An Ode To Seasons For Peter Matthiessen

By Subhankar Banerjee

07 April, 2014

Climatestorytellers.org

(r to l): Peter Matthiessen, Jim Campbell and Tom Campion. Utukok River Upland, Western Arctic, Alaska.

(Subhankar Banerjee, June 2006).

Do you know about Peter Matthiessen?

Maybe you’ve read one or more of his many unforgettable books. Snow Leopard, perhaps? Or maybe, Shadow Country? Both, one non–fiction and the other an epic novel, had won the National Book Award. The list of books he wrote is rather long. You may have read more of his books than I have.

Peter Matthiessen passed away on Saturday, at his home in Sagaponack, New York. He was 86. I’m sure you will read about him in many places now.

Peter was one of the greatest human beings to have ever lived on this Earth. He loved wild places and animals. He fought for the indigenous peoples and conservation of nature…all his life.

And, he should have won a Nobel Prize for literature.

For me, and I humbly say this: Peter was my friend, my mentor; he stood by me whenever I reached out to him for help, including when I went through a difficult phase during the Bush administration, in 2003. He is one of the most compassionate people I’ve ever met in my entire life.

I had the good fortune to take him to the Arctic, three times.

I present this piece to you with teary eyes and a broken heart.

This piece is for Peter Matthiessen (not about him), and about what he loved and fought for through his writing.

I think he would have liked it, and probably would have said: “Not bad, Subhankar. Are you trying to become a writer now, or what?”

I begin with a short paragraph Peter wrote in his essay, “In the Great Country”, in my first book, Seasons of Life and Land: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Mountaineers Books, 2003):

“Tonight camp is made on soft, wet moss at the foot of the last river bluff before the plain. An hour before we came ashore, we had seen two figures waving from the high rim of the escarpment—Subhankar Banerjee and his partner, an Iñupiat named Robert Thompson. Camped a half–mile upriver, they turn up at our camp in time for supper. Subhankar tells us that this very day, he and Robert have found gyrfalcons and peregrines nesting on rock towers close together; in recent days, they have seen muskox here as well as grizzlies.”

That was in the Kongakut River valley, in 2002.

In the Karen Creek

In early April 2001, Robert Thompson and I had done a winter trip in Karen Creek, in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. I remember vividly the magnificent snow–covered Mount Chamberlin, towering above three moose and hundreds of ptarmigans, on the valley below.

Fast forward to now. Few days ago Robert wrote to me in an email: “I was in the Karen Creek area; all our animals are gone; no moose, no caribou, and no muskox; 0; not even many ptarmigans, strange.”

After writing a series of argumentative pieces recently, my hands are hurting from all the punching and my legs are in pain from all the kicking.

Spring has arrived. I shelve arguments for now, to sing an ode to seasons, and celebrate all that we still have (even as we acknowledge that seasons are changing and the animals are vanishing).

Some of us say that “spring is here” when the trees burst out with lime green leaves, after the snow melts.

But do you know who is the harbinger of spring in the Arctic? It’s a tiny songbird, the Snow Bunting. It weighs less than two ounces; some people say that even on a warm day its mostly white plumage “evokes the image of a snowstorm.” It winters in the mid–latitudes, and migrates to the high Arctic, in early April, for breeding.

Right now temperatures in the far North hover around say minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit, some days colder, some days warmer. The ground is covered in snow. The ocean is frozen. It’s white almost everywhere. One way you can tell the difference between land and the sea—is by walking. The surface of the sea is very rough, compared to the land, which is relatively smooth.

If you talk to the Iñupiat people in Kaktovik, however, they will tell you “spring is just around the corner.” But how so?

Kaktovik is a small Iñupiat community of about 300 people, on the northeast coast of Arctic Alaska. Robert and his wife Jane live there. It was mid–April, in 2001. I step out of Robert’s house onto the snow–covered ground. It’s cold, and the snow will not melt for another month or so. The Snow Buntings arrived while Robert and I were at Karen Creek. They seem cheerful as they sing their hearts out. Jane is very happy to see them, and so is the rest of the village. She tells me about all the different places the little creatures are going to be nesting. Buntings have brought a promise with them: “Winter is over, and spring is just around the corner.” This is an important promise to a town that has been blanketed in snow for months, with blizzards and darkness for much of the time.

