Redeeming Menstruation From Mythologies And Market

By Kandathil Sebastian

13 November, 2014

Countercurrents.org

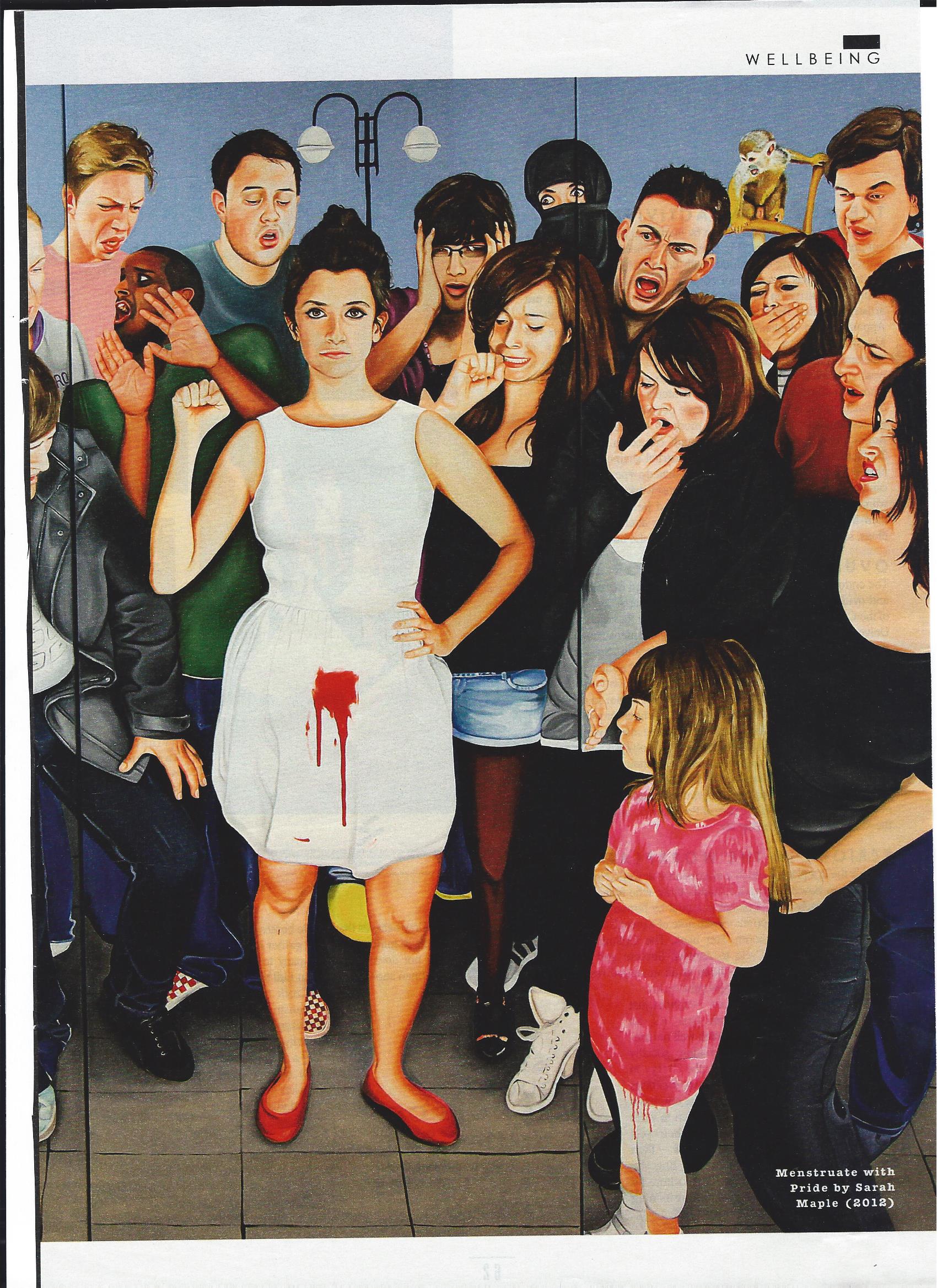

Image Courtesy: Sarah Maple/www.sarahmaple.com

Judy Grahn in her seminal work ‘Blood, Bread and Roses’ writes: “menstrual blood is the most hidden blood, the one so rarely spoken of and almost never seen, except privately by women, who shut themselves in a little room to quickly and in many cases disgustedly change their pads and tampons, wrapping the bloodied cotton so it won't be seen by others, wrinkling their faces at the odor, flushing or hiding the evidence away…”

