Babloo Loitongbam: Three Decades Of Building Human Rights Solidarity

An Interview With Babloo Loitongbam By Abhay Kumar

22 March, 2015

Countercurrents.org

Almost three decades back, Babloo Loitongbam left his hometown Imphal for Delhi, with an aim to prepare for civil service exams. But he could not have ever thought that he would encounter racial discrimination and prejudice in the national capital. As a result, he grew conscious of his identity and was brought closer to North-East associations of Delhi. This was perhaps the beginning of politicisation of Babloo. As the early period during 1990s saw intensified military repression in North-East regions, coupled with Hindutva assault over the Babri Masjid-Ram Temple controversy, he gravitated towards radical Left organisations, protesting more in the street rather than taking notes in class. With the passing of time, he increasingly got associated with the campaign against human rights violations in North-Eastern states. Recently, he has been on the news when the Manipur Legislative Assembly served him a breach of privilege notice, for allegedly making “derogatory” remarks against legislators. Amid the looming threat of a possible arrest, Babloo managed to rush to Delhi to participate in a meeting of human rights activists held in the last week of February. In a conversation with Abhay Kumar, on February 28, over a lunch in School of International Studies’ canteen of Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, noted human rights activist and executive director of Human Rights Alert, Babloo Loitongbam spoke about a large number of issues, including AFSPA (Armed Forces Special Powers Act), his association with Irom Sharmila and increasing processes of militarisation in India over the decades. The excerpts of the interview are as follows:

When did your activism in the field of human rights begin?

In 1988, I came to Delhi from my home town Imphal and got enrolled in Hansraj College of Delhi University as an undergraduate student. My parents wanted me to prepare for UPSC [Union Public Service Commission] exam. But in the national capital including the University of Delhi, I experienced racial discrimination and prejudice and was derogatorily called chinki. Moreover, I found that the people from North-East regions were stereotyped as violent and irrational. In the wake of this, I got associated with Manipur Student Association, which was formed in the early 1970s and North-East Student Federation. A year later in 1989, I became the General Secretary of Manipur Student Association. As the early 1990s saw a spurt in the Indian Army’s atrocities in Manipur as Operation Sunny Vale and others were launched, I started participating in protests and thus, I gravitated more and more towards Left and other progressive organisations, and human rights organizations like PUDR [The Peoples Union for Democratic Rights].

How was the transition from a civil service aspirant to a radical political and human rights activist? Was not easy for you?

Having passed B.Sc (Anthropology), I enrolled myself in Law as I thought it may be a more appropriate subject for changing the system. But in the second year, people’s movements for secularism emerged and we had conflicts with ABVP [Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, BJP’s student-wing]. Since I was too active in politics, I did not pass the exam and I was thrown out of the hostel. My image as a rebel also contributed to the expulsion. Having rendered roofless, I had to stay with a Dalit and I paid him 400 rupees a month. This enabled me to experience the caste system. As I had failed in the exam, I felt ashamed to ask money from my father and thus I joined South Asia Human Right Documentation Centre as a volunteer. For this work, I got some money that sustained me.

Having passed B.Sc (Anthropology), I enrolled myself in Law as I thought it may be a more appropriate subject for changing the system. But in the second year, people’s movements for secularism emerged and we had conflicts with ABVP [Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, BJP’s student-wing]. Since I was too active in politics, I did not pass the exam and I was thrown out of the hostel. My image as a rebel also contributed to the expulsion. Having rendered roofless, I had to stay with a Dalit and I paid him 400 rupees a month. This enabled me to experience the caste system. As I had failed in the exam, I felt ashamed to ask money from my father and thus I joined South Asia Human Right Documentation Centre as a volunteer. For this work, I got some money that sustained me.

But now you are considered as one of the noted human rights activists of the country. Could you give me a brief account of some of landmarks of your journey, including your close association with Irom Sharmila?

