Pipeline Geopolitics: From South Stream To Blue Stream

By George Venturini

07March,2015

Countercurrents.org

On 1 December 2014, in Ankara, President Vladimir Putin announced that the South Stream gas pipeline would not be built. Mr. Alexei Miller, the head of Gazprom, Russia's state-run energy company, confirmed the news: “That's it. The project is over.”

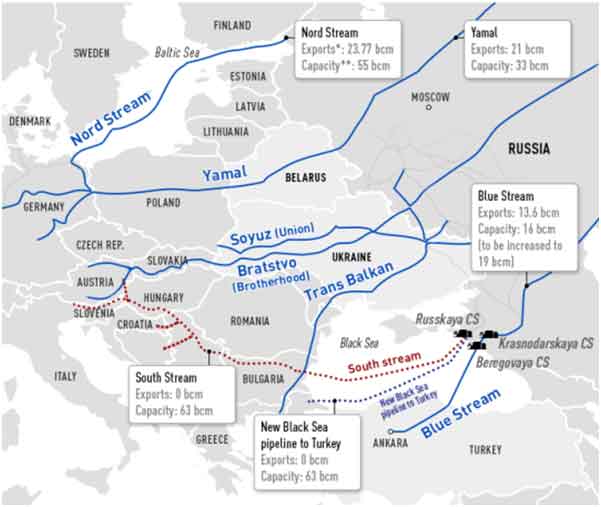

The 40 billion Euro pipeline was to have transported Russian gas from the Black Sea coast through Bulgaria, Serbia and Hungary to Austria, bypassing Ukraine en route. Another pipeline would have supplied Italy via Greece. The pipeline was to have had an annual capacity of 63 billion cubic metres, one-tenth of Europe's total gas demand. Gazprom had already invested 8 billion Euros (US$ 9.4 billion) in the project.

Putin blamed the European Union for the project's abandonment. “If Europe doesn't want this project, then it won't be realised.” he said. “Instead we will supply our energy sources to other regions in the world.”

According to the Bank of America Corporation, the United States is the world's biggest oil producer, after overtaking Saudi Arabia and Russia as extraction of energy from shale rock spurs the nation's economic recovery.

America's, production of crude oil, along with liquids separated from natural gas, surpassed all other countries in 2014 with daily output exceeding 11 million barrels in the first quarter, the bank said in a report 5 July 2014. The United States became the world's largest natural gas producer in 2010, and the International Energy Agency confirmed in June 2014 that the United States had become the biggest producer of oil and natural gas liquids.

It is evident that the United States is seeking both commercial advantage and political influence by gaining a foothold in Europe's oil and gas markets. Evidence comes, in part, from the targets the American administration has chosen to punish for Russia's annexation of the Crimean peninsula.

And the annexation of Crimea might just have been a way further to guarantee the completion of South Stream. All of this raises the question of how much the confrontation in the Ukraine is about who gain an advantageous position in the sale of natural gas, later of oil, to one of the world's biggest energy consumers: Europe.

Following the lengthy and costly disputes with Ukraine during 2005-2010, Russia began planning for the pipeline.

During the disputes, and when Russian gas flows through Ukraine were completely shut down on 7 January 2009, 18 countries ranging from large European Union members such as Germany to small ex Soviet Moldova were affected. In particular, Austria lost about 60 per cent of gas for domestic use, Bosnia about 100 per cent, Bulgaria about 96 per cent, Croatia about 37 per cent, the Czech Republic about 80 per cent, France about 24 per cent, Germany about 42 per cent, Greece about 82 per cent, Hungary about 60 per cent, Italy about 28 per cent, Macedonia about 100 per cent, Poland about 47 per cent, Romania about 28 per cent, Serbia about 87 per cent, Slovakia about 100 per cent, Slovenia about 64 per cent, Turkey about 67 per cent, while Moldova had adequate gas reserves only for 48 hours.

Gazprom proposed South Stream as a way to circumvent Ukraine and ensure an uninterrupted, diversified flow to Europe. It found a willing partner in E.N.I. - National Hydrocarbon Agency, the Italian state-controlled oil and gas company, and seven other gas-hungry countries.

To understand how important South Stream was to Russian economic influence over Europe, one only has to look at some of the targets of U.S. sanctions against Russian or Russian-linked companies. Two of them were directly aimed at slowing down or stopping South Stream.

