Science Is Not A Sports Race With Winners And Losers: Heinrich Rohrer

By Kourosh Ziabari

23 October, 2012

Countercurrents.org

Doing interviews with Nobel Prize laureates in different fields, whether in chemistry, physics or medicine, especially those laureates who were awarded the prestigious prize in the past decades, is a great opportunity to explore the history of science and get acquainted with the truths and realities regarding the groundbreaking achievements which were made in the sphere of science when many of us were still very young and unaware about what the world's greatest scholars and researchers were doing to pay homage to humanity and improve our understanding of the planet and universe we live in.

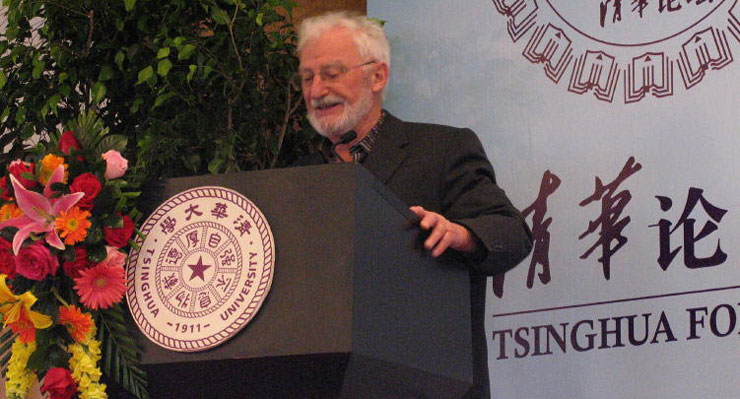

Now, we return to more than 26 years ago to interview a Swiss scientist who won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physics for his important designing and inventing the scanning tunneling microscope (STM) which is used to imaging surfaces at atomic level. Prof. Heinrich Rohrer, born in the beautiful city of St. Gallen in the northwestern part of Switzerland , shared half of the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physics with his colleague Gerd Binnig. The other half was awarded to Ernst Ruska, the German physicist who passed away in 1988.

Born on June 6, 1933 , Prof. Heinrich Rohrer was awarded the Nobel Prize since his invention, according to the Nobel committee, opened up "entirely new fields...for the study of the structure of matter."

Dr. Rohrer studied at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich , where he received his bachelor's degree in 1955 and his doctorate degree in 1960. In 1963, he joined the IBM Research Laboratory in Rüschlikon and worked under the supervision of Ambros Speiser. He worked on nuclear magnetic resonance at the University of California , Santa Barbara in 1974.

In a 2008 interview with the Nobel Foundation website, Rohrer said, "young people are not yet biased in their mind. They are not completely taken by their expert opinions. Expert opinions have a difficulty to go beyond of what they know. When you start in a new field, from the point of view of a scientist, you certainly are 20 years younger, because in the new field you're not yet biased and you look at certain things a little bit more relaxed and a little bit more open. "

Rohrer married Rose-Marie Egger in 1961 and went to France and Rotterdam for honeymoon.

What follows is the text of our exclusive interview with Heinrich Rohrer which was published in Persian in Iran 's oldest scientific publication, Daneshmand magazine earlier this year, and is being published in English for the first time on CounterCurrents.

Kourosh Ziabari: Please tell us about your first engagement with science. What made you interested in science in general and physics in particular? How did you maintain this interest in long run?

Heinrich Rohrer: I was a reasonably good in school, both the first 9 years in a countryside school and afterward in high school in Zurich . Mathematics, science and Latin and Greek were my favorites, I did less great in humanities and modern languages. Finally, I gave up the romantic touch of old languages, decided for a technical career, and enrolled in The Mathematics and Physics department at the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zürich. After a year, I felt that Mathematics on the University and higher level was too abstract for me and I decided to continue with Experimental Physics. I was lucky to choose a career which interested me and there was no reason to change. I guess ability and interest are usually very closely linked, otherwise it becomes a catastrophe.

Heinrich Rohrer: I was a reasonably good in school, both the first 9 years in a countryside school and afterward in high school in Zurich . Mathematics, science and Latin and Greek were my favorites, I did less great in humanities and modern languages. Finally, I gave up the romantic touch of old languages, decided for a technical career, and enrolled in The Mathematics and Physics department at the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zürich. After a year, I felt that Mathematics on the University and higher level was too abstract for me and I decided to continue with Experimental Physics. I was lucky to choose a career which interested me and there was no reason to change. I guess ability and interest are usually very closely linked, otherwise it becomes a catastrophe.

Kourosh Ziabari: You have had the precious opportunity to work under the supervision

of Prof. Wolfgang Pauli who was a Nobel Prize laureate himself. What did you learn from him? How did he contribute to your future success as a Nobel Prize laureate? Overall, how was the experience of working with him?

