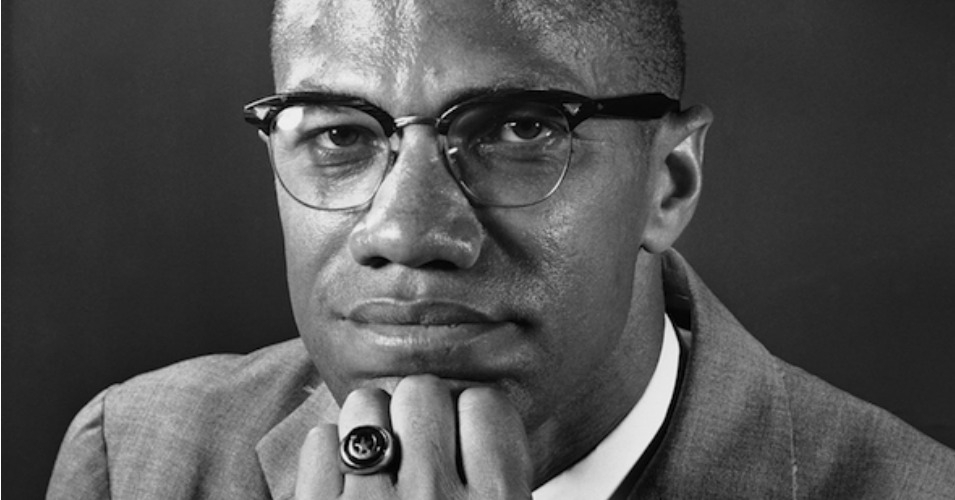

Malcolm X: His Philosophy In The Struggle Against Racism And Injustice

By Douglas Allen

30 September, 2015

Countercurrents.org

Recently we marked the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X (February 21, 1965), and this occasion brought some media focus to his life and significance. This was in contrast to the earlier, U.S., mass media’s stereotyping, vilification, and dismissal of Malcolm X as some hate-filled, violent madman during his lifetime and the overwhelming marginalization and silencing of his message during the past fifty years.

In this article, I’ll attempt to formulate Malcolm X’s philosophy during four stages of his life without providing quotations from Malcolm’s speeches and writings that support these formulations. Before examining Malcolm’s philosophy, I’ll share a very dramatic incident that involved my teaching of Malcolm X.

A Dramatic Challenge and Attack

The mass media’s treatment, usually mistreatment, and later silencing of Malcolm X can be contrasted with what I experiencedearlier, especially as related to students and members of the community. My first full-time faculty position was at Southern Illinois University (1967-1972), which was sometimes described at the time as having the largest number of African-American students of any major integrated university. At the time, SIU had a large Black Studies Program with its own building and with many faculty and course offerings.

At the insistence of African-American students, I finally agreed to offer a philosophy course in Black Philosophy. I structured the course by starting with two key figures: three weeks on the philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr. followed by three weeks on the philosophy of Malcolm X. By comparing and contrasting King and Malcolm, we could examine their analysis of racism, the nature of the self and self-identity, violence and nonviolence, integration and separatism, justice and injustice, and other topics. I found that the class was almost equally divided, with roughly half more sympathetic to Malcolm X and the other half more identifying with King’s philosophy.

One of many, very intense experiences that occurred during the first time I offered Black Philosophy illustrates how some students (and other people of color throughout the U.S. and the world) were relating to Malcolm X. We had completed two weeks on King. At the beginning of the next class, one black student, who at the time identified with the so-called “Black Muslims” of the Nation of Islam, stood up at the front of the class with his “bodyguards” on either side. In a soft-spoken but very dramatic prepared speech, he began as follows: “With due respect, everything we have done in this class is BS (bullshit).” He concluded his speech with this challenge: “What we should be studying is the only issue for black people today. What is the true religion for black people, Christianity, the white man’s slave religion, or Islam, the religion of black liberation?”

The students, black and white, looked at me. You could have heard a pin drop. It turned out that I was very lucky in avoiding what could have easily become a disastrous consequence for the rest of the semester. On the one hand, if I had used my faculty position of authority to ignore or disrespect this black student’s challenge, really more of an attack, I would have lost the respect of many students. This would have confirmed their view of oppressive white power being imposed on blacks. On the other hand, if I had responded in the way that some of the white liberal faculty, driven by guilt and concern about white racism, uncritically accepted or enthusiastically supported whatever black students said in class, I also would have lost the respect of many students. Some might have felt a temporary victory, standing up with dignity and telling the white man off, but more would have felt I had been guilty of a cop-out in not responding to the black student’s challenge adequately.

