Nine Low-Tech Steps For Community Resilience In A Warming Climate

By Kaid Benfield

03 April, 2012

NRDC’s Switchboard

Over the past 50 years, our average global temperature has increased at the fastest rate in recorded history. That is fact, not opinion. Scientists say that under current trends, average US temperatures could be 3 to 9 degrees higher by the end of the century.

This is not abstract, nor are the effects limited to the developing world. These changes will have – indeed, are already having – major effects on our cities, suburbs, and towns. Chicago is becoming warmer. So is Orlando. So are Spokane and Dallas. So are smaller towns such as Louisville, Colorado and suburbs such as Gaithersburg, Maryland. Everyone has weather, and everyone’s weather is getting warmer. By fits and starts, to be sure; but, if you don’t believe it, ask a landscaper. The serious impacts beginning and yet to come are not pretty and, as my colleague Kim Knowlton has reported, even the insurance industry is noticing.

There are many things we can and must do to reduce the warming trajectory. First among these is reducing emissions of carbon dioxide, the most common and potent greenhouse gas, particularly by transitioning to a clean energy economy. But turning this ship around is going to take time, even under the best scenarios.

Meanwhile, there are also measures we need to take right now inside our communities so that we are as prepared as possible for the warmer climate ahead. Some of them are related to technology, of course, perhaps including personal technology. But that isn’t my personal strength as an environmental observer. This article focuses on a few things that we can and should do for our cities, suburbs and towns that are low-tech. What’s below is by no means a definitive or complete list, but it’s a start:

1. Bring more vegetation into neighborhoods. I’ve written often about the benefits of green infrastructure – green roofs, roadside plantings, rain gardens, swales, and so forth – to stormwater management, and I’ve applauded the way these practices can bring bits of nature into our neighborhoods. But they also lower the temperature, compared to hard surfaces, and absorb carbon dioxide from the air. So do street trees and parks large and small.

2. Plant city-scaled community gardens. One type of vegetation that is a special case is gardening, including small urban orchards (such as the one incorporated into the plan for Via Verde in the South Bronx). These, too, can help lower temperature, and growing some of our own food right in our neighborhoods can also reduce the number of errands we need to run, while increasing health and fitness. Health and convenience are good things in a warming world. But note my caveat that they must be the right scale, to enhance and complement walkable urban densities, not displace or preclude them.

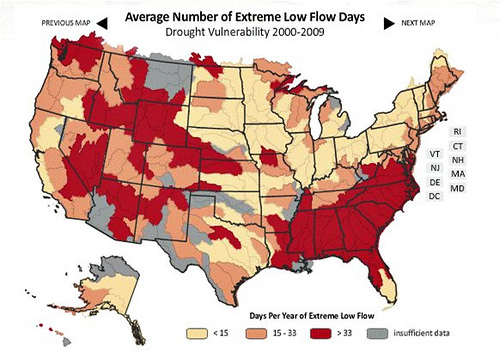

3. Use drought-resistant landscaping. It’s going to be not just warmer but also drier in many communities. We should use native species and xeriscape wherever possible, so that homes, offices and neighborhoods can enjoy the benefits of attractive landscaping without exacerbating water shortages. In fact, when practiced collectively, drought-resistant planting can help stave off the water shortages likely to come more frequently with warmer temperatures.

4. Use light-colored roofing and pavement. Dark surfaces absorb heat, while light-colored surfaces reflect it. Writing in Clean Technica, Zachary Shahan reports that, on the hottest day of the New York City summer in 2011, a white roof covering was found to be 42°F cooler than the traditional black roof it was being compared to. That is an amazing difference that not only helps reduce the on-site temperature but also lowers electricity demand for air conditioning, which in turn reduces carbon emissions from power plants. This finding was part of a study led by scientists at Columbia University and announced by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Earth Science Division. (Shahan also notes that an earlier study that claimed a net warming effect in the atmosphere globally from white roofs failed to account for the reduced energy demand.)

5. Get serious about sea level rise and storm surges. It’s making less and less sense to build in low-lying parts of coastal areas. As my colleague Dan Lashof recently wrote, what used to be a storm of the century is becoming a storm of the decade. Last week, researchers at Climate Central published studies and released an interactive map that shows increasing flooding risk for the entire US coastline. Anyone who lives near the coast can enter her zip code and see a localized map of the areas that will flood at various storm surge levels. Dan examined a map of Virginia Beach, for example, showing that a four-foot storm surge (which has about a one-in-three chance of occurring in the next twenty years as sea levels rise) could flood more than 10,000 homes and affect almost 30,000 people. We should make sure that flood plain demarcations take account of warming trends, and keep future buildings out of those zones.

6. Save older buildings. New construction generates heat and disrupts existing vegetation while frequently failing to generate carbon-reduction benefits over older buildings, even with newer and more efficient technology. Our older buildings also remind us who we are as a community, and tend to knit together existing neighborhoods.

7. When building new, follow “Original Green” practices. Especially in a warmer climate, it is important that buildings be constructed and sited to take advantage of natural processes. Bring back real front porches. Plant deciduous trees on the south side, where they provide shade in summer while allowing sun in the winter. Plant evergreens on the side that will benefit by protection from winter winds. Use close-to-the-source materials and naturally insulating design. Place new buildings in walkable settings with everyday conveniences nearby.

8. Keep the regional footprint small and well-connected. Sprawl exists, and it will take some time to repair or retrofit it into a more sustainable pattern. But, in the near term, we absolutely should not add to it. This means no more leapfrog development, period. Instead, we should accommodate growth by inclusive revitalization, grayfield and brownfield redevelopment, and the right kind of infill that enhances neighborhoods without overwhelming them. Internally to our communities, we must make public transit robust and walking and bicycling to common destinations easy.

9. Update our zoning and building codes to facilitate resilience. As I observed just last month in my article on DC’s current zoning update, in most communities it will take affirmative code amendments to make walkable, diverse neighborhoods legal again. Let’s do it.

While this article focuses on strengthening communities in the face of climate change, these steps also provide other kinds of resilience. Since fuel prices will continue to rise, for example, reducing demand for electricity and gasoline through smart building and growth management conserves financial resources. So does obviating the construction of infrastructure expansion to accommodate sprawl and employing green techniques to manage stormwater instead of building larger concrete sewer and drainage pipes.

As I wrote at the outset, this isn’t meant to be a definitive list. Nor is it intended as an antidote to global warming. Rather, it’s meant to start a conversation about the reality of a warming climate and what we can do with our built environment to respond to it in the most realistic and sustainable way. What would you add to the list?

Kaid Benfield writes (almost) daily about community, development, and the environment. For more posts, see his blog’s home page.

Due to a recent spate of abusive, racist and xenophobic comments we are forced to revise our comment policy and has put all comments on moderation que.