300 Years Of Fossil Fuels And Not One Bad Gal:

Peak Oil, Women's History And Everyone's Future

By Sharon Astyk

20 December, 2010

Casaubon's Book

If you haven't seen this video by Richard Heinberg and the Post Carbon Institute, you should. In a lot of ways it is an excellent summary of the history of fossil fuels, entertainingly and creatively done. In some ways, it is extremely valuable as a basic educational piece.

I'm very impressed with the clarity of this video, but it does have an odd gap in it - all of the human history of 300 years of fossil fuels doesn't have a single female person in it - not one. Women are addressed by implication when population is mentioned - but all the little hand-drawn people are men. There is a female figure meant to represent advertising, and a pony-tailed teenager of indeterminate gender with their back to you watching tv, but all the actors, all the movers, all the shakers, all the drivers of our fossil fuel usage are men in this story.

In this version of history, men invent things - the automobile, the oil well, the Haber-Bosch process, alternating current. Men consume things - all the figures with cars and cell phones. Men extract resources - the lumberjack chopping trees, the miner in his coal mine. Some of this is true - most major inventions were inventions of white males, most coal miners and lumberjacks were men. But the story Heinberg tells is both explicitly and by implication a story of male invention, male progress, male consumption, male destruction. If there's a redemption, that seems to be a guy project from the illustrations as well, but that's not much of the video. Most of all, the video operates to write a history of fossil fuel usage that is fully the responsibility - positive and negative - of one half of human society.

Before I go on to my main point, let me quote something I said in my very first public writings on peak oil and women, written back in 2004, before I even had a blog, in an essay "Peak Oil is a Women's Issue" because I've noticed that many people, suspicious of feminist analyses tend to turn off when women's issues are raised and view them as minor and secondary. I think it is quite as relevant to this piece as when I wrote about it so many years ago, and would argue that the failure to see the history of our society as a history of women's acts and women's influence is not at all minor, just as the failure to grapple with those issues has profound implications for the peak oil movement.

Let me be quite explicit here to begin with - when I speak or write about peak oil as a women's issue, I do not mean what many people have taken the term "women's issue" to mean - that is, something that is solely and primarily the interest of women, and therefore irrelevant to men, or a situation where women's interests are in some way in opposition with the interests of men. I mean, instead, that peak oil has not been envisioned or considered seriously as an issue with particular impacts upon and considerations for women, and that women and the men who care about women - any man with a mother, sister, wife, female partner, lover or friend, daughter or any other relationship with women - that is to say, all men and all women - need to think carefully about how women are going to be affected by peak oil. When I call for women to join the peak oil movement, it is not because our interests are different than the interests of the men presently working on that subject, but because without us, those men may not perceive the impact of their actions upon women, or the importance of the female perspective. I have no doubt that men are just as concerned about the fate of their children as women are, that they care as deeply as women do that their mothers not spend their old age in terrible poverty and that their female friends are well educated, free, healthy and safe. What I think women bring to the table is greater consciousness of the impact of peak oil on women's bodies, women's lives and women's goals. But whatever future we envision, it will only be accomplished as a joint and human project

In some ways the absence of women from a 300 year history of ecological destruction could be seen as a good thing and me as rather churlish for mentioning it - after all, other than our presumably passive role of birthin' too many babies, we women are left totally off the hook for the destruction of the earth. (This gap seems to be something detected even by YouTube, which, upon the completion of this video offered me not another Richard Heinberg piece or another piece about peak oil but a video entitled "Why Girls Don't Fart" by someone called "collegehumor" which has, in what I'm sure is a useful revelation about our culture, been viewed more than 10 million times - apparently even YouTube grasps that the real story is that we Chicks are exempt from all bad things!) There are probably plenty of feminists who would laud a narrative in which men were wholly responsible for the predicament in which we presently stand. What kind of crazy woman would want to claim our part in rendering the planet unliveable?

Well, me, actually. The problem with Heinberg's history is that it is not "the history" of fossil fuels in 300 seconds, it is *a* history - a particular kind of history, one focused heavily on individual heroic achievement (specific inventors, generally male and white, who are given more time and attention than those who machined, used and adapted the technologies into daily use) and one that leaves out a large chunk of the explanation for the growth of fossil fuel technologies out of the story - the roles and acts of women. Now it is perfectly reasonable for a very short history to leave things out. But if we have time to observe that Tesla invented alternating current and everyone has a cell phone, we also have time to observe that one of the largest social changes in human history altered conditions in the Global North so that instead of one person in a household using fossil fuels in the public economy - owning a car, supporting the consumer economy now there were two - or two households.