In most part of history, society kept knowledge about menstruation in the domain of mythologies and mysteries. The deep-rooted taboos about menstruation and the long standing silence around it made menstruation as a ‘wrong’ and ‘shameful’ bodily experience and kept women away from many important social spaces and events.

But menstruation is one of the fundamental and obvious aspects of a woman’s gendered identity. Menarche proclaims the onset of maturity in girls and menstruation becomes a part and parcel of women’s lives until menopause, by indicating health and fertility of ‘normal’ women.

This essay traces the past and present mythologies about menstruation to examine how those mysterious narratives have been used for defining women’s identity and controlling their mobility. We will also analyze how the market driven modern society has created new myths around menstruation mainly to profit from the menstrual hygiene management and menstruation suppression markets.

FROM ‘SACRED’ TO ‘PROFANE’ MENSTRUATIONS

Many anthropologists vividly describe the special powers, menstruating women believed to have possessed in the earlier days of human existence. Menstrual blood was considered sacred, mighty and believed to have infinite healing powers. In the hunting and gathering nomadic societies, menstruating women guided men to find directions for a better hunting.

In agrarian societies the feminine power inherent in menstrual blood scared away storms, calmed thunders and lightning and even caused ‘caterpillars, worms and beetles to fall off from the ears of corn’. It directed warring armies of men to make peace and empowered trailing men to win battles. It was used by shamans and oracles to make very powerful magic charms and potions to purify, to destroy, to heal and to let people prosper in life.

The Mayan Moon goddess is believed to have reborn from the menstrual blood. Some anthropologists say that most women of ancient days menstruated simultaneously around the ‘new moon day’ and were let to stay secluded in ‘moon huts’ where these women performed sacred rituals for the good of the community. Women who came out of these seclusion huts were looked up and honored for their superior ‘vision’ and wisdom.

All Indian Hindus used to look up menstruating women in the ancient times. The Dravidian Hindus even today celebrate the menarche of their girl children as a festive occasion and invite their family friends to enjoy special food and music. In the Kamakhya Temple of Assam (India), the menstruation course of the goddess Kamakhya is worshipped and the menstrual blood of the deity is given to devotees as a holy offering.

Later, these ‘sacred’ myths around menstruation got transformed to ‘profane’ along with the growth of feudal societies in which patriarchal men became powerful. Most societies started mentioning menstruation as evil, polluting, painful and dirty. The religions which came up subsequently re-emphasized patriarchal notions on menstruation. In Judaism and Christianity menstruation precedes pregnancy and child birth which are punishment given to woman for tempting ‘man’ to eat the forbidden fruit. Through this suffering and pain, she was expected to know ‘the difference between good and evil.

Hinduism (with some minor exceptions) in most part of its existence, applied principles of Varnshrama Dhrama, rooted in the dichotomy of ‘purity’ and ‘pollution’ in every sphere of social life. Thus in Brahmin Hindu families, menstruating women are asked to stay away in a separate room without participating in any form of domestic chores for a period of four days. They are not allowed to enter in the kitchen or in any sacred section of the house. Those who are performers of art and dance are expected to stay away from these; those who engage in works like tailoring are not supposed to touch their tools. Everyone has to go through a ‘purification bath’ after the menstruation to get them cleansed. Interestingly in the Shabarimala temple of Kerala in India, entry of all women in their menstruating age is still prohibited.

Till recently, Brahmin Hindus in Nepal kept their menstruating women in separate huts, often in a cowshed outside their residence, during menstruation. Nepal’s ancient practice of revering little girls as Kumari goddesses till their menstruation is the theme of many celebrated books and movies. Kumaris are believed to be the incarnations of their goddess Taleju, who will desert Kumari’s body with menarche.