Knowing that this student and his friends admired Malcolm X, I responded that we would be examining Malcolm’s writings on Islam and Christianity, but to reduce Malcolm’s philosophy to that one topic would be to do him an injustice. Malcolm X was much more complex and insightful than that, so that I also felt an obligation to examine what he wrote about violence and nonviolence, separatism and integration, black nationalism, economics, politics, culture, and other significant topics. I then invited this student and others to share their views on Malcolm X in the coming weeks, even welcoming class presentations, but only if they took this seriously, as I did, and took the time to prepare carefully so that their presentations made critical contributions with philosophical relevance and significance.

As an aside, the students who organized the challenge in class were very satisfied. They had had the courage to stand up and speak in their own voice. The particular black student and I became very good friends. He changed his name to a Muslim name, asked to present on Malcolm X in the following years, and later rejected the Nation of Islam while remaining a Muslim. He recently wrote a book on Black Muslims in the U.S.

Malcolm’s Early Philosophy

By “Malcolm’s early philosophy,” I include what became Malcolm Little’s philosophy during the time he lived in Michigan, later moved to Boston and New York City, went to prison, and before he became a member of the Nation of Islam. This can be described as the Hustler’s Philosophy that intends to relate to the hustler’s hard world in ways that are practical, realistic, and avoid all dangerous illusions and sentimentality.

In Malcolm’s hustler philosophy, one views human beings and the world as ruled by the “Law of the Jungle.” Everything is a hustle. Always look for the material gain, the payoff. The essence of this hustle concept is self-gain. There is a hierarchy with the hustler at the top. The hustler makes money primarily on whom one knows, on one’s connections, through activities that are usually illegal. The pimp and others are lower in the hierarchy. There is a general practice: be hard, be cool, be secretive, don’t trust, and don’t give anyone any unwarranted breaks. This means assuming a stoic attitude in which one is willing to kill point blank, if necessary, without blinking an eye. In the hustler’s philosophy, there is a common foe: police and informers. There is also a common friend: one’s self.

In short, Malcolm Little’s philosophy is atomistic and individualistic with the focus on one’s own separate self as driven by self-gain. This necessitates adopting means, when necessary, that are violent, dishonest, secretive, and illegal. This philosophy is amoral, with no place for ethics and moral values that show weakness and make one vulnerable. It has no place for religious values and concerns that are completely irrelevant in the hustler’s philosophy. And it has no place for any social philosophy and commitment to overcoming racism and injustice.

Perhaps startling and revealing, my students and I began to realize that of all of Malcolm’s philosophies, this early Hustler’s Philosophy is closest to the philosophy and practices of individuals, institutions, and policies of the white, capitalist, power elite. The economic leaders who run huge corporations and Wall Street financial institutions, the political and military leaders, the heads of the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency, etc., adopt a view of a world ruled by the Law of the Jungle in which they must unsentimentally and amorally calculate self-gain and material payoff. In other words, when one demystifies self-serving ideologies and justifications, it is clear that the dominant, U.S., economic, political, and military amoral and power-driven polices and values are closest to Malcolm’s hustler philosophy. They have little to do with real opposition to racism and injustice.

Malcolm X’s Philosophy as a Member of the Nation of Islam

During his six years in prison (1946-1952), Malcolm becomes familiar with and then identifies with the Nation of Islam led by “the Honorable Elijah Muhammad.” He rejects his white Christian name, becomes Malcolm X (the X standing for his unknown, ancestral, African name), and embraces the name el-Hajj Malik el-Shabbaz. For more than ten years, he develops his philosophy as a so-called “Black Muslim,” becoming the most charismatic leader in the Nation of Islam.

The Nation of Islam identifies itself as Islamic, with members who are Muslims (“Black Muslims”), but it is a particular U.S. black creation and institution. It contains a philosophy, values, and practices that are peculiar to a U.S. black context and cannot be found in Sunni, Shia, Sufi, and other Islamic denominations. Created on July 4, 1930 by Wallace D. Farr Muhammad in Detroit, the Nation of Islam was most defined by its leader Elijah Muhammad, who was based in Chicago.

