enough to constitute social democracy.…The social democrat’s ideal (leader) should not be a trade union secretary, but a tribune of the people, able to react to every manifestation of tyranny and oppression, no matter where it takes place, no matter what stratum or class of the people it affects; he must be able to group all these manifestions into a single picture of police violence and capitalist exploitation; he must be able to take advantage of every petty event in order to explain …his social democratic demands to all, in order to explain to everyone the world historical significance of the struggle for the emancipation of the proletariat.”

Before continuing with Lenin and What Is To Be Done, I have to mention my own reactions at this point: it seems we are speaking also of America and Europe, of applying a historical situation to our own contemporary situation. And I must remind readers that the Leninist category “proletariat” is alive today and in the USA includes both the diminishing workers class and the rapidly growing and ever poorer former affluent middle class, so that Lenin’s encouragement to reach out to all classes rings super modern.

At the point we left off, Lenin asserts the following five points concerning the heart of Leninism:

1. no movement can be durable without a stable organization of leaders to maintain continuity;

2. the more widely the masses are drawn into the struggle and form the basis of the movement, the more necessary is it to have such an organization and the more stable must it be…;

3. the organization must consist chiefly of persons engaged in revolution as a profession;

4. in a country with a despotic government, the more we restrict the membership of this organization to persons who are engaged in revolution as a profession and who have been professionally trained in the art of combating the political police, the more difficult it will be to catch the organization;

5. and the wider will be the circle of men and women of the working class or of other classes of society able to join the movement and perform active work ….

At this point, Lenin raises the question whether it is possible to have a mass organization when strict secrecy is essential? He agrees that we can never guarantee the degree of secrecy required but he believes that the concentration of secret functions in the hands of a small number of professional revolutionaries does not mean that they will think for all and that the masses will have no active part in the movement. On the contrary, Lenin affirms optimistically, more and more professional revolutionaries should emerge from the masses … after years of training and experience. Lenin speaks of the reading and dissemination of “illegal literature” that will not diminish because a dozen professional revolutionaries concentrate the secret work in their hand, but it will increase tenfold. On the contrary, Lenin believed, the professional revolutionaries will be no less trained than the police. They will see to organizational matters like the construction of the organization territorially, appointing leaders in districts and towns and factories and institutions, at the same time expanding contacts with other organization such as trade unions, workers circles and circles for the whole population.

“We must have as large a number possible of such (associated) organizations having the widest possible variety of functions, but it is absurd and dangerous to confuse these with organizations of revolutionists, to erase the line of demarcation between them, to dim still more the already hazy appreciation by the masses that to serve the mass movement we must have people who will devote themselves exclusively to social-democratic activities, and that others must train themselves … to become professional revolutionaries….

________________________________________

In this short section of his famous work, Lenin lays out clearly and lucidly his revolutionary tactics for the execution of one of history’s greatest revolutions, which had worldwide effects comparable to those of the Great French Revolution a century and a half earlier. In sum, Lenin visualized a workers vanguard led by a small group of professional revolutionaries who dedicated their lives to overthrowing an oppressive state and its ideology by use of and collaboration with the many diverse classes of society and instituting a new classless order. Because of his early death at age 54 we cannot know, we can only speculate as to what kind of a state leader Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov, or Lenin, would have become. I personally have come to believe that whatever the circumstances of the succession to Lenin, Stalin did become the right leader for a Russia riddled by civil war, political divisions and anarchy, foreign interventions, an ignorant population, poverty, a nascent industry at a standstill and agriculture in chaos, and the hostility of the surrounding capitalist world with Socialist Russia in their sights. Though the power of the contemporary capitalist state might penetrate deeper into society and into the mentality of the population than in Lenin’s time via cradle to the grave brainwash, also modern technology offers much to the opposition to capitalist hegemony, both nationally and internationally.

PART 4: Lenin on Imperialism and Capitalism

First published in 1917, Lenin’s “Imperialism. The Highest Stage of Capitalism”, his major theoretical work, shows imperialism as a “direct continuation of the fundamental properties of capitalism,” a primary manifestation of capitalism in its late stages.