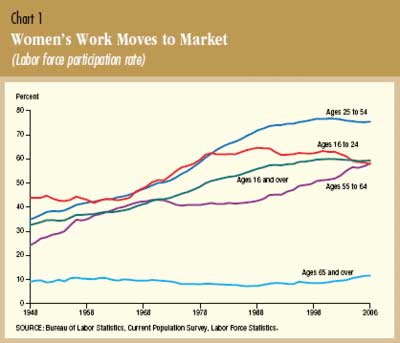

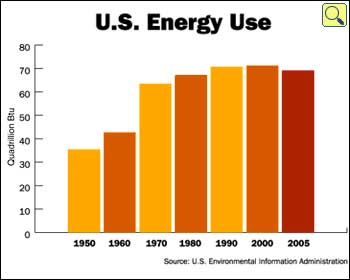

Consider these two graphs:

and:

The consumption of fossil fuels in the US isn't a perfect mirror image of the participation of women in the workforce, but the correlations are substantive and I think it is very hard to deny that women's shift away from domestic work into the public sphere had profound implications for both increased new consumption (cars, professional clothing, social status jockeying) and also for the abandonment of low-input labor that still needed doing (the replacement of the parent at home with the daycare provider to which one must drive, the replacement of home food production with the drive through and packaged food...).

As far as I'm aware, no peak oil analyst has ever really done a good numbers analysis of how much women's move from the informal, domestic economy to the formal, market economy cost us in energy terms - I've never found one and I've looked. But more than the need to use the WWII factory capacity, more than the invention of consumerism, the rise in women in the workforce which rose dramatically in World War II, never declined again to Depression levels (despite the claim that the women's movement didn't start until the 1960s, women's workforce participation remained higher than in the past, as did the divorce rate) and then changed rapidly beginning in the 1960s.

I have a pretty good idea why Heinberg doesn't mention either the rise in the divorce rate that drove up the number of households, creating smaller and smaller units, each with their own stoves and cars and consumer goods, or the rise in women's consumer buying power, the requirements of workforce participation in clothes, outside meals, domestic labor replaced, etc.... There are two reasons. The first is that conventional histories of technology are progressive stories with heavy emphasis on heroic individualism - that is, they tend to be stories about men and single events in industrialization, rather than how technologies are used in daily life. These histories have been challenged but the dominant narrative, the one we all learned in school is about who invented the cotton gin, not about the black slaves that built and repaired them, or the hands that ran them, about who invented the spinning jenny, not the young women factory workers who made use of them. What Heinberg tells here, intentionally or unconsciously, is a conventional history of human technology, one in which our progress is (horribly) inevitable, and in which the only conscious actions are invention - everything else is a tidal wave that leads us in one direction. This is the critical version of the liberal myth of the inevitability of progress, but it takes the same underlying assumptions - that these are natural events in which there are no agents.

The second reason is more fraught - a narrative in which women's entry in the workforce is responsible for our dramatic rise in fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions can look superficially like a tool for those who would prefer that women go back home and come out of the workforce, and would like to blame feminists and feminism for our present ecological disaster. Indeed, if no one has come up with this ideological claim yet, I'm sure it is only a matter of time before someone explains earnestly to me how wimmen's rights are destroying the planet as well as all the other ills routinely attributed to feminism.

That is not, however, a justification for pretending that women's participation in the workforce has nothing to do with our energy consumption however - it is demonstrably true that our move away from the domestic sphere had an enormous impact on our energy usage. We may not like it, but the story of men as environmental bad guys simply doesn't match up to the reality - there are plenty of bad gals for the planet. False narratives are simply never better than true ones, and we all know that not acknowledging the truth won't prevent others from using the story how they choose.

The other problem with avoiding the subject is that it implies that the shallow, empty anti-feminist argument is right - that the only way to tell the truth is to blame women for killing the planet, and that's just nonsense. Feminism has never been one thing, and in the early days of American 2nd wave feminism, it was a lot less one thing than it is now - there were powerful debates about what kind of social changes women actually wanted. What happened, however, was that a particular version of feminism emerged from the debates, successful. As I've argued before in _Depletion and Abundance_ and other places, in fact, the version of feminism that emerged was one that succeeded precisely because it so well served the encompassing model of consumptive market capitalism.

Thus, when early feminists called for men to take up a full half of the domestic labor, and tried to organize collaborative, communal efforts in which domestic labor from cooking to childcare were taken up equitably in group organizations to reduce the total workload, while spreading it more fairly between men and women, what actually happened was an "every household for itself" ethic. With women now working full time while also doing the majority of childcare and housework, what emerged was the abandonment of much domestic labor that once reduced consumption and energy usage, a lot of conflict over what remained, and the replacement of household labor with lower income employees and public economy replacements - ie, instead of the wife one now had a lawn service, the dry cleaner, the daycare center and the stop at the fast food place, and all the corresponding car trips.

The argument is not "the women's movement caused our environmental degradation" - we know historically speaking that social equity can exist in low-input societies, and we know that there is more than one version of feminism. It is my contention that we should be suspicious of this version of feminism's success, rather than laudatory, and that modern industrial feminism has never fully considered the degree to which its assumptions of natural progress are premised on the availability of cheap energy. Instead, what we need to do is ask "If this feminism succeeded not because it was primarily good for women, but instead good for the economy and some women in power, what are the alternatives?"

If feminism (even in collaboration with industrial capitalism) was powerful enough to radically shift the landscape of our economy, doubling and redoubling our energy consumption, and changing definitions of women's roles, it may be that we very much need feminism to change the terms again.