What appeals to Malcolm is the Nation’s clear message and rigid conservative code of conduct aimed at black spiritual, mental, social, and economic improvement. Elijah Muhammad teaches that “the white man is the devil” and that blacks are brainwashed. Adopting his Islamic faith position that focuses on the complete separation of the races, justified by an idiosyncratic mythology with its creation narratives and mythic views of history, Elijah Muhammad teaches black separatism, black self-reliance, small-scale black capitalism, and ultimately the return of African Americans to Africa.

Malcolm X is unequivocal in upholding the need for complete black separatism. He provides both religious and historical arguments. Using his faith commitment, with Islam the religion of black liberation and with specific Nation of Islam accounts, he contends that separation of the races is the divine way. If whites do not allow for black separatism, God (Allah) will bring His wrath down on the white race. Providing historical evidence from slavery and racism in this nation and from the contemporary oppression of people of color throughout the world, Malcolm contends that blacks always find that it is racist whites that are oppressing them and treating them unjustly. Whites are the common enemy. Since whites have no real desire for an integrated society and are incapable of treating black as equals, separation of the races is the only solution.

In this philosophy of Black Muslim separatism, Malcolm no longer upholds his hustler’s atomistic and individualistic philosophy of self-gain. He now adopts a philosophy of unity and solidarity, but this is completely defined by the primary category of race. Since so-called Negroes can now see through the brainwashing, they can unite based on recognizing whites as the common enemy and the need for separate black identity and development.

Malcolm X identifies this philosophy of black separatism with Black Nationalism and Black Revolution. He submits that nationalism means getting land, the basis of independence, freedom, justice, and equality. What blacks have experienced in this nation is white nationalism. Since blacks do not have their own land, they are dependent on whites and are treated unjustly and unequally. He submits that real revolution, not the phony so-called Negro revolution of King and the Civil Rights Movement, is based on land. The American Revolution was about whites here getting their own land. Therefore, if whites are the enemy, nationalism is getting one’s own land, and revolution is based on land, Black Revolution involves Black Nationalism involves Black Separatism.

The only long-term solution, as taught by Elijah Muhammad, is complete back-to-Africa separation and return to the true black homeland. However, since America will not allow this, the short-term solution is a separate black territory here within the U.S. with just compensation for past slavery and racist exploitation. Then, consistent with the will of Allah and as taught by the Nation of Islam, blacks will become self-reliant in their separate territory and will live independent, developed, spiritual, psychological, economic, and cultural lives.

Malcolm X’s Transitional Philosophy

Although some of Malcolm rethinking begins to develop earlier, this transitional revision of his philosophy is sometimes dated to the period that starts in December 1963, after President Kennedy’s assassination and when Malcolm is silenced and suspended by Elijah Muhammad on December 4. Malcolm publicly announces that he is leaving the Nation of Islam on March 8, 1964 to organize a new movement. This transitional period extends to April 1964 when Malcolm leaves for Mecca and Africa.

One can provide different explanations for Malcolm X’s separation from the Nation of Islam. The usual explanation traces this to Malcolm’s answer to a question about Kennedy’s assassination that this is a case of “the chickens come home to roost.” Malcolm’s comment is consistent with Biblical passages on God’s justice that you reap what you sow and those who live by the sword will die by the sword. However, his comment infuriates Elijah Muhammad who had sent condolences to the Kennedy family and had instructed Nation members not to comment on the assassination.

There are at least three other explanations for the break. First, Malcolm X has become so visible and influential, and this provokes a negative reaction by some Black Muslims who see him as a threat to Elijah Muhammad’s leadership. Second, Malcolm becomes deeply disturbed and disillusioned as he learns of Elijah Muhammad’s extramarital affairs with young Nation women who work for him and with whom he fathers children. Third and most important for Malcolm X’s evolving philosophy, he increasingly feels restricted by the narrow, rigid, conservative philosophy and practices of the Nation of Islam that do not allow him to engage and become a leader in the larger civil rights and human rights movement.

To summarize Malcolm X’s transitional philosophy, he continues to affirm Elijah Muhammad’s position that the only long-range ultimate solution for African Americans is complete separation with the return to Africa. However, this is not the short-term solution, and Malcolm begins to rethink a more adequate philosophy addressing the situation of blacks in the U.S. today. He formulates this as Black Nationalism: the philosophy of political black nationalism (educating blacks to control the politics of their communities), the philosophy of economic black nationalism (educating blacks to invest in and control the economy of their communities), and the philosophy of social black nationalism (educating blacks to eliminate vices and evils by learning about their cultural roots and how to live with dignity and self-respect).