Buntings are likely singing in the Arctic, as I write this.

Do you know that Terry Tempest Williams wrote about the Snow Bunting in her epic book, Reguge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place?

Terry and I did several events with Peter Matthiessen for our ongoing campaign to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Last evening Terry wrote to me: “Peter was our elder, our mentor, our teacher. His edge made us all sharper.”

Hunters in the Snow

Do you know who was the first artist to sing the glories and hardships of seasons in expressly ecocultural terms? It’s likely Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the famous 16th century Flemish Rennaissance painter.

In 2007 Peter Matthiessen and I participated in a UN Environment Programme panel on climate change at the Palais des Beaux–Arts in Brussels. While there, we saw several paintings by Bruegel at the nearby Musées royaux des Beaux–Arts de Belgique.

In 1565 Bruegel painted a series of landscapes that represent the seasons of the year. There remains uncertainty over how many he painted in the series, but it is widely believed today that the number was six, five of which survive. These five paintings collectively have come to be known as the “Seasons” series.

Moreover, which painting represents which two months isn’t precisely known either, but at least one scholar has suggested this association: Hunters in the Snow, also known as Return of the Hunters (December–January), Gloomy Day (February–March), [the missing work (April–May),] Haymaking (June–July), The Harvesters, also known as the Corn Harvest (August–September), and Return of the Herd (October–November).

I won’t go into a full discussion of the paintings, but only point out couple of things that may relate to what I’m about to present below.

Hunters in the Snow. Pieter Breugel the Elder, 1565. (source: Wikimedia Commons).

Breugel painted each work with a limited color palette. Take for example, the Hunters in the Snow, one of the greatest paintings in the history of painting, was done with—white (snow), greenish grey (ponds/river ice), light grey to almost black (people, birds, trees, some of the dogs, exposed rocks on the mountain peaks), and just a touch of yellow to reddish brown (foreground foliage, some of the dogs, facades of buildings and bridges).

The Hunters in the Snow is also known for its complex ecocultural narrative. Three hunters return with only one of them carrying a rabbit for all their hard work. The hunters and the dogs are trudging in the snow, with their heads down, alluding to an exhausting and unsuccessful hunt. But as our eyes move from the hunters and dogs in the foreground left, to the middleground right, we see townspeople are engaged in play—ice skating on frozen ponds; while some others go about their daily chores in various parts of the image.

It’s obvious that Hunters in the Snow draws our attention to the difficulty of harvest during the harsh winter season. It’s worth noting here that Europe was in the midst of a Little Ice Age when Breugel painted the scene. The artist, paying close attention to the environment, perhaps also inadvertently gestured towards a larger truth—that in a changing, harsh climate—harvest becomes a difficult task.

Isn’t the latest IPCC report saying something similar—that in our rapidly warming Earth now (a changing, harsh climate)—the production of and access to food will continue to become increasingly difficult?

Seasons in the Arctic

I’ll now share with you six of my own photographs from the Arctic (with small commentaries), as a celebration of life in the far North. From the beginning, I had organized my work around the seasons.

We can think of each photograph, more–or–less representing two months: Caribou Migration II (April–May), Loon on Nest (June–July), Snow Geese I (August–September), Fish and the Yukaghir (October–November), Gwich’in and the Caribou (December–January), and Bear Playing with Her Cubs (February–March).

I too work with a limited color palette.

In the photographs you see humans engaged in labor in the landscape, not unlike Breugel’s paintings; although Breugel had also included leisure as well. You will, however, see a lot more of nonhuman animals in my images, than in the paintings of the Flemish master.

When human survival is continuously being threatened by varieties of anthropogenic injuries (ecological, economic, social), our capacity to think about the nonhuman animal become very limited indeed. Nevertheless, it is our ethical obligation to also consider their survival as well.

Regarding the nonhuman, it’s worth quoting a few lines from a writer who also sang about the seasons. This is how Henry Thoreau had begun Walking:

“I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil—to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society. I wish to make an extreme statement, if so I may make an emphatic one, for there are enough champions of civilization: the minister, and the school committee, and every one of you will take care of that.”

Let us begin with spring then. For some it is the melting of snow, for others it is the arrival of a bird, and for some others it is about movement.