________________________________________

Returning to Lenin’s definition, we may add that imperialism reflects the same crisis of capitalism, in which it finds itself today: Lenin insists on the significance of the competition among capitalist nations, one against the other, (in a way foreseeing World Wars I and II), while capitalism itself schemes to meet the continuing and the growing demand for new sources of raw materials, new markets, cheap labor, and new avenues for the investment of surplus capital through imperialism. Lenin labels this period “the monopoly stage of capitalism.”

In essence, he considers this development inevitable: imperialism is inherent in the very workings of developed capitalism.

Thus, for Lenin, “capitalism became capitalist imperialism at a very high stage of its development when some of its attributes began to be transformed into their opposites, when the features of a period of transition from capitalism to a higher social and economic system began to reveal themselves all along the line.” He is referring to the contradictory process of the substitution of capitalist monopolies for capitalist free competition, the latter being the fundamental attribute of capitalism and commodity production. Our contemporary generation has experienced and continues to experience that transition, visible before us in our daily lives, as it accelerates

The monopoly, Lenin refers to, is of course the precise opposite of free competition. We have seen in the 20th and 21st centuries the creation of large-scale industry and the elimination of small-scale industry, the process leading then to still “larger-scale industry”, leading to such a concentration of production and capital that monopoly results: Lenin’s “cartels, syndicates and trusts, and merging with them the capital of a dozen or so banks.” At the same time, Lenin notes, although monopoly has emerged from free competition, monopoly does not eliminate the latter, “thereby creating a number of acute, intense antagonisms, friction and conflicts.” Thus, Lenin concludes that “monopoly is the transition from capitalism to a higher system: the monopoly stage of capitalism, or, imperialism.” And thus, from the above, his conclusion that “imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism.”

Lenin: “The division of such a world is the transition from a colonialism extended without hindrance to (“small and feeble”, he wrote elsewhere) territories unoccupied by any capitalist power to a colonialist policy of monopolistic possession of the territory of the world which has been divided up (among capitalist imperialist powers.”

However, dissatisfied with this too brief definition of imperialism, Lenin, the “bulldog” as his wife Nadezhda called him, expanded the first definition of imperialism into five essential features:

1. The concentration of production and capital developed to such a degree that it created monopolies, which play a decisive role in economic life.

2. The merging of bank capital with industrial capital and the creation—and the basis of this “finance capital”—of a financial oligarchy. (Another of Lenin’s words so fashionable today.)

3. The export of capital, which has become extremely important, as distinguished from the export of commodities.

4. The formation of international capitalist monopolies, which share the world among themselves.

5. The territorial division of the whole world among the greatest capitalist powers is completed. (Very contemporary thought, except that he did not and could not foresee the degree of ambitious greed of the USA, which would want it all for themselves.)

Therefore, “imperialism is capitalism in that stage of development in which the dominance of monopolies and finance capital have established themselves;… in which the division of the world among the international trusts has begun.”

Lenin however was not satisfied with this purely economic explanation of imperialism and intends to zero in on the relation between capitalism and the workers movement in other works. But unable to let go the economic aspects of imperialism for the moment he directs his theoretical and dialectical genius to the theories of the German Marxist, Karl Kautsky, who in 1915 attacked the fundamental aspects of Lenin’s definition of imperialism.. For example, Kautsky insisted that imperialism was not a “stage” or a “phase” of economy, but a “policy” preferred by finance capital and that imperialism cannot be identified with contemporary capitalism. Lenin instead found Kautsky’s (and that of other German Marxists in general) definition of imperialism as “worthless”: because of its insistence on the national question in that every major capitalist nation strives to simply bring under its control, or to “annex,” big agrarian regions. “Imperialism seen as annexation is very incomplete, for politically, imperialism is, in general, a striving toward violence and reaction. (Lenin, we recall, is the bulldog dialectician! For Lenin, in general, the “characteristic feature of imperialism is not industrial capital, but finance capital. The characteristic feature of imperialism is precisely that it strives to annex not only agricultural regions, but even highly industrialized regions (as in WWI, German’s desire for Belgium and France’s desire for the Lorraine.) Why? Because since capitalists have already divided up the world, they have to grab for any territory because an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry among capitalist nations for hegemony, also in order to weaken competitors. Such as today: the USA wants to bring to heel Iraq and Syria and Iran in order to weaken Russia.