We never seriously questioned the ideology (and it is an ideology) that argued that women and men are more free when they are employed by bosses in the workplace than when they are working for the greater good of their partners and family in the home. It is certainly true that money conveys a measure of freedom - but we have never seriously considered ways in which access to funds might be assured to women in partnership with others - or ways in which men might come to equitably bear the burden of the domestic economy. Some of these have emerged as critiques or as functional alternatives, but overwhelmingly modern feminism has focused heavily on an energy-intensive, environmentally destructive abandonment of the home for the formal economy, rather than a balancing of domestic labor or a reclamation of it. The emphasis on personal choice the primary form of freedom also drove this unconsidered consumption.

Modern industrial feminism (and its partner in crime, modern industrial capitalism) has also uncritically accepted the idea that the progressive narrative in which women can do whatever they want more or less whenever they want is an accomplishment of their will, rather than a result of a fossil-energy intensive infrastructure that includes electric breast pumps, refrigeration, cars, a huge body of people shunted from homes and farms into low paid service economy jobs, the offshoring of things that were once not needed due to available home labor or were made in the home to far away countries, etc.... As I say in _Depletion and Abundance_ you couldn't have come up with a better plan for a consumptive industrial capitalism if we'd spent decades studying the problem. No wonder it was successful.

The deepest failure of modern industrial feminism was that it accepted what a patriarchal society had said about women's work and household and family labor by both genders - that it was meaningless, valueless, drudgery and contemptable. This work, which substituted for fossil labor in a host of ways, and offered in many cases much better alternatives than can be produced by industrial society (Consider, for example, the food - manifestly we ate better when someone was cooking at home) was replaced by fossil energies in a narrative that regarded such a replacement as natural, progressive and inevitable. It built on degradation of women's traditional work and convinced women and men that traditional domestic labor was valueless. instead of men and women sharing domestic labor more equitably, everyone left the home except a few hold-outs, and those paid the price of being told their work was valueless. This abandonment of the home had enormous environmental costs, which we are paying now.

None of this is a new observation - remember, feminism isn't one thing and ecological feminists have been pointing this out for a long time. But what is new is the that the realization that the resources this version of feminism depends on are going to be limited by material realities means that the women's movement needs to grapple - and fast - with the version of feminism we've accepted as normative. This, however is not my primary subject this time

More on track, and equally importantly, the peak oil movement is going to need to grapple with this history. On one level we know it - even at an event as male dominated as an ASPO Conference, I find myself standing with men telling me about how they entering a domestic sphere they have not lived in before, into gardening, food preservation and dealing with the day-to-day realities of living with a lot less consumption of energy. These are guys in suits who make five times as much as I do, asking me earnestly about how to put up their potatoes. In some measure, it is wholly impossible to understand the implications of peak oil without realizing that we're going to be travelling less, having less, staying home more and being able to rely on the formal economy for less. A return to domestic life for both men and women is partly inevitable. The way the recession has played out, driving men out of the workforce may well help with that shift.

It is not, however, sufficient to allow events to drive the way women's participation is understood and used in the peak oil movement. A refusal to grapple with issues of women's history and women's future leads to bad ends - first of all, if we can't identify where the uses of energy derive from, if we return to a passive narrative like the one in the video where male actors invent and then without agency or thought we consume, we will fail to find the places we can make radical change.

When addressing our consumer culture, for example, we must start with women who studies show make or primarily influence 80% of all purchases, including traditionally "male identified" items like cars, tools and building equipment. It is not enough to say we must "stablize the population" and show only pen sketches of little male faces - unless we envision of future in which women are rendered powerless over their own reproductive capacities, such a project involves engaging women.

Moreover, the women's movement was an incredibly powerful cultural shift - industrial capitalism may have subverted feminism, but it didn't create it - women are extraordinarily powerful in shifting the culture, and history suggests this is not a function of cheap energy. If we understand on some level that in order to address our energy consumption, we have to go home again and we need the participation of both men and women to alter our consumer culture, this will have to be formulated, argued and organized as first and second wave feminism themselves were formulated, argued and organized. Only in novels do women go contentedly back to the home as a natural event and return to the good old days complete with legal marital rape and a sixth grade education, and that's not likely to be much of an enticement. Everyone has to go home and the argument must be framed in a way that inspires and engages, revaluing domestic labor, taking the stigma off of traditional "women's work" while also making it the shared territory of men and women.

The beginnings of this cultural shift exist - they exist in the writings on Subsistence by Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen and Maria Mies, in the ecologically informed Global South feminism of Vandana Shiva and Helena Norberg-Hodge, in the ideology of Radical Homemaking of Shannon Hayes and in my own work, and in countless other places. At this point, however, as we can see so clearly from this video, these narratives are marginal - they aren't part of history and they aren't part of the future. Post-Carbon and Heinberg are telling a critical story - but the actors they need to engage, all the hands they want on deck are not engaged, because they aren't part of the tale. That needs to change. If the future depends on a new relationship to the world, to our children, to consumption, to the earth, that's got to be framed, and it can't happen without fifty-one percent of the world's population fully participating - and not as an afterthought.