Caribou Migration

The pregnant female caribou of the Porcupine River herd will begin, in just a few days, their spring migration from the winter grounds in the south side of the Brooks Range Mountains in Alaska, and the Ogilvie and Richardson Mountains in Yukon Territory, Canada. It’s an arduous journey, in which the caribou will walk hundreds of miles, across frozen river valleys and through snow–covered mountain passes, to reach by end of May, their ancestral calving grounds, in the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The caribou will give birth within the first ten or so days in June.

I’m deeply grateful to biologist Fran Mauer, who studied the Porcupine River herd for years, and had encouraged me to visually portray their epic spring migration.

Here then is Caribou Migration II, with white, turquiose, brown and grey.

Caribou Migration II. Coleen River Valley and Brooks Range Mountains, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

(Subhankar Banerjee, early May 2002).

Loon on Nest

You might have heard about “cry of the loon,” or even “loon’s yodel.” Do you, however, know that this large, bulky, beautiful waterbird is one of the longest surviving species on Earth?

In July 2002, David Allen Sibley, Robert Thompson and I were cramped inside a tent that was about to collapse, during a summer storm that likely was blowing at 80 mph. We had camped along the shore of the Beaufort Lagoon, in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Besides the storm, the around–the–clock calls of the loons and the cranes, and the midnight sun, kept us awake at all hours.

David’s wildly popular book, The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior, says this about loon’s antiquity:

“Loons constitute one of the more ancient bird lineages; fossil evidence of loon–like birds dates back well over 70 million years to the late Cretaceous period, and birds resembling modern loons are known to have occurred some 20 million years ago during the Miocene epoch. This means that loons survived the great upheavals in Earth’s atmosphere that took place between the late Cretaceous and the Tertiary periods.”

Do you know about Jeff Fair? It’d be fair to say that Jeff Fair, the humble biologist–writer is our loon poet. On 5 March 2013, he wrote to me in an email in response to an earlier conversation we had:

“The extreme antiquity of loons on earth was apparently exaggerated based on some early assumptions. The most recent information that I’ve (just now) come across in writing a preface for a recent symposium on loons, is that the fossil record for loons reaches back only 40 million years (Eocene) and not to the Cretaceous (70+ million years).”

“Only” 40 million years, Jeff? It’ disappointing to know that loons are not that ancient after all.

I’m, however, curious to know now—How does a fairly large size species like loon survive both in an icehouse Earth (in which we have been living continuously for about 34 millions years), and in a hothouse (or greenhouse) Earth (in which humans have never lived)?

Here then is Loon on Nest, with black, white, grey, and just a touch of green in the grass and red in the eyes; with a few words from an essay I wrote last year in the Third Text journal:

In these bird portraits we do not get much information about their natural history but instead a psychological state of being–in–the–land. The loon sleeps briefly, then wakes up, and rotates its head to look around. I had known that when resting outside its breathing hole on the ice a seal would use a sleeping–waking–looking method to protect itself from polar bears, its predator. I surmise that the loon (besides being curious) was keeping an eye out for predators, like the Arctic fox, that would try to get the eggs—at times the fox wins. Whether it was a clear day with the temperature at about forty degrees Fahrenheit, or a day when snow fell incessantly with temperatures around twenty degrees, the loon sat on the nest and rotated its head. There were breaks too—an exchange, as both male and female bird share nesting duties, giving each other breaks to go and feed. Did my presence have impact on the loons’ behavior? Quite possibly, but they did sleep in my presence too.

The Loon on Nest accompanies a revised version of Peter Matthisssen’s “In the Great Country,” which was published in the anthology, Arctic Voices: Resistance at the Tipping Point that I edited (Seven Stories Press, 2013). Peter loved birds as much as anything else. He was a birder extraordinary. In autumn 2002, Peter and I had done an event for the Manoment Center for Conservation sciences in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Earlier in the day, our good friends there took us out birding on Plymouth Beach. That day we saw American Golden–Plover, Ruddy Turnstone, Dunlin, Semipalmated Sandpiper, and Semipalmated Plover, species that Peter and I had seen only a couple of months before in the Arctic Refuge.

Loon on Nest. Kongakut River Delta, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Subhankar Banerjee, late June 2002).