Lenin quotes from Imperialism (1902) by John A. Hopson to substantiate his point:

New imperialism differs from the older, first, in substituting for the ambition of a single growing empire the theory and practice of competing empires, each motivated by similar lusts of political aggrandizement and commercial gain; secondly, in the dominance of the financial or investing over mercantile interests.

Lenin’s point is that development of such economic views leads to concentration of the world of imperialism and superimperialism, a capitalist world in a phase in which wars may cease, a phase of the joint exploitation of the world by internationally combined finance capital. For Lenin, this is a departure from Marxism. Such super-or ultraimperialism theories are reactionary in that they serve to distract attention from the depth of existing antagonisms.

After first pointing out the major areas of developed capitalism in Europe, the British Empire and the American area, Lenin indicates two areas where capitalism is not developed: Russia and Eastern Asia and other vast areas with a great diversity of economic and political conditions and an extreme disparity in the rate of development. Lenin concluded that such fables as peaceful ultraimperialism as utterly worthless, reactionary nonsense.

Thus, Lenin concludes, finance capital, as we see today in the year 2016, has increased and continues to increase the differences in the rate of development (in fact, finance capital halts development) of the various parts of the world economy. So, how else, under capitalism, Lenin asks can the solution of contradictions be found, except by resorting to violence?

PART 5 –LENIN’S MAJOR WORK: STATE AND REVOLUTION

“The state is an organ of class domination, an organ of oppression of one class by another; its aim is the creation of ‘order’, which legalizes and perpetuates this oppression by moderating the collisions between the classes…”

The Marxist Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution

State and Revolution, published in 1918, is the core of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov or Lenin’s political thought. As if dictated by Lenin’ fate, the long work was written in 1917, three months before the October Revolution, on the very eve of the revolution which he was instrumental in bringing about and was in fact interrupted by the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia. Seldom has an aphorism been timelier than Lenin’s: “It is much more pleasant and useful to go through the experience of the revolution than to write about it.” In this work of 110 pages in his collected works (73 pages in an English language Ebook format available online), Lenin develops his views on the nature of the state as an instrument of class oppression and the necessity of revolution to change things, after which he proceeds to examine the stages of the transition from capitalism to communism. In the present article about State and Revolution I have used to a great extent the same (often heavy but highly emotional and descriptive) words and expressions and stuck to Lenin’s style as much as I thought proper.

As Lenin farsightedly noted—an undermining practice continuing also today perhaps even to a greater degree than in Lenin’s time—the bourgeoisie, opportunists in the labor movements and I would add the intellectual classes, especially liberal academics, devote much time and effort to adulterating Marxism, “omitting, obliterating and distorting the revolutionary side of its teaching, its revolutionary soul. They push to the foreground and extol what is, or seems, acceptable to the bourgeoisie….” Therefore, Lenin writes that his first aim in State and Revolution is “to resuscitate the real teaching of Marx on the state.

“The state,” Lenin writes in reference to the essence of the words of Marx, “is the product and the manifestation of the irreconcilability of class antagonisms. The state arises … to the extent that those class antagonisms cannot be objectively reconciled. And, conversely, the existence of the state proves that the class antagonisms are irreconcilable.” Bourgeois ideologists, Lenin points out, accept the state’s existence where there are class antagonisms, but revise Marx in such a way as to make it appear that the state exists to reconcile classes. Thus, the bourgeois state is the good, its role being to moderate and reconcile the classes—today, for example, to reconcile the differences between the 0.00001 % and the impoverished classes in the USA for whom even food stamps are unnecessary, for whom free health care and proper education are dispensable and besides smack too much of the hated socialism.