Apart from gaining experience and skill at South Asian Human Rights Documentation Centre, I got the first major exposure in 1996 when I had an opportunity to travel to Geneva for attending a three-month training course. During the course, I learnt a great deal about international law, and human rights. Next year in 1997, Manipur witnessed huge state repression, which angered people a lot. It was then that I started documenting the cases of human rights violations in more precise and organized manner. That was how my contribution became central. In 1999, Human Rights Alert was founded with an aim to systematically documenting and exposing the matter at the national and international platforms. In the year 2000, we conducted an independent people’s commission of inquiry into the prolonged impact of AFSPA on the people, which the Supreme Court completely ignored in its ruling that upheld AFSPA. We, thus, invited former Justice H. Suresh of the Bombay High Court, to this inquiry in Manipur, where he made two very important points. Firstly, irrespective of what the Supreme Court said – a sanction to kill can never be constitutional. Secondly, he found that the dos and don’ts regulating power were followed more in breach than in compliance; in practices the do-s have become don’ts and the don’ts have become do-s. Irom Sharmila was then a volunteer in this inquiry and she was the product of this campaign. A week after the completion of this inquiry in 2000, there was a massacre, called Malom Massacre, on November 2, 2000, in which 10 civilians were killed by Assam Riffles. This crackdown by the government was perhaps aimed at arresting mass mobilisation of people. Afterwards, curfew was clamped. In the midst of this, Sharmila came to my house and said that she was going to conduct a hunger strike. Though she got sensitised about the ills of AFSPA during her association with us, we never expected her to take such a huge burden on her shoulder.

Irom Sharmila

Could you speak more about how Irom Sharmila and the campaign against the removal of AFSPA became such a big issue?

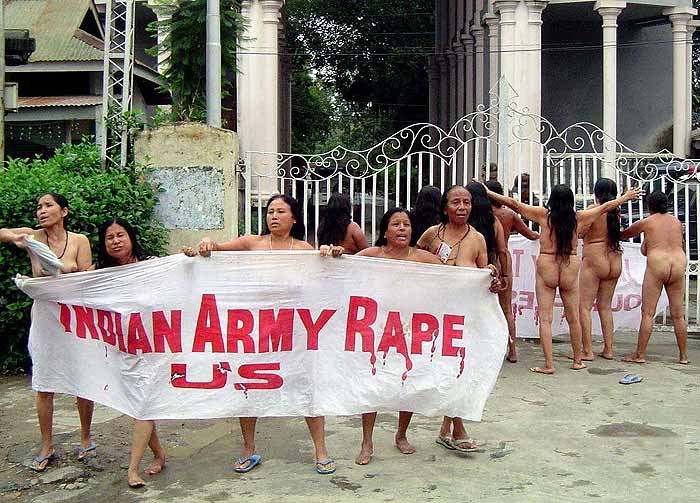

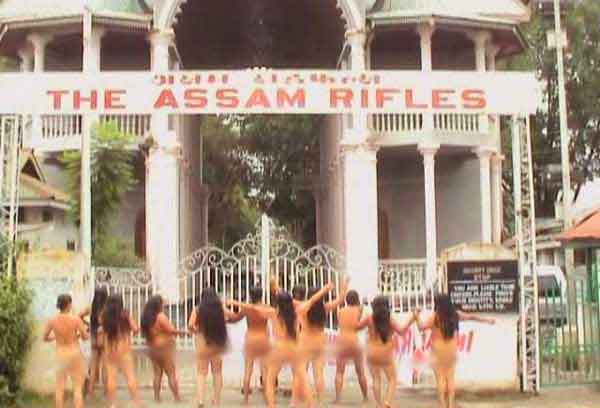

As Irom Sharmila decided to go for a hunger strike, I asked her to demand a judicial inquiry. But she said that she would be asking not less than removal of AFSPA. Given that, we decided to support her and so we took her near Malom, the place where massacre had taken place. In a village near Malom, Sharmila began her hunger strike. Next day on November 6, 2000, she was arrested and charged with an attempt to commit suicide. As she was almost collapsing, the act of forced nasal feeding started on November 21. Meanwhile, we started mobilising support for her hunger strike, which was rather spontaneous than planned. Another important incident was that of Thangjam Manorama rape case, which took place in 2004, as she was taken out of her home by the military forces and was raped, torturerd and found dead on the next day morning, with multiple injuries on her body. This gruesome killing was done with a complete disregard of any civility and people felt very angry about it.

As a result, twelve mothers protested before the Army and for two months Manipur remained ungoverned. In the wake of people’s anger, the Prime Minister met civil society members and assured them that AFSPA would be replaced by a more humane law. Afterwards, the Jeevan Reddy Committee was set up. The Reddy Committee Report, after having visited all the seven states of North-East and met people and officers, concluded that AFSPA should be repealed. The report, though submitted on June 5, 2005, was not disclosed to people for a very long time. In October, 2006 when Sharmila was released for a few days, we put her on a flight and flew to Delhi where she sat on a hunger strike at Jantar Mantar. Her hunger strike in Delhi was very important in a sense that it brought the story out of Manipur and then national media took interest in this issue. Meanwhile, we were also seeking an appointment with then Home Minister Shivraj Patil but Patil put a condition that he could only meet us when we dropped the demand to repeal AFSPA. Placed in such a difficult situation, we were willing to persuade Sharmila to accept medical attention, but not to break her hunger strike, if the Centre released the report of Jeevan Reddy Committee. We went and tried to negotiate with the Home Minister in a meeting but Patil said that he would not go beyond allowing his emissary to read out before Sharmila a certain section of the Reddy report. But even that gesture was with the conditionality put by the Home Minister that she had to drop her hunger strike. Given the unwillingness of the Home Minister to accept our demand, our delegation refused to accept his proposal and thus the negotiation broke down and Sharmila was later arrested.