Malcolm X begins to recognize that if black nationalism means “nothing more” than blacks controlling the economic, political, and social and cultural life of their communities, then it is possible to have elements of black nationalism in secular groups, in religious groups that are not Muslim, and in groups opposed to back-to-Africa separatism. In fact, by the time that Malcolm is leaving for Mecca and Africa, he has little interest in focusing on black separatism. In strong contrast to earlier speeches, he is willing to include in his philosophy of black nationalism those who are not black separatists. He asserts that blacks confuse integration or separation, which are methods employed by different African Americans, with the shared true objective: recognition and respect for blacks as human beings with freedom, justice, and equality. Blacks are fighting not for separatism or integration but for rights that go far beyond civil rights and are human rights.

Malcolm X’s Philosophy After Mecca and Africa

Malcolm X leaves for Mecca and Africa on April 13, 1964, and he holds a press conference on his return on May 21. His Muslim spiritual pilgrimage to the holiest site in Mecca, where he completes the Hajj, and his subsequent visit to several African countries, where he has thought-provoking encounters with militant revolutionaries, are full of powerful transformative experiences. At Mecca, he has positive encounters with a wide variety of Muslims from throughout the world, including Muslims who are not black. In Africa, while Malcolm is being tailed and is under U.S. government surveillance, he shares his philosophy of political, economic, and social black nationalism, and an African revolutionary asks Malcolm where that leaves him, since he is not black.

Malcolm’s life, from May 1964 to February 1965, is extremely difficult, chaotic, and stressful and includes threats on his and his family’s life. Malcolm no longer has the rigid organizational structure, enforced rules, and organized forceful protection of the Nation of Islam. Nevertheless, during this period, Malcolm is extremely active as he founds his nonreligious Organization of Afro-American Unity in June 1964 and gives frequent interviews and speeches right up to the day of his assassination.

In summary, Malcolm X no longer seems to identify with the separatism of the Nation of Islam, even as an ultimate long-term solution. And in his short-term philosophical approach, he is questioning his formulations of black nationalism. As he notes in his last speeches and interviews, he is no longer referring to black nationalism, but he is unsure what to call his philosophy.

Citing examples of immigrant groups that came to the U.S., Malcolm X begins to rethink whether blacks in the U.S. could “migrate” or reach out to Africa in cultural, psychological, and philosophical ways while remaining here physically. This could provide a sense of roots or foundations that blacks will never find in white America and for developing a “spiritual bond” that will be mutually beneficial to both Africans and African Americans.

During his last nine months, Malcolm X’s speeches and writings express an unfinished philosophical project with an openness reaching out to new, necessary, developing reformulations that are cut short by his assassination. For his critics, especially in the Nation of Islam, Malcolm has become unglued, totally confused, and is a dangerous and even treacherous madman. He unappreciatively and arrogantly rejects the teachings and imposed rules of Elijah Muhammad on Allah’s divine plan, the need for black separatism, and the restricted proper focus and conduct for Black Muslims. For his supporters and admirers, Malcolm is rejecting or revising previous, narrow, and inadequate formulations, is indeed struggling but is seeing things much more clearly, and is in the process of broadening and deepening his philosophy and practices.

In my interpretation, Malcolm X is broadening and deepening his thinking and developing his philosophy in both religious and nonreligious ways. Religiously, Malcolm affirms that he is a Muslim, but not a member of the Nation of Islam (a “Black Muslim”). He realizes that the Nation of Islam is not traditional Islam. He also realizes that 99% of Muslims do not accept Elijah Muhammad’s highly idiosyncratic teachings of creation stories and other theological and historical narratives with whites portrayed as white devils and with the unqualified need for complete separation and restricted focus on the internal black community.

Through his experience of the Hajj at Mecca and other encounters, Malcolm X is rethinking his formulations of Islam while upholding his view that it is a philosophy of empowerment and liberation for African Americans. His Islam is not racially defined in rigid ways and can include Muslims who are not black. His reformulated, more inclusive Islam has room for Muslims who are not black separatists and for positive relations with other progressive religious and nonreligious people who are not Muslims.