Islam and most sects of Buddhism consider menstruation as polluting and they will not let their women do important prayers and rituals during menstruation. Orthodox churches of Christianity prohibit women from receiving the Holy Communion during menstruation, though there is no official teaching in Christianity saying that menstruation makes women unclean in any major Christian denominations.

From the above discussion, it is clear that menstruating women enjoyed a superior position in the early days of human existence and this situation has changed later with the arrival of patriarchy. According to Charlene Spretnak “Patriarchal culture demeaned and denied the elemental power of the female body”. Considering the superior status enjoyed by women in the ancient world, this re-articulation of narratives around menstruation by manipulating the sacred images of menstruation as ‘shameful’ and ‘wrong’ appears like a deliberate attempt to subjugate women and to control their mobility in the public domain.

Menstruation mythologies and realities in the age of Menstrual Market

Menstruation taboos existed and continue to exist in almost all societies, with no visible reduction in the ‘embarrassment’ and ‘shame’ associated with it. There are many recent studies which showed that most girls, even in developed countries do not feel comfortable to talk to boys or even with their fathers about menstruation and they feel it is something which needs to be hidden. Around 60% of the women surveyed in one study are not interested in menstruating every month, out of which one third of women were interested in not menstruating at all in future.

In the modern world, knowingly or unknowingly, a new image of menstruation got deep-rooted in society – menstruation is a ‘problem’ and it is even a ‘disease’. This is the product of the newly emerged ‘menstruation market’ which conducted several commercial advertisement campaigns with such inherent images in them.

The menstruation market today is dominated by products of menstrual sanitation and menstrual suppression (which reduce or eliminate the menstrual bleeding). Menstrual sanitation products help women to hide physical symptoms of menstruation and these include napkins, tampons, cups etc. Today the market of menstrual sanitation in the world including in India is dominated by multinational companies such as Johnson & Johnson, Proctor & Gamble, Hindustan Unilever and Kimberly Clarke Lever. Products of menstrual suppression are ‘extended cycle combined oral contraceptive pills (COCP)’ and other combined hormonal contraceptives which are marketed by the big pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer. COCPs work in women’s body through effective suppression of the pituitary gland leading to the halt of development and release of the ova or egg during the ovulation period of the woman.

Emergence of menstruation market might have started with the advent Kotex sanitation products after the First World War. Sharra L. Vostral in her book ‘Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology’ brilliantly discusses how disposable and highly absorbent devices were produced as a direct result of the War, thanks to the highly efficient wound dressings developed from cellulose wood pulp, by the Kimberly-Clark Corporation in the United States. She further adds that “as technological users, women developed great savvy in manipulating belts, pins, and pads, and using tampons to effectively mask their entire menstrual period. This masking is a form of passing, though it is not often thought of in that way. By using a technology of passing, a woman might pass temporarily as a non-bleeder, which could help her perform her work duties and not get fired or maintain social engagements and not be marked as having her period”. Another writer Lara Freidenfelds in her book ‘The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America’ notes that “new expectations at school, at play, and in the workplace, made these menstrual traditions problematic, and middle-class women quickly sought new information and products that would make their monthly periods less disruptive to everyday life”.

The search for new products was also aided by the growth of modern medicine based on the germ theory which promoted an impression that for every health problem there is a clinical product to be consumed – a notion which was later effectively capitalized by the pharmaceutical industry. Earlier, most of the women in the villages used rags and old clothes during menstruation. Armed by the germ theory of diseases, modern medical science questioned safety of these age old practices of women during menstruation and propagated that such unhygienic practices would make women vulnerable to Reproductive Tract Infections (RTI’s). The Hygiene industry called for better menstrual hygiene practices which was in effect equivalent to using their sophisticated menstrual hygiene products.

The practical applications of the germ theory and the FDA approval of menstrual suppression medications opened exciting opportunities for the menstruation management industry. The preference of modern woman to avoid menstruation has offered a ready market for their products. There are reports that many adolescents are continuously using such COCPs under no expert supervision. The Society for Menstrual Cycle Research however has cautioned that safety of such use is not supported by sufficient studies. Nobody could agree with the promotion of these products as a lifestyle choice (as opposed to medical indications). Unfortunately most of the promotional literatures of COCPs remain quiet about the common side effects of irregular vaginal bleeding, spotting etc. The negative portrayal of normal menstrual cycles in the promotional literature of COCP is even more alarming.