Heinrich Roherer: My only contact with Wolfgang Pauli was the theory courses which he gave for the undergraduates. Most influence on me had Joergen Lykke Olsen as practical thesis advisor and young "Oberassistent" - not even associate professor then. His determined honesty and gentlemen politeness - a Dane who got his physics education in Oxford - were unique, a very gifted and clever experimentalist without putting himself into the center. He did not interfere with one's work except when things did not work well with something like: "could one not do it this way".

Kourosh Ziabari: Please tell us about the academic environment of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. Many great scientists and Nobel Prize laureates had studied there and the institute is a prominent European academic venue. How was the scientific atmosphere of ETH? What about the level of knowledge and scientific credibility of the tutors and instructors?

Heinrich Rohrer: The admission criteria were the same as for the 6 cantonal Universities Geneva , Lausanne Neuchatel, Bern , Basel , and Zurich . However, the study plan was strictly enforced both in time and subjects - no "eternal" students -. Exceptions were made for service in the Swiss army and similar. The dropout rate was high, at my time more than 1/3 in the first two years. Wofgang Pauli, then department head of Physics and Mathematics greeted us Newcomers with the words: "if anybody of you thinks he too bright to have to study very hard then he better leaves now". And Pauli was an intellectual genius and worked always hard, but also enjoyed the sweeter sides of life.

Kourosh Ziabari: Your invention of scanning tunneling microscope won you the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986. This device is used for imaging surfaces at the atomic level. Would you please give more details on the applications of this microscope and its uses? What's the significance of imaging surfaces at an atomic level?

Heinrich Rohrer: First let me mention that a Nobel Prize is not won, it is give and received. Science is not a sports race with winners and losers. Chemical and physical processes take place on an atomic or molecular scale and many important one on surfaces e.g. catalysis, growth. So you have to able to observe them in order to understand them. Of particular interest is the behavior at impurities and other nano-local irregularities, where STM and other local probe instruments mentioned below are the only reasonably applicable tools. The STM and alike are not only imaging instruments but find more and more use as local surface modification tools.

Kourosh Ziabari: During your honeymoon trip to the United States, you conducted some studies on thermal conductivity of type-II superconductors and metals. Would you please explain more about these studies and their results?

Heinrich Rohrer: The question is not quite correct. We married a week before leaving for the United States where I assumed a Post-Doc position for two years. Honeymoon trip consisted of a week trip through France to Rotterdam where we boarded on a freighter - that was the cheapest way to get to the USA for a two year stay. Actually, I had to fish the basic military training as a lieutenant of the Swiss mountain infantry. The Post-doc research at Rutgers , the State University of New Jersey, USA, had nothing to do with what I did for my Ph.D thesis. Superconductors of the second kind were a new, fashionable type of Superconductors with a mixed phase consisting of normal and superconducting domains. The mixed phase became evident in the temperature and magnetic field dependence of the thermal conductivity.

Kourosh Ziabari: Based on your invention of STM, many other microscopy techniques were developed such as photon scanning microscopy, scanning tunneling potentiometery and atomic force microscopy. Would you please elaborate more on these achievements? Does your invention enable the scientists to go deeper into STM-related studies and open up new horizons?

Heinrich Rohrer: Which method is used depends on the property in which you are interested. If you want to map out the electric potential, you use scanning tunneling potentiometery. If you work with insulating surfaces you have to take an atomic force microscope. The merit if the invention of the STM that we showed that one can keep something, e.g. the tip of a needle, stable in space with a stability of, say, a thirtieth of an atom diameter.

Kourosh Ziabari: You have described your experience in IBM Research Laboratory in Rüschlikon as enjoyable and fruitful years of your life. What researches did you carry out there? You studied Kondo systems with magnetoresistance in pulsed magnetic fields. Would you please give more details on that?

Heinrich Rohrer: From the magnetoresistance of conductors and semiconductors you can learn about both magnetic and electric properties of these materials, in particular in very high magnetic fields. Very high meant at that time some 250 kOe (or 25 Tesla) which were produced in small coils and pulsed electric currents, say some 20'000 Amp pulses. The Condo effect was a fashionable topic: nonmagnetic metals doped with magnetic impurities, say 1 %, showed an increase in resistance ar low temperatures. After some years I had done what I could do in this field and continued with magnetic phase diagrams, using pulsed high magnetic fields. After some years this brought me into the area of critical phenomena, an upcoming hot topic in science and finally ventured with Gerd Binnig into studying inhomogeneities on a very small scale which brought us to the development of the Scanning Tunneling Microscopy.. I had the freedom at IBM to change my research fields and I took this great opportunity when I had the feeling that I had done in a field what I reasonably could. Changes make it easier to keep an unbiased mind, but it is always a venturous risk to give up an established position in a field and start as a nobody in another one.

Kourosh Ziabari: What's the greatest challenge which the physicists around the world face today? What's the biggest question in physics which you desire to solve and find a solution for?