On 11 April 2014 the United States Department of the Treasury ‘designated' seven individuals and a Crimea-based gas company as “contributing to the Situation in Ukraine and thus attracting sanctions.”

This was explained with reference to events of 18 March 2014. On that day, the Crimean parliament passed a resolution to seize the Crimean assets of a subsidiary of a Ukrainian state-owned gas company which has drilling rigs off Crimea's west coast and in the Sea of Azov. The assets were transferred to an entity with the same name, Chernomorneftegaz, literally ‘Black Sea oil and gas', an oil and gas company based in Simferopol, Crimea. The parliament's resolution said that the takeover would include ownership of the region's “continental shelf and the exclusive (maritime) economic zone.” Chernomorneftegaz had been ‘designated' pursuant to [Executive Order] 13660 “because it is complicit in the misappropriation of state assets of Ukraine or of an economically significant entity in Ukraine.”

As a result of Treasury's action, any assets of the persons ‘designated' and being within the United States jurisdiction were to be frozen, and transactions by American persons or with the United States involving these individuals and entities were generally prohibited.

This U.S. Treasury ‘designation' was followed by another on 28 April 2014, naming seven individuals and companies to be added to those listed by the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the Treasury.

Among the companies were: Aquanika, Avia Group LLC, Avia Group Nord LLC, Cjsc Zest, Investcapital Bank, JBS SobinBank, Sakhatrans LLC, SMP Bank, Stroygazmontazh, Stroytransgaz - all domiciled in Russia, Stroytransgasz Holding - domiciled in Cyprus, Stroytransgaz LLC, Stroytransgaz OJSC, The Limited Liability Company Investment Company Abros, Transoil and Volga Group - the latter domiciled in Luxembourg.

One most important of those companies was the group of Stroytransgaz, a subsidiary of which was building the Bulgarian section of the pipeline. The huge group is controlled by the Russian billionaire Gennady Timchenko, who happens to be a good friend of President Putin, and who had already been ‘designated' on 20 March 2014. Stroytransgaz was forced to stop construction of the pipeline or risk exposing other companies on the project to the sanctions.

Timchenko, who built his fortune as co-founder of the oil trading company Gunvor Group, said that he sold his stake in Gunvor the day before his name was placed on the first U.S. sanctions list on 20 March. Nevertheless, the new list, issued on 28 April, named Timchenko's Luxembourg-based Volga Group holding company, as well as ten businesses it controls, ranging from a mineral-water bottling company to industrial construction firms. Also targeted were three subsidiaries of Bank Rossiya, a previously sanctioned bank in which Volga Group holds an 8 per cent stake, according to the group's website. Another company controlled by Timchenko is Transoil, a Russia-based rail freight operator which specialises in the transportation of oil and oil products.

Another, and most important company ‘designated' on 11 April 2014 was Chernomorneftegaz. It was legally a subsidiary of Ukraine's state-owned oil and gas company Naftogaz. However, after the 2014 Crimean crisis it was seized by the region's parliament in the run-up to its annexation by Russia. As the name makes clear, the company owns the rights to the exclusive maritime economic zone in the Black Sea. The company is involved in the South Stream pipeline for the purpose of avoiding to pass through Ukraine and to go instead - quite south in the Black Sea - to Turkey.

The European Parliament reacted with the 16 April 2014 Resolution on Russian pressure on Eastern Partnership countries and in particular destabilisation of eastern Ukraine. Unfortunately, the resolution which called for a halt to the construction of South Stream pipeline was one non-binding. Member states of the European Union needed not feel bound by such a resolution. Clearly, its purpose was that of putting public pressure on Russia - no more.

Some countries complied, others did not. Several of them - those which were to benefit from the pipeline - spoke out in support of construction or moved ahead with agreements to build it.

Italy was determined to proceed. On 10 July 2014 the Italian E.U. presidency declared itself in favour of the pipeline: “We think South Stream should go ahead, as it would improve the diversification of gas routes to Europe.” said the Italian state secretary for E.U. affairs during a press conference in Brussels. He confirmed statements made by the Italian Foreign Minister while in visit to Moscow to meet with her Russian counterpart. The Italian minister said that the pipeline was “very important for the energy security of our country, as well as that of the entire European area”, but stressed that the project was to comply with E.U. law. On that occasion the Italian minister invited President Putin to a meeting of Asian and European leaders in Milan in October.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said during a press conference that Italy and Russia “confirm our goal on completing the construction project of the South Stream gas pipeline ... and to continue active work in order to remove all issues that may arise, including in regard to the dialogue with the European Commission.”