In larger economic, political, social, and cultural concerns, Malcolm X is radically broadening and deepening his philosophical formulations. It is true that he refers to white colonial domination in his 1963 “Message to the Grass Roots,” when providing historical support for why blacks can unite around a common enemy, but his political and economic thinking are very undeveloped. Now through his transformative encounters in Africa and later experiences, he begins to rethink his philosophical formulations. This is most evident in his struggles with his views of black nationalism.

In my interpretation, Malcolm increasingly realizes that even his transitional reformulations of a broader short-term black nationalism are too narrow and inadequate for black freedom, justice, and equality. If one wants to understand the situation of African Americans, it is necessary to understand the larger economic, political, militaristic, psychological, social, and cultural systems and conditionings that shape the life of the internal black community. And this necessitates an analysis that understands and resists global racist and unjust systems of exploitation, violence, and domination and expresses solidarity with revolutionary and other progressive forces struggling for freedom, justice, and equality.

Therefore, in his confusion as to what to call his evolving philosophy, Malcolm X does not reject major features of his black nationalism, such as the need for African Americans to become empowered to control the economics, politics, and culture of their own communities, even if his black nationalist formulations need to be broadened and deepened. What he realizes is that such a reformulated black nationalism is necessary but not sufficient. Black nationalism by itself, with its focus on black community life, is inadequate. What is required is black nationalism plus a much broader and deeper revolutionary philosophy that recognizes the need for getting at root causes and struggles for radical structural and systemic changes necessary for freedom, justice, equality, and real substantial human rights.

Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.

It has been commonplace for some interpreters to assert that King and Malcolm, who only met once, are moving closer late in their lives. It is claimed that if they had not been assassinated, each at the age of 39, they would have been able to unite in shared struggles for freedom, justice, and equality.

It is important not to gloss over significant differences in their philosophies, even in their last years. For example, Malcolm X, while he revises his formulations of black separatism, never endorses King’s absolute commitment to integration. To provide another significant difference, while largely refraining from his earlier forceful attacks on black proponents of nonviolence, Malcolm never endorses King’s absolute commitment to nonviolence and upholds a philosophy of “by any means necessary.”

Nevertheless, it is certainly true that Malcolm X’s philosophy and King’s philosophy, so widely apart and oppositional in earlier formulations, are increasingly moving closer as each broadens, deepens, and radicalizes his formulations. King’s earlier focus on opposing segregation in the South and promoting civil rights could be supported or tolerated by much of the U.S. power elite. However, in his last years, King formulates a more radical philosophy of integration focusing on real integrated living that necessitates the sharing of power and a radically restructured economic system. He finally comes out strongly against the Vietnam War. He is moving in the direction of what looks like democratic socialism. Going beyond his earlier formulations of segregation, racism, and violence, he begins to provide more of a class analysis of power, as seen in his Poor People’s Campaign and demands for economic justice. He begins to formulate a radical philosophy that opposes capitalist materialism that puts profits before people’s real needs, opposes U.S. militarism, and opposes an unjust global imperialism. Such a King is increasingly a threat to the U.S. power structure.

Similarly, Malcolm X’s earlier hustler philosophy and his later Black Muslim philosophy could be portrayed in racially stereotypical and marginalized ways as so radically unlike and inferior to the values of the dominant white power structure. But they really pose no serious threat to the interests and power of the U.S. elite. However, in his last periods, Malcolm moves away from the black capitalism of the Nation of Islam. He begins to develop an anti-capitalist analysis of economics at home and globally. Through his encounters with revolutionaries, socialists, and others, his philosophical rethinking expresses the need to get at root causes and bring about a radical restructuring of our economic, political, social, cultural, and other systemic structures and relations. Such a Malcolm X, as seen in measures taken by the C.I.A. and U.S. Government, is increasingly seen as a threat to the U.S. power structure.

Malcolm X and Socialism

Late in his life Malcolm X becomes increasingly anti-capitalist. This anti-capitalism is expressed in two ways. First, having focused for over a decade on racism, Malcolm begins to link capitalism and racism. “You can’t have capitalism without racism.” Second, he begins to focus on how capitalism is necessarily exploitative, “like a vulture and can only suck the blood of the helpless.” Since the exploitative “system of capitalism needs some blood to suck” and people and nations will increasingly free themselves, capitalism in time “will collapse completely.”