Snow Geese Aggregation

Nearly 300,000 snow geese arrive from their nesting grounds in the Nunavut Territory, in the Canadian high Arctic, to the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, in early autumn, which lasts from mid August through early September. The geese feed sixteen hours a day on a type of cotton grass to build fat, before they start their long migration south to places like New Mexico, California, Texas, and Mexico.

The aggregation of geese in autumn (late August – early September) and the post–calving aggregation of caribou, often with more than 100,000 animals, in summer (late June – early July), almost overlap in space, in the Arctic Refuge coastal plain. Even though the caribou and geese eat two different types of cotton grasses, apparently the caribou droppings fertilize the tundra for the cotton grass that the geese eat.

Fran Mauer told me about this unusual caribou–geese ecological connection, and had encouraged me to take a picture of the geese aggregation as well.

Here then is Snow Geese I, with white, brown and blue.

Snow Geese I. Jago River Valley, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Subhankar Banerjee, September 2002).

Fish and the Yukaghir

In November 2007, on an assignment from Vanity Fair, I went to Siberia with Robert Thompson. We spent three weeks there, first in an Eveny reindeer camp in the Verkhoyansk Range, the coldest inhabited place on Earth, where temperatures drop to minus 98 degrees Fahrenheit (without windchill) in January, and then in the Yukaghir community in Nelemnoye.

Yukaghir ecocultural conservationist and researcher Vyacheslav Shadrin had graciously taken us to Nelemnoye. There, we stayed with an elderly couple, Nikolai Shalugin and Evdokya Shalugina. I remember having at least seven meals a day, all of them included fish that Evdokya prepared in many different ways, one of which tasted just like the doi maach that my mom makes back in Bengal.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the Yukaghir people occupied the vast and the entire territory of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), which is the largest subnational entity in the world, and is roughly the size of Western Europe. Due to many reasons of Tsarist expansion, Sovietization, disease and expansion of other indigenous tribes, the Yukaghir population declined massively; today they inhabit only two communities along the Kolyma River: one in the Verkne Kolymsk region (upper Kolyma) and the other in the Nizhne Kolymsk (lower Kolyma).

The Yukaghir people of Nelemnoye primarily depend on subsistence hunting and fishing. Since there aren’t enough elk (in Alaska the same animal is called moose) to provide adequate meat for everyone in the community, the primary subsistence food in Nelemnoye is fish. The village is along the Yasachnaya River, which provides plenty of fish for the community.

The fish that Nikolai Shalugin caught during our visit were primarily broad whitefish, with some grayling and two lingcod.

Here then is Fish and the Yukaghir, with white, light and dark grey, and a touch of reddish brown.

Fish and the Yukaghir. Nikolai Shalugin and Vyacheslav Shadrin, Yasachnaya River. (Subhankar Banerjee, November 2007).

Gwich’in and the Caribou

Peter Mathiessen and I are what you might call kindred spirits, as he once wrote: “Subhankar Banerjee and I have a strong bond rooted in the fact that much of our recent work is inspired by Alaska’s threatened hunting peoples and the wildlife they depend on, whether on land or sea or on the disappearing ice.”

Peter cared deeply about the Gwich’in people. He was a friend of Gwich’in elder and cultural activist Sarah James. If you’re curious about the collaboration among the three of us, you might like to hear the audio of a Lannan Foundation event we did together in Santa Fe, in 2004.

The Gwich’in people of Alaska, and the northern Yukon and Northwest Territories in Canada, live on or near the migratory route of the Porcupine River caribou herd (the same caribou you saw in the migration photo above), and have relied upon the caribou for many millennia for subsistence as well as their cultural and spiritual needs. The Gwich’in are “caribou people.” They call the calving ground of the caribou: Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit (The Sacred Place Where Life Begins). To open up the caribou calving ground to oil and gas drilling is a human rights issue for the Gwich’in Nation.

Sarah James always says: “We are the caribou people. Caribou are not just what we eat; they are who we are. They are in our stories and songs and the whole way we see the world. Caribou are our life. Without caribou we wouldn’t exist.”

Here then is Gwich’in and the Caribou, with white, red, and grey to black.

Gwich’in and the Caribou. Danny Gimmel, near Arctic Village. (Subhankar Banerjee, January 2007).

Bear Playing with Her Cubs

While Breugel showed us a Gloomy Day in (February or) March, I’m instead showing you a playful day in March.