Work on the South Stream pipeline was halted in Bulgaria in June 2014 after the E.U. Commission said that it was in breach of the bloc's energy and public procurement laws. Bulgaria still has close ties to Russia but is subject to pressure from the United States. Both have taken aim at its section of South Stream, which is where the pipeline was to come ashore from Russia through the Black Sea. The European Union warned the Bulgarian government that its construction tender was in breach of E.U. rules. The United States sanctioned the company which had won the tender, Stroytransgaz.

Bulgaria cogently argued to the E.U. on 26 June 2014 that its position was legally sound, and that its economic stability was at risk without South Stream. Bulgaria has no other secure gas supply so “the national interest must be protected.” the Bulgarian Economy and Energy Minister said.

In the meantime, Bulgaria was hard at work to circumvent the U.S. sanctions. The government was considering handing the construction job to a subsidiary of Gazprom which was building the Serbian section. The Bulgarian government approved a US$ 835 million loan from Gazprom to pay for it, secured by future revenue from the pipeline.

The European Energy Commissioner said at the time that the ongoing Ukraine crisis had also made the E.U. wary of going ahead with the project.

The pipeline would have deprived Ukraine of transit revenues from the gas pipelines which cross its territory and bring about 80 per cent of Russian gas exports to E.U. countries. It would also have enabled it to cut off supplies to Ukraine to exert political pressure, without affecting its E.U. gas clients.

A former executive at Ukraine's gas distribution firm Naftogaz, told newspapers that, together with Nord Stream, Russia's recently-built pipeline to Germany, South Stream would give Moscow “a 100 percent monopoly on shipments of gas to Europe from the east.” He added also that it would make it less likely that the E.U. would ever build a gas pipeline to the Caspian Sea, the so-called Southern Corridor, to diversify supplies.

On 24 June 2014 Russia and Austria had agreed on a joint company to construct the Austrian arm of the US$ 45 billion South Stream project, which was expected to deliver 32 billion cubic meters of Russian gas to the country. The joint South Stream Austria project was to be 50 per cent owned by Gazprom and 50 per cent by Austria's OMV Group, the country's largest oil and gas company.

According to President Putin, South Stream was just a business venture facing ordinary commercial setbacks which had nothing to do with Ukraine. He claimed that the American administration was interfering, as Putin said after meeting with his Austrian counterpart on 24 June 2014.

The U.S. was opposed to the pipeline project because it wants to supply gas to Europe itself, President Putin said. “[The Americans] do everything to disrupt this contract. There is nothing unusual here. This is an ordinary competitive struggle. In the course of this competition, political tools are also being used.” said President Putin after holding talks with his Austrian counterpart, President Heinz Fischer, in Vienna.

“We are in talks with our contract partners, not with third parties. That our U.S. friends are unhappy about South Stream, well, they were unhappy in 1962 too, when the gas-for-pipes project with Germany was beginning. Now they are unhappy too; nothing has changed, except the fact that they want to supply to the European market themselves.” Putin stated. Should this happen, American gas “will not be cheaper than Russian gas - pipe gas is always cheaper than liquefied gas.” Putin had stressed.

President Putin took the occasion to emphasise that Moscow is not bypassing Ukraine for political reasons. “These are natural steps to expand the transport infrastructure.” Putin said. “[Russia is not] striving to bypass Ukraine.”

He reminded that the Nord Stream, South Stream, and Blue Stream projects started a while ago. “It is wrong always to say that we are doing anything against anyone.” Putin noted. He added that Russia, just like its “partners”, can and will “create the most favorable conditions, and have contacts and contracts with many partners.” Russia will continue “to promote our product in emerging market.” Putin stressed.

At the same time, Austrian President Fischer hailed the project, calling the South Stream gas pipeline “expedient” and “useful.” Fischer stated that if anyone criticised Austria, they should also criticise other member countries and their companies. “I suppose that there will be no such moment when such a country as Austria will not be holding talks with a partner, which has intense relations with us, and will not be ready to negotiate with it.” President Fischer said. “We know such a dialogue does not contradict any E.U. decision.” he added.

Construction of the Austrian section was expected to begin in 2015. The first deliveries could begin in 2017, reaching full capacity in January 2018.