Not only the big pharma companies but several NGOs in India also (as part of their Water, Sanitation and Hygiene projects) got pulled into the bandwagon of the menstruation mythologies of the modern age. Government of India substantially reduced the tax component of the sanitation napkins and supported its subsidized provision to adolescent girls in the country. The aggressive commercial advertisements of sanitary napkins not only promoted the sale of napkins but also re-emphasized the image of menstruation as a problem and shame (e.g. see the blue liquid used instead of real blood in the napkin advertisements to demonstrate the absorbing potential of the sanitary napkins).

While the contribution of such aggressive promotion of sanitary napkins towards reduction in the incidence of RTIs is yet to be established, it caused a huge ecological problem in many Indian cities. A recent incident in Pune city in India as reported by SWACH, an NGO is the tip of the iceberg of such an emerging problem. The city generates an estimated 10 million used sanitary pads weighing around 140 tons, per month. The sanitation workers of the corporation refused to clear sanitary napkins accumulated in the city trash bins, saying they considered handling such dirty waste ‘insulting’ to them. It is also a major health hazard as a sanitary napkin comprises over 90 percent crude oil and plastic besides chlorine-bleached wood or cotton pulp. SWACH is currently involved in helping the Pune Municipal Corporation in clearing this mess, even though the Extended Producers Responsibility clause under the Plastics Management and Handling Rules, 2011, clearly states that it is the manufacturers’ responsibility to ensure that they are responsible for their products till the very end after they are used.

THE FUTURE OF MENSTRUATION

The emerging menstruation market in India is huge. In 2010, a leading manufacturer of sanitary napkins conducted a nationwide survey with the help of AC Nielsen, a research agency through a reputed NGO and the findings are mind blowing. Only 12 percent of the 355 million menstruating women in the country use sanitary napkins. Interestingly, only 2 percent of women in rural India use sanitary napkins, even though three-quarters of the Indian population lives in rural areas. The present consumption of napkins in India is estimated to be only 2,659 million pieces per year. This implies that to those who are looking for a huge menstruation market, India is their future! Creating wide sanitation awareness through substantial advertising will generate huge demand for most of the products available in the menstruation market.

In Europe and in the United States, use of sanitary napkins has already reached more than 90% and its market has already got saturated. There are about 300million women in India, aged 15–54 years. A woman will use an average of 10,000 pieces of sanitary napkins within 30–40 years in her entire lifetime, which is 58,500 million pieces per year for the entire India. A pack of eight sanitary napkins of Procter & Gamble or Johnson & Johnson would cost between INR 30-80. Thus the market of sanitary napkins in India worth more than INR 46,80,000 million per year. Similar estimates can be made for other products of the sanitation market too.

While India moving ahead with its Clean India campaign, there is renewed scope for several cleanliness products in the emerging hygiene market. If we want to ensure that women’s health is not a casualty amidst these hygiene campaigns and products, we need to begin our work by promoting two key ideas:

1. Menstruation is a normal and fundamental aspect of a woman’s gendered identity - it is not a myth, a mystery or a problem to be solved.

2. Women’s health as well as overall health of each and every individual in the society is not dependent on consuming new products that are cleverly marketed as antidotes to our illnesses.

We must also remember that women and girls have been coping with menstruation for a long time without the aid of the new fantastic plastic convenience. Whatever traditional methods they have been using including old reusable clothes may have inherent wisdom which could be re-discovered and further refined through indigenous research to offer them as hygienic options. Freeing our minds from the myths of ancient days as well as from the myths of the modern market is the way ahead for our sustainable future.

Kandathil Sebastian is a Public Health Researcher and an International Development Consultant. He is also the author of two fiction novels – ‘Dolmens in the Blue Mountain’ and ‘Wisdom of the White Mountain (forthcoming)’

Comments are moderated