Heinrich Rohrer: For Physics I cannot tell. Complexity is certainly an area, maybe solving many body problems as elegant as nature does. I guess every scientist is biased by his own research area. For science and technology on the nanometer scale I think of a) growth and fabrication of given nano structures or components at a given nano location for a given function, b) easy and straightforward access to nano interfaces, c) wireless communication and energy supply to Nano systems, I.B. nano robots, and whatever your liking is.

Kourosh Ziabari: You have dedicated most of your life to studying the structure of the molecules, their constituents and the way they interact with each other. What has physics taught you beyond its conventional implications? I mean, what have you learned from physics which has shaped your worldview, your ontology and your understanding of the world?

Heinrich Rohrer: I still cannot decide whether the world is what it is because of the natural laws or whether the natural laws are such in order that the world is the way it is.

Kourosh Ziabari: You have lived with the legacy of Nobel Prize for more than 2 decades and this is the most outstanding and appealing experience which a scientist may have after years of continued efforts and perseverance. What's your feeling about the Nobel Prize, its prominence and its role in your life? How much has your life changed since you won the Nobel Prize?

Heinrich Rohrer: The prominence of a prize rests on its recipients; they "make" the prize. Its external role I see that science stays every year for a couple of days in the limelight of attention by the public, at least in the countries with a newly chosen Nobel laureate. In certain respect nothing changed, I worked as hard as before. On the other hand, people thought twice before saying "no". Or this interview would not take place if I were not awarded a Nobel Prize. All in all, I think I did not loose the ground under my feet.

Kourosh Ziabari: We all know that the industrialized, developed world has invested a lot in sciences and in providing infrastructures and resources for academic studies, while the developing world, especially in the Middle East, is suffering from scientific deficiencies and we don't usually hear of remarkable scientific achievements and breakthroughs in this part of the world. What has made the U.S. and Europe different from the rest of the world? How have they climbed the zeniths of academic excellence and scientific success?

Heinrich Rohrer: I believe that history shows that any dominance, be it political, religious, technical, or intellectual, has a finite lifetime. All empires disappeared after hundreds to thousands of years or even shorter periods. The scientific-technical dominance moved from East ( China ) to the Near East , to the Mediterranean region and now is in middle and northern Europe and USA ; Australia and New Zealand are in this regard offspring of recent Europe . There are now clear signs of a rise again of the Far East region. Military powers take an end because more and more resources are used to keep in power; societies are threatened by decadence - whatever you mean with it. There probably are deeper reasons for rise and decline of societies but that is too delicate a subject to be discussed here. I consider the opening gap of scientific-technological capabilities between those who have and those who do not as the key threat for humankind.

Kourosh Ziabari: Please tell me more about your colleague Geld Binning and your experience with him. How was the experience of working with Geld? What's your evaluation of cooperation with him? You finally shared the Nobel Prize and your names always appear alongside each other in the press and scientific magazines.

Heinrich Rohrer: I hired Gerd Binning for working with me in a new field, inhomogeneity on a very small scale, which II saw becoming very important, in particular for the rapid progress of miniaturization of electronic components but which did not get adequate attention, not even in IBM. Gerd Binning is creativity in person. My down to earth thinking and good feeling for what is important and what not was an ideal complement to his bubbling ideas. And the chemistry between us was right, as one expresses it. Although I retired 13 years ago, Gerd is now back in Munich, and we both have left the STM activities long ago we have dinner together about once a month and undertake this and that together with our wives.

Kourosh Ziabari: Will you accept if you're asked to come to a developing or underdeveloped country to run and chair an academic institution dedicated to teaching basic sciences with the poor and needy students who are interested in physics, for example? How should the high-ranking scientists, like yourself, contribute to the improvement of science and technology in the developing world?

Heinrich Rohrer: No. I guess my time is over. I have terminated all my advisory mandates, preventively in order to keep reasonable healthy. The young scientist are the future, they need freedom, an open sky, and encouragement, not the protecting shade of a so called high-ranking scientist. I gave some thousand lectures in the Far East Europe and North America , some of them to interested citizens and many discussion rounds with young students from high school level up.

Kourosh Ziabari: What are your hobbies in the leisure time? Do you still spend your

free time studying physics and working on new projects?

Heinrich Rohrer: My hobbies were mountain hiking - not climbing - and gardening and some moderate sports such as soccer, tennis and golf. Since retirement, I do no longer take part in specific science projects, But I think about many angles of science, about the scientific values we are slowly sacrificing for an unscientific, business like pace. You can retire a scientist, but he can hardly retire his brain.

Kourosh Ziabari: For my final question, I would like to ask you to share with the young, science-loving readers of this interview, some words of wisdom; something like a life lesson, an except of what you have learned which has made you successful.

Heinrich Rohrer: Work hard to meet all the fabulous challenges in science and to overcome the abundant difficulties. But do not forget to enjoy life.

Kourosh Ziabari is an Iranian journalist

Comments are moderated