Of course, the United States has a massive commercial interest in selling natural gas to Europe. Thanks to the abundant supply brought by the domestic shale-gas boom, the U.S. may be able to export liquefied natural gas to European buyers in the near future. Already, the American administration has licensed seven export facilities; about 30 more are awaiting approval.

The U.S. shale revolution has been driving a dramatic restructuring of global natural gas markets, not only arousing hopes for replicating the U.S. successes in similar shale formations outside the U.S., but also providing opportunities and incentives for moving “surplus” lower-cost U.S. gas into higher-value global markets through liquefied natural gas exports. Almost two dozen U.S. liquefied natural gas export projects have been proposed and as many as another dozen have been proposed in Canada. Seven U.S. projects, with a total of about 9 bcf/d of export capacity - equivalent to more than 12.5 per cent of current U.S. natural gas production - have received full export approvals. Approved export project capacity could have topped 10 bcf/d by the end of 2014. One of the approved projects was already under construction, with first exports expected by the end of the year.

Many of the proposed U.S. export projects will have significant cost advantages in that they are ‘brown-field' which will leverage existing liquefied natural gas import infrastructure and will have tackled some of the important regulatory and permitting challenges. Some proposed projects on the U.S. and Canadian West Coast will also enjoy distinct transportation advantages into the premium Asian markets. In short, costs-of-supply will matter.

Not all the infrastructure to ship liquefied gas was yet in place, and the Serbian Prime Minister Alexander Vucic, a South Stream proponent, had ridiculed the idea of U.S. gas exports to Europe in a year or two as “fairy tales.” Meanwhile, President Putin had pointedly said that piped gas will always be cheaper than the liquid form, and Russia has consistently claimed that Europe's gas bill will rise if it chooses alternatives besides its natural gas.

One should consider, in addition, that there is more than natural gas at play in Europe's energy future.

The American administration was actively negotiating a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership which could legalise American oil exports for the first time since 1975.

A document obtained by The Washington Post early in July 2014 revealed that the European Union was pressing the United States to lift its longstanding ban on crude oil exports through a sweeping trade and investment agreement. This is not entirely surprising. The E.U. has made its desire for the right to import U.S. oil known since the U.S. started producing large amounts of it in the mid-2000s. It signalled again at the outset of trade negotiations, and its intentions have become even clearer since.

This time, though, the E.U. was adding another argument: instability on its Eastern flank threatens to cut off the supply of oil and natural gas from Russia. “The current crisis in Ukraine confirms the delicate situation faced by the EU with regard to energy dependence.” read the document, which is dated 27 May 2014.

The disclosure came in advance of another round of discussions on the treaty, which began during the northern fall of 2013 and is expected to encompass US$ 4.7 trillion in trade between the U.S. and the European Union when it is finalised. That will not happen for several years - if ever, but knowledge of the E.U.'s position has inflamed the already-hot debate over whether to allow the U.S.' newfound bounty of crude oil to be exported overseas.

If the agreement were successful, American exporters would come into direct competition with Russia, which at per cent sells 84 percent of its oil and 76 percent of its natural gas exports to Europe.

If the standoff with Russia and ‘western' countries reaches a point where the European Union is forced to cut trade with Russia completely, oil prices could soar above US$ 200 per barrel, and gas prices would also rise steeply. Major economic downturns are associated with high energy prices.

Cutting off trade with Russia, the world's second largest oil exporter, would create a shortage in global energy supplies, which would have adverse consequences on to Europe. If Russian energy were banned from ‘western' markets Russia would lose 80 per cent of its energy exports. Producing countries of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries could fill in the market gap.

As of yet, Russia has not halted European gas supplied through politically unstable Ukraine, but this event itself could trigger ‘stage three', or trade-specific sanctions. The situation was dramatically complicated just after the middle of February 2015 when Gazprom had begun shipping gas directly to eastern Ukraine: on 19 February Gazprom C.E.O. Alexei Miller announced that his company was shipping 12 million cubic metres per day into Donetsk and Luhansk, the capitals of the rebel republics.