According to Marx, Lenin writes, “the state could neither arise nor maintain itself if a reconciliation of classes were possible.” In reality, the state is an organ of class domination, an organ of oppression of one class by another; its aim is the creation of ‘order’, which legalizes and perpetuates this oppression by moderating the collisions between the classes;… to moderate collisions does not mean (claim petty-bourgeois and philistine professors and publicists) … to deprive the oppressed classes of … the means and methods of struggle for overthrowing the oppressors, but to practice reconciliation.”

In the case of the Russian Revolution of 1917, the meaning and role of the state arose and demanded action on a mass scale, But there, Lenin writes just at the time when this was happening, many left-wing Socialist revolutionaries embraced the petty-bourgeois theory of reconciliation of the classes by the state. That is all they wrote about, reconciliation, reconciliation. This petty-bourgeois class is never able to understand—precisely the same today—that the state is an organ of domination of a definite class which cannot be reconciled with its antipode (the class opposed to it).

SPECIAL BODIES OF ARMED MEN, PRISONS, ETC.

Referring often to Engels, Lenin writes that civilized society is broken up into irreconcilably antagonistic classes, which, if armed would come into armed struggle with each other. However, a state creates a special power in the form of special bodies of armed men (the army and police), and every revolution, by shattering the state apparatus, demonstrates to us how the ex-ruling class aims at the restoration of these special bodies of armed men (Lenin here is apparently speaking of counterrevolutionary action like the Whites” in the Russian civil war yet to come after the Bolshevik seizure of power. Foresight!) and how the oppressed class tries to create a new organization of this kind, capable of serving not the exploiters, but the exploited. In this case, the army of the oppressed people. The kernel of the Red Army. The army of the post-revolution against the reaction sure to come.

THE STATE AS AN INSTRUMENT FOR THE EXPLOITATION OF THE OPPRESSED CLASS

At this point, Lenin concentrates on the power wielded by the state’s officials, from the “shabbiest police servant” to the head of the military arm, as explained by Engels who places state officials as “organs above society”, which permit the dominant class to hold down and exploit at will the oppressed class just as ancient and feudal states were organs of exploitation of the slaves and serfs. However, not only ancient states, but also the Bonapartism of the First and Second Empires in France, the Bismarck regime in Germany, the Kerensky government in the Russia Lenin that was about to overthrow, and how much more so in the unrestrained power of those “above society” (unchecked militarized police and top secret agencies) in the USA today.

Bourgeois ideologists, Lenin points out, accept the state’s existence where there are class antagonisms, but revise Marx in such a way as to make it appear that the state exists to reconcile classes. Thus, the bourgeois state is the good, its role being to moderate and reconcile the classes—today, for example, to reconcile the differences between the 0.01 % and the impoverished classes in the USA for whom even food stamps are unnecessary, for whom free health care and proper education are dispensable and besides smack too much of the hated socialism.

Engels had written that in the first place, on the assumption of state power, the proletariat “puts an end to the state as the state.” Engels means the destruction of the bourgeois state by the proletarian revolution. Engels added that the state itself is a “special repressive force.” Therefore, the special repressive force maintained by a handful of the bourgeoisie for the suppression of the (masses of) proletariat must be replaced by a “special repressive force” of the proletariat for the suppression of the bourgeoisie (and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat). The reader must not be mislead by Lenin’s extensive quotes from the work of the great revolutionary Friedrich Engels; he uses them in order to express pure Leninist views.

The revolution constitutes the destruction of “the state as the state.” It is the seizure of the means of production in the name of society, The so-called “withering away of the state” refers to the period after the socialist revolution. Engels, Marx and Lenin attempt to define the form of society which will replace the crushed bourgeois state as well as the form of proletarian statehood or the democracy that remains after the revolution. But since democracy is also a state it too must eventually go. The bourgeois state is first crushed and done away with, then, what “withers away” after the revolution is the proletarian semistate. It is the state in general, the idea of the state (as a repressive force, remember, that is to wither away. The whole point of Marx. Engels and Lenin, is the justification, no, the necessity of revolution to change things, since the bourgeois will never, never “wither away” on its own. It must be crushed and eliminated by a violent revolution.. The idea of the absolute necessity of violent revolution to eliminate the bourgeois state is the heart, the core, of the thinking of Marx, Engels and finally Lenin.