Malcolm X’s anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism, and growing interest in socialism can be understood in terms of the local, national, and international contexts within which he was living. In the late 1840s, Karl Marx wrote that revolution was in the air, and he supported anti-capitalist revolutionary struggles, even while recognizing that the economic and historical conditions and relations were not ripe for successful revolution. Similarly, by 1964 and early 1965, revolution is very much in the air in black and other radical anti-capitalist and often socialist movements in the U.S. and throughout the world.

Malcolm confesses that he is open-minded, flexible, but unsure of what to call his economic, political, and social philosophy. He now writes that the revolutionary struggles against exploitation and oppression cannot be restricted to local communities or to the U.S. but must be viewed globally. He writes that the remarkable anti-colonial and anti-imperialist leaders and movements throughout Africa and elsewhere all seem to uphold socialist philosophies. In addition, Malcolm writes that when he finds a person who is not a racist, this person is usually a socialist, upholding a philosophy of socialism.

Probably much of the view that Malcolm X, late in his life, becomes a revolutionary anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, and pro-socialist can be related to George Breitman’s The Last Year of Malcolm X: The Evolution of a Revolutionary (1967). Breitman is a dedicated Trotskyist, a founding member of the U.S. Socialist Workers Party in 1937 and editor of the SWP’s weekly newspaper, The Militant. As an aside, amidst internal factionalism, he is expelled from the SWP in 1984, two years before his death. As a committed Trotskyist and formulating the Party’s position during the last years of Malcolm’s life, Breitman knows that nationalism can be very reactionary, but he supports revolutionary nationalist movements taking place throughout the world. He believes that such revolutionary nationalisms will evolve into a new, more adequate socialism. Therefore, as shaped by his own framework, Breitman interprets, usually in convincing terms, Malcolm X’s revolutionary philosophy as pro-socialist and evolving toward a more revolutionary socialism.

What is clear is that Malcolm X, even at the end of his life, is not a Marxist. In my own view, there are at least two main reasons for such a conclusion. First, Malcolm, although he repeatedly emphasizes the need to learn the lessons of history, does not place a major focus on the political economy of historical materialism. Even with his anti-capitalism, he does not focus on analyzing the capitalist mode of production, relations of production as class relations, and the material basis for revolutionary change. Second, although he increasingly focuses on capitalist exploitation and oppression, Malcolm does not emphasize class analysis in any Marxist way. It is true that he begins to express the need for multiracial alliances, that include militant whites dissatisfied with racism, capitalism, and imperialism, but he does not focus on white workers. Unlike most socialist Marxists, he does not address working-class solidarity and unity as part of his evolving revolutionary philosophy.

It is entirely possible that Malcolm would have moved in a Marxist direction. With a modified Islamic position and perhaps consistent with some liberation theology, he might have moved toward a Marxist analysis in making sense of the economics and history of racism and exploitation. And it is significant that Malcolm, even while still a member of the Nation of Islam, shows a remarkable class consciousness, as in his famous distinction between “the house Negro,” with his major examples of King and other Negro preachers, and “the field Negro.” With his class background and consciousness, Malcolm makes clear oppositional distinctions in antagonistic class relations and identifies himself as a field Negro in solidarity with the exploited and oppressed black masses. Malcolm might have developed this class analysis in a more Marxist direction.

So where does this leave us with regard to Malcolm X and socialism? As has been seen, Malcolm X, late in his life, is rejecting many of his earlier positions, is broadening and deepening his analysis, and is unsure of what to call his new evolving revolutionary philosophy. He continues to develop his long-standing analysis of racism, becomes strongly anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist, and increasingly develops sympathy for and identification with socialism.

In terms of later contextualization, it seems clear that Malcolm X, in the decade after his murder, would have become increasingly radicalized in his opposition to capitalism and imperialism and his support for socialism. We can only speculate on how Malcolm, so intelligent and courageous and open to new experiences, would have related to the economic, political, and violent undermining and destruction of black radical groups and individuals in the U.S. We can only speculate on how he would have related to the neo-colonial, neo-liberal, and violent undermining, marginalization, corruption, and violent overthrow and assassination of the remarkable anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, pro-socialist, national, revolutionary leaders and movements throughout Africa and other parts of the world.

All we can say is that Malcolm X, especially in 1964 and early 1965, is becoming more and more attracted to socialism. His socialism in his evolving revolutionary philosophy is undeveloped, but he leaves us with possibilities and directions for more developed formulations.

Douglas Allen is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Maine. He has been a peace and social justice activist since the 1960’s.

Comments are moderated