Exactly how this is going to work, financially, for Gazprom is unclear. Mr. Miller said that the shipments were made according to the existing purchase agreement with Ukraine's Naftogaz monopoly. In fact the shipments are going to rebel territory, outside of Naftogaz control, but Luhansk's rebel leader Gennady Tsypkalov claimed to have reached a separate agreement with Russia on allowing Gazprom to sell to them. Russian Premier Dmitry Medvedev had suggested meanwhile that his government was considering ‘humanitarian aid' to the eastern rebels in the form of natural gas shipments, which may ultimately be the basis for Gazprom's shipments.

In the meantime, western Ukraine is struggling through a fresh natural gas shortage, as their offensives against the east badly damaged the pipelines through which the gas is shipped from Russia, effectively cutting their territory off from Gazprom shipments.

Sanctions against Russia have been driven by the United States, followed by its vassal states like Australia, but Europe has been more reluctant to follow suit, since its economy is still fragile, and disruption with a close trading partner could further destabilise recovery. Russia is the E.U.'s third largest trading partner, and the largest economies, Germany, France and Italy have some of the strongest ties.

Had it gone ahead, the South Stream pipeline was projected to yield about US$ 20 billion a year in income. With that much money at stake, the politics behind the armed confrontation in eastern Ukraine takes on a new dimension. And the real question remains: is the shooting war there part of larger, longer-term conflict, a continuing confrontation between the United States and Russia for global energy dominance ?

* * *

The cancellation of South Stream is part of a broader change of strategy for Gazprom and it plays to the company's strengths.

The previous strategy was aimed at acquiring distribution networks deep in European markets. Such strategy was in part politically motivated. It was meant to exert Russian political power as much as to provide profits for Gazprom. That was one of the reasons which led the European Union to draw up regulations: obstruct it.

Building South Stream was to be expensive, conservatively priced at about US$ 20 billion and by some estimates as much as US$ 65 billion. It never made commercial sense, even when the European Union demand for gas was projected to soar and Gazprom was planning to control prices by negotiating separate long-term contracts with individual buyers.

Today Gazprom faces new price competition from spot markets at gas hubs around the European Union. Furthermore, new E.U. rules - some of them still being written - were intended to force Gazprom to open up its European pipelines to other suppliers and distributors.

The Ukraine crisis prompted E.U. officials to move aggressively against South Stream for not complying with the rules already laid down. And collapsing oil prices - to which long-term gas contracts are tied - made the economics of South Stream look even worse. Eventually, Gazprom abandoned the project.

Instead, the company proposed redirecting the pipeline project to Turkey, its second-largest customer in Europe and the only European market projected to grow strongly. The gas Turkey now receives through Ukraine would come directly from Russia; any additional amounts could be taken to a hub at Turkey's E.U. border and sold. Nevertheless, Gazprom would still need to send substantial amounts of gas to Europe through Ukraine until at the very least 2020.

Perhaps there were other reasons for Gazprom abandoning the project. Not long before the announcement Gazprom had finally agreed on terms to supply huge quantities of piped gas to China.

The agreement between President Putin and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will strengthen economic ties between the two nations and make Turkey the major hub for Russian gas in the region. Under the terms of the agreement, Russia will pump additional natural gas to locations in central Turkey and to a ‘hub at the Turkish-Greek border' which will eventually provide Putin with backdoor access to the lucrative E.U. market, although Turkey will serve as the critical intermediary.

The agreement signifies a de facto Russo-Turkish alliance which could shift the regional balance of power decisively in Moscow's favour, thus creating another formidable hurtle for the American administration ‘pivot to Asia' strategy. While the media are characterising the change in direction of the South Stream as a ‘diplomatic defeat' for Russia, the opposite appears to be the case. Putin has once again outmanoeuvred the United States on both the energy and geopolitical fronts adding to his long list of policy triumphs.

Not many commentators seem to grasp the magnitude of what happened in Ankara, although - judging by the American administration's silence on the topic - the importance of the transaction is beginning to sink in.

In Ankara Putin said that Russia is ready to build a new pipeline to meet Turkey's growing gas demand, which may include a special hub on the Turkish-Greek border for customers in southern Europe.

“For now, the supply of Russian gas to Turkey will be raised by 3 billion cubic meters via the already operating Blue Stream pipeline.” Putin said. Moscow would also have reduced the gas price for Turkish customers by 6 per cent from 1 January 2015. Putin said. “We are ready to further reduce gas prices along with the implementation of our joint large-scale projects.” he added.