Polar bears den both on land, and on the sea ice. I’m writing about only the terrestrial dens, because that’s what I saw. The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain is the only land conservation area in the United States for denning polar bears. A pregnant female would go inside a temporary den (which she makes inside a simple snowbank) in October–November; give birth during December–January; and nurse her cubs inside the den until March (or early April), at which point she would emerge from the den with usually one or two cubs. Each day she would play with the cubs outside the den for about twenty or so minutes, to exercise. After a week or two, the family will head out for the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. At that time, the mother bear has not eaten for five to six months; she will need good spring sea ice for seal hunting to feed herself and to nurse her cubs.

As I write this, a few of the bears and cubs are likely still engaged in exercise and play in the Arctic Refuge coastal plain, and getting ready to leave for the sea ice.

Here then is Bear Playing with Her Cubs, with white, yellow–white, bluish–white, and grey.

Bear Playing with Her Cubs. Canning River delta, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Subhankar Banerjee, late March 2002).

An Unexpected Discovery

Each time we have a need to sing an ode to seasons, we summon up—the poet, the artist, the writer, the musician, the theatre director… But what about the scientist?

This might come as a surprise to you that one of the most poetic portrayals of seasons as it relates to the living Earth, was made visible, (it seems to me) not by an artist or a poet, but instead by the work of a climate scientist.

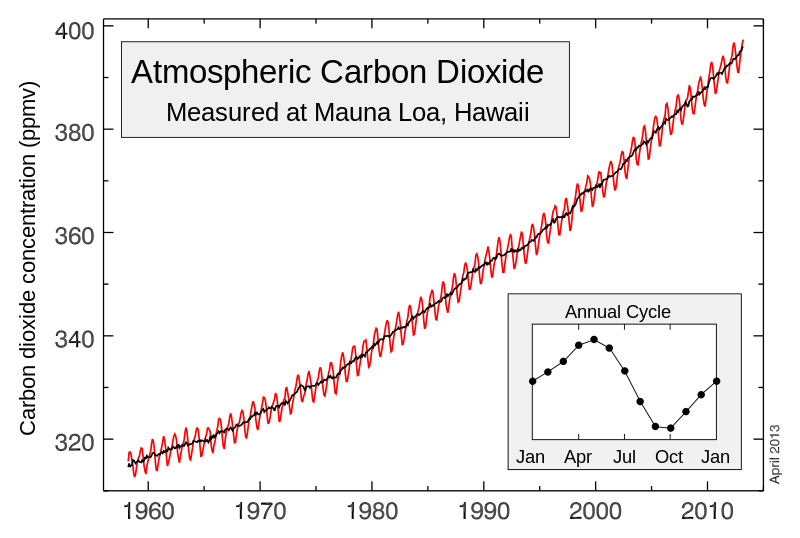

Charles David Keeling began measuring atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration at the summit of Mauna Loa, in Hawaii, in 1958. You may remember that the carbon dioxide concentration at Mauna Loa had reached 400 ppm, on 9 May 2013. Within a year or two the global average will also reach 400 ppm. The last time atmospheric carbon dioxide level is thought to have reached 400 ppm was in the Pliocene, more than 2.5 million years ago.

Keeling’s seemingly simple experiment is considered today a momentous achievement in science. The Keeling record has informed three major discoveries: that the carbon dioxide concentration is going up (consistent with the anthropogenic burning of fossil fuels, changing land use and deforestation); the uptake of carbon dioxide by the Earth System (atmosphere, oceans, biosphere); and the potential for carbon–climate feedbacks.

The Keeling record also revealed something quite unexpected.

The Keeling Curve: 1958–April 2013. (source: Wikimedia Commons).

David Schimel wrote a lovely passage about the unexpected discovery from the Keeling record, in his book, Climate and Ecosystems (Princeton Primers in Climate) (Princeton University Press, 2013):

“One of the notable features of the [Keeling Curve] is the strong seasonality it shows, as an oscillation around the [almost linear] upward trend. This oscillation, called the breathing of the Earth results from Northern Hemisphere summer…photosynthesis, or the winter decomposition of dead plant material. This was one of the least anticipated discoveries, because when Keeling began his work, climate science was dominated by geophysics, and no one suspected that life could so visibly and systematically alter the atmosphere. The seasonal cycle provides global quantification of the effect of seasonal climate on ecosystems.”