TRANSITION FROM CAPITALISM TO COMMUNISM

Lenin quotes Marx: “Between capitalist and communist society lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the former into the latter. To this also corresponds a political transition period, in which the state can be no other than the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.”

This conclusion is based chiefly on the irreconcilability of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Now the question arises as to how the transition from the old to the new society can proceed. Lenin too writes that the transition from a capitalist to a communist society requires a “political transition period”, and the state in this period can only be the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.

Lenin notes in this text that “it is said that the class struggle is the main point of Marxism. That is wrong. The theory of the class struggle was created by the bourgeoisie before Marx. The true Marxist extends the class struggle to the dictatorship of the proletariat. That is the most perfect distinction between a Marxist and the ordinary petty (and the big) bourgeois.”

Lenin then asks what the relation is between this dictatorship to democracy. The answer lies in the changes democracy has undergone during the transition to communism. Although we have almost complete democracy in the democratic republic, he says, this democracy is bound by the narrow framework of capitalist exploitation. Therefore it remains a democracy for the minority (for an ever more restricted minority in capitalist states today (if what remains for them can be legitimately called democracy), only for the rich, only for the possessing classes, which Lenin compares to the democracy of ancient Greeks limited to slave owners, while in modern times the democracy, in which wage slaves hardly participate, has no meaning. It means nothing to them. Thus, Lenin concludes: “democracy for an insignificant minority, democracy for the rich—that is the democracy of capitalist society.” Especially the American reader might ponder Lenin’s conclusion of one hundred years ago. He notes that if one looks at some of the details of the suffrage (residential and registration requirements), the working of the representative institutions, press freedom, etc., we see on all side restrictions after restrictions of democracy, which effectively eliminate the masses from politics and a share in democracy. Marx too, over one hundred years ago, noted the sham and the irony of every few years allowing the oppressed to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class should be in parliament to represent and oppress them.

So the progress of capitalist democracy does not march smoothly onward to greater and greater democracy. No! Lenin pronounces, “Progress marches onward toward communism, through the dictatorship of the proletariat (achieved by violent revolution); it cannot do otherwise, for there is no one else and no other way to break the resistance of the capitalist exploiters. To provide genuine democracy to the poor, for the people, and not for the rich, the dictatorship of the proletariat applies a series of restrictions on the oppressors, on the exploiters. We must crush them in order to free humanity from wage slavery. There is no other way.”

So the modification of democracy during the transition from capitalism to communism is that it is a democracy used to crush the capitalist antagonists. Democracy for the great majority of people and suppression of the exploiters and oppressors, such are the task of the revolution and the new society.

The splendid future society, the Utopian ideal, the worker with head high and shining eyes looking forward to the splendid future depicted on crude early Soviet posters of the time when men and women now freed from the horrors of capitalist oppression and exploitation and indignation have become accustomed to the elementary rules of social life, the time when the state as such can begin to “wither away”, to modern readers smacks of hyperbolic, old-fashioned propaganda, today, in the time of subtle, cradle-to-the-grave brainwash. And Lenin’s last words in State and Revolution, written a century ago will sound like a fairy tale to people busy making money, to the elite of capitalist society. It would be preferable if the images created by Marx and Engels and Lenin appeared at least chimerical. It might surprise readers to learn that a recent survey in Russia shows that over fifty per cent of Russians would like a return to the Soviet Union. Most certainly not the elite, but the poor and the exploited and oppressed today in much of the world and I believe also in the USA would perceive hope in such words and images in Lenin’s State and Revolution. Yes, I believe so.

Gaither Stewart, based in Rome is a veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

This five part series first appeared in Greanvillepost.com