Interestingly, two days after she was arrested, the Reddy report was published in The Hindu and the report was given to us by a senior Hindu journalist. The Hindu also uploaded the report on its website and thus we were able to circulate it widely. Yet another success came in 2007, when the UN Committee on Elimination of Racial Discrimination in Geneva discussed the findings of Jeevan Reddy Committee, in its exclusive report on India. We also went to Geneva as a NGO participants and briefed the UN experts about human rights violation with the help of the Reddy report. As a result, for the first time the UN panel stamped AFSPA as a racist law. Since India is a signatory of International Convention on Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the UN has every right to demand nullification of racial laws within one year. In February 2007, the Government of India was urged to repeal AFSPA. It was also asked to report to the UN about the compliance of Reddy report in one year by February 2008. Despite five reminders, the Government has not yet reported to the panel. According to the press, when P. Chidambaram was the Home Minister, there was a meeting among the Home, External Affairs, and Defence Ministries and the PMO [Prime Minister’s Office] over the possible amendment of AFSPA. But it is learnt that the Defence Ministry had opposed any such move.

You have been documenting human rights violations in Manipur for a long time. What has been the situation of Manipur? Has it improved or does it still remain a violence-ridden state?

From 2004 to 2007, following mothers’ protest, there were series of military operations in Manipur including Operation Tornado, Operation Somtal-I & II, and Operation Loktak. The period of 2007, 2008 and 2009 was particularly bad because the Army and Manipur Police commandos were following Punjab model of annihilation. Extra-judicial killings were rampant. Every day people died and innocent civilians were killed. Worse still, incentives were given for such murders. In other words, there was a well-placed environment or a vicious cycle, under which innocents were targeted. In 2009, the Home Minister P Chidambaram came to Manipur but we were not given a chance to meet him. Thus, we went to media and said that the approach of the Government worked to maintain trouble and conflict in the region instead of resolving the issue.

What is important to note here is that the worst victims have been women, most of them being widows. Due to continuing violence, women have been completely traumatised. Their lives have been almost finished. During our documentation exercise, we saw their lives closely. Besides, we held a meeting with them where these widows spoke about their sufferings and we all cried and ate together. Later, everybody felt relieved. Since then we have regularly held such meetings. Afterwards, we also started identifying their needs. We found that they were facing several problems related to inheritance and finance. Thus, we started a self-help group with very little money but it gave them some relief. Meanwhile, the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, visited India and we prepared a comprehensive memorandum, putting together 1528 extrajudicial cases. We went to Gauhati to meet the UN Rapporteur, which attracted a lot of media coverage. As a result, the Home Minister was very angry, as reported by The Telegraph, Kolkata. The speculation was rife that such human rights groups were funded by international agencies to malign Indian’s image. Undeterred by such rumours, we later published this report in a book as we had nothing to hide. I gave a copy of report to senior advocate of Supreme Court, Colin Gonsalves, and he suggested that a PIL should be filed in the Supreme Court. Initially, the widows were against filing the PIL, because they feared further harassment that might follow, but we persuaded them. Thus, they were the first petitioners and we became the second petitioners. While the state council in the Supreme Court alleged that we were supported to harm the strategic interests of India, Colin argued passionately in our defense. Eventually, the Supreme Court gave an order that every life in this country is precious, constituting a commission headed by Justice Santosh Hegde. The Hegde Commission submitted its report to the Supreme Court in March, 2013 and on April 4 the report was opened in the Court. The report concluded that all the seven people, killed in all the six cases, had no established criminal records. The Justice Santosh Hegde’s report demolished the myth that the army is above laws and accountability. Following this, we demanded the beginning of criminal prosecution on these six cases, but the Supreme Court is still shying away from this and remaining silent. Thus, we are mobilising public opinion. Ironically, during the last election campaign, the Manipur state BJP made a promise that if it came to power it would repeal AFSPA. But it was more a poll gimmick as the BJP wanted to cash in on peoples’ sentiments for electoral gains. Similarly, when the Congress was out of power, it promised to repeal AFSPA but when it was in power, it defended the draconian law. P. Chidambaram, who had earlier opposed scraping AFSPA, recently called it an obnoxious law. Amid all this, there is one good thing: killings have been drastically reduced in Manipur since 2009. For example, there were only two cases of extrajudicial killings in 2013, compared to 500 such cases in 2009.