As you can see, the Earth is not an inanimate blob of geology, but rather a living, breathing entity replete with seasons.

A Short Report from Home

While the animate Earth isn’t losing touch with the cycles of seasons, we modern humans, however, are rapidly losing touch with it—by being inside (home, car, office) … most of the time (with comfortable temperatures made possible by heaters or air conditioners) … mostly sitting (on chair, couch, car seat).

“But what will I see, if I go outside?” you might ask.

Maybe life. Maybe resistance. Maybe destruction. Maybe restoration. I don’t know.

But now that spring has arrived, here are a few things I’ve been seeing lately, along the beach, not far from where I live: about a dozen sandpipers pacing the beach making prints on the wet sand only to be washed away by waves; a pair of Harlequin ducks, you know the really colorful one…preening atop a small rock, partially submerged in water; a pair of oystercatchers, you know the one with deep–red, long beak…finding food in the shallow water of the low–tide; and that bald eagle, the one that almost always sits atop a tall Douglas fir on the bank, high above the water, suddenly flew out and landed on another partially submerged rock, not far from where I was heading. I stopped; who needs a binocular when the big bird is so near? By the time I got to the bend from where you can see the little island, I was tired. I sat down on a log…quite a ways out in the water, porpoises were playing or feeding, I couldn’t figure out. The crows and the gulls were not only causing ruckus, but some were trying to drop poop on my head; fortunately the wind was on my side that day.

Peter Matthiessen in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

I learned how to pay close attention to the nonhuman world, in part by being with Peter Matthiessen in the Arctic.

Here is one of my most favorite passages from his Arctic Refuge essay, “In the Great Country”:

“Out of the wind, leaned back against soft lichens on the rocks, we breathe in a vast, beautiful, and stirring prospect. High snow–streaked peaks rise to the south and west, and to the north, the gray torrent, curving west under its cliffs, escapes the portals of the foothills and winds across the plain toward the hard white bar on the horizon—the dense wall of fog that hides the Beaufort Sea. This wild, free valley and the barren ground beyond is but a fragment of one of the last pristine regions left on earth, entirely unscarred by roads or signs, indifferent to mankind, utterly silent.”

His outrage was equally sharp: “I am outraged that the last pristine places on our looted earth are being sullied without mercy, vision, or good sense by greedy people who are robbing their fellow citizens of the last natural bounty and profusion that Americans once took for granted.”

Peter Matthiessen wrote passionately against oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and advocated for its permanent protection. The Refuge continues to remain free of industrial development.

He also wrote passionately against oil drilling in the Arctic Ocean. In 2007 we did a trip together to the Iñupiat communities Point Hope and Point Lay. His essay, “Alaska: Big Oil and the Iñupiat–Americans” was published later that year in The New York Review of Books. In the essay, regarding the dangers of oil drilling in the Arctic Ocean, he wrote:

“A black effluvia of crude petroleum and drilling mud and chemical pollutants would spread inshore, suffocating plankton and invertebrates and bottom–dwelling fish and poisoning great stretches of Arctic coast with a viscous excrescence. The same toxic mixture will blacken the drifting ice, fouling the pristine habitat of Arctic birds, the Pacific walrus, four species of seals, and the beleaguered polar bear, while contaminating the migratory corridors of the white beluga and endangered bowhead whales—all this defilement made much worse by the grim fact that no technology has ever been developed for cleaning up spilled oil in icy waters.”

Peter Matthiessen drew our attention to the inter–generational ecocultural injustice by ending the Arctic Refuge essay with these words: “If we fail to save the land, God may forgive us,” as a Togiak elder has said, “but our children won’t.”

Peter, rest in peace. I love you. I miss you. I’m crying.

This article and all the accompanying images may be reproduced free of charge by any person or publication, without permission from ClimateStoryTellers or the author.

Subhankar Banerjee is a photographer, writer, and activist. His most recent book is Arctic Voices: Resistance at the Tipping Point (Seven Stories Press). He was recently Director’s Visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, Distinguished Visiting Professor at Fordham University in New York, received Distinguished Alumnus Award from the New Mexico State University, and Cultural Freedom Award from Lannan Foundation. For more information visit his website www.subhankarbanerjee.org

Copyright 2014 Subhankar Banerjee

Comments are moderated