You said a few years back that ‘if the AFSPA is not withdrawn in Manipur and other places, 10 years down the line military brutalities will spread across the country’. Do you see any positive change from the Government in the direction of repealing this draconian law?

When AFSPA was being enacted in Parliament in 1958, one M.P. Mohanty vehemently opposed this. He said that AFSPA was ultra virus as the law would enable the central government to deploy its forces in a state without taking its consent. According to him, such a step could be taken only after declaration of the state of emergency. But at that time G.B. Pant tried to give the House an assurance that such measures were temporarily taken and they were being introduced in the disturbed regions. But contrary to such assurance, the ambit of AFSPA has been covering more and more regions over the decades. For example, Lushai region [now Mizoram] was put under AFSPA in the 1960s; similarly Tripura in 1970, Manipur valley and Brahmputra Valley in the 1980s and Kashmir in the 1990s. Even the so-called Red Corridor in central and tribal regions of India was brought under AFSPA-like draconian laws. Militarisation in India has not been reversed but in fact increasing.

When AFSPA was being enacted in Parliament in 1958, one M.P. Mohanty vehemently opposed this. He said that AFSPA was ultra virus as the law would enable the central government to deploy its forces in a state without taking its consent. According to him, such a step could be taken only after declaration of the state of emergency. But at that time G.B. Pant tried to give the House an assurance that such measures were temporarily taken and they were being introduced in the disturbed regions. But contrary to such assurance, the ambit of AFSPA has been covering more and more regions over the decades. For example, Lushai region [now Mizoram] was put under AFSPA in the 1960s; similarly Tripura in 1970, Manipur valley and Brahmputra Valley in the 1980s and Kashmir in the 1990s. Even the so-called Red Corridor in central and tribal regions of India was brought under AFSPA-like draconian laws. Militarisation in India has not been reversed but in fact increasing.

You have also expressed concern about the mega developmental projects for human rights violations, ecological damages and above all demographical changes, which are being carried out by Indian Government in North-East states. What are your concerns?

Now the mega dam projects are coming up, which are meant for extracting resources for corporate industries. Plundering of the resources is increasing. Such plundering is going to be a catastrophe for indigenous population. In these so-called developmental projects, the local people have not been consulted. We are not against development but we have every right to ask ‘development for whom’. As I mentioned earlier, all mega dams are serving the interests of corporate giants and they are not targeted to meet the local needs. While the price is being paid by locals, the profits are amassed by corporate forces. A UN-railway project, connecting South Asia, South East Asia and Far Asia, is being planned. It is a big project and corporate India is poised to gain from this. As a scholar of Trinity College argues, connectivity between India and China is going to be the most significant event in history, even bigger than the opening of the Suez Canal. But such developmental projects should be taken with the consultation of locals and not with the corporate forces.

You have recently been in the news as you allegedly made “derogatory” remarks against the Manipur legislators, terming them as “Mithibong Mittambal” (cowards). Yet, you refused to offer an apology. Do you think that you have overstepped the boundaries?

I am happy that they [legislators] have seriously taken my criticism. I just gave my remarks reflecting the public sentiment at the moment and did not overstep. A leader cannot overlook the will of the people. A leader cannot run away from his/her responsibility. Democracy is essentially about deliberation. Contrary to this, these leaders are scuttling the rights of the people.

Your detractors often argue that the issues of human rights in India should not be internationalised but rather be solved within the framework of Indian Constitution as they might be used by imperialist forces or major powers as a bargaining chip. What are your views?

If this criticisms came before the UN Charter was adopted, it would have had some merit, now it is too late in history to take these comments seriously. When a State becomes a member of the UN they have already subscribed to the UN principles and surrendered part of its sovereignty. Only upholding human rights can bring about sustainable peace. Sovereignty cannot be an excuse for justifying human rights violations. If there is injustice anywhere or there is a threat to justice, international solidarity is bound to emerge. If capital can flow so easily, why can’t human rights solidarity?

(Abhay Kumar is pursuing PhD at Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He can be contacted at [email protected])

.

Comments are moderated