The American administration has been doing everything in its power to control the flow of gas from east to west and to undermine Russian-European Union economic integration. Now it looks like President Putin has found a way to avoid the effects of economic sanctions. Turkey had rejected sanctions on Russia, was assiduously avoiding United States coercion and undue pressures - which were applied to Bulgaria, Hungary and Serbia, as well as avoiding the United States endless belligerence and hostility, while achieving its objectives at the same time.

The American administration was completely surprised by the announcement and cannot quite realise what the agreement means for the issues which are on the very top of its foreign policy agenda: the ‘pivot to Asia', the wars in Syria and Ukraine, or the much-cultivated gas pipeline from Qatar to the European Union, which was supposed to transit through Turkey.

A 3 December 2014 article in The New York Times precisely examined the American administration's ambivalence towards the South Stream project. Here is the gist: “Moscow has long presented the project, proposed in 2007, as making good business sense because it would provide a new route for Russian gas to reach Europe. Washington and Brussels have opposed the project on the grounds that it was a vehicle for cementing Russian influence over southern Europe and for bypassing Ukraine, whose price disputes with Gazprom twice interrupted supplies to Europe in recent years.”

That appeared to be propaganda paid for by the people in the oil industry who lost the competition for supplying fuel to the E.U. Their much advertised pipeline, Nabucco, had failed.

In addition, the countries that South Stream would have served, do not have an alternative supplier to meet their growing gas needs. Analysts calculate that any replacement for Russian gas will probably be 30 per cent more expensive than they would have paid Gazprom.

The United States has been determined to sabotage South Stream from the very beginning, mainly because it favours its corporations and banks to control the flow of gas to the European Union market through privately-owned pipelines in Ukraine. In that way they can make bigger profits for their shareholders.

And there is more: two months before the Ukraine government was overthrown the prime minister of Bulgaria, Plamen Oresharski, ordered a halt to work on the South Stream on the recommendation of the E.U. The decision was announced after his encounter with three ‘neo-liberal' United States senators: Ron Johnson, John McCain, and Chris Murphy. “At this time there is a request from the European Commission, after which we've suspended the current works, I ordered it.” Oresharski told journalists. “Further proceedings will be decided after additional consultations with Brussels.”Brussels, of course, feared that the pipeline would cement Gazprom's domination of the European gas market.

On the other hand, South-eastern Europeans were looking forward to earning money from transit fees.

Representatives of Bulgaria, Hungary and Serbia said that they had received no advance warning that Russia was abandoning South Stream, even though they all have substantial financial and political capital invested. Russia said it would export its gas to a trade hub in Turkey instead.

At a meeting in Brussels of E.U. ambassadors on 2 December 2014 the Hungarian representative asked Ms. Federica Mogherini, the new E.U. foreign policy head: “First Nabucco, now South Stream. What are we supposed to do now?” Peter Szijjarto, Hungary's foreign minister, said that alternative sources of energy would now have to be explored, including gas from Azerbaijan.

Aleksandar Vucic, Serbia's prime minister, told his country's R.T.S. channel that the decision was bad news for Belgrade and said he would urgently seek to speak with President Putin. “Serbia has been investing in this project for seven years, but now it has to pay the price of a clash between the great [powers].” he said.

Italy and Austria had also been vocal supporters of the venture, pitting themselves against the European Commission.

Businesses involved in South Stream include Italy's E.N.I. and Austria's O.M.V. Saipem and Salzgitter, too, lamented that they had received no notification from Russia that their contracts were being terminated.

Stocks in Italian oil services group Saipem closed down 10.8 per cent, while Germany's Salzgitter, the joint venture of which was making pipes for the project, was down 7.4 per cent. In January 2014 Europipe - Salzgitter's joint venture, had won half of a 1 billion Euro tender for the first pipeline to supply specialised pipes capable of withstanding depths of 2,200 metres. The other winning contractors were Russia's United Metallurgical Company - O.M.K. and Severstal. Voestalpine supplied steel plates to O.M.K. Salzgitter was relying on the project to take up capacity at the Europipe mill in Muelheim until 2015. Low orders previously forced the company to cut the hours of some of its workers.

The dispute over South Stream also sowed such divisions in the E.U. that it proved difficult to agree on sanctions against Moscow, diplomats said.

The 28-member bloc insisted that its opposition to South Stream was legal, not political.

* * *

The reality was somewhat different: Russia had been forced to withdraw from the South Stream project because of the European Union's unwillingness to support the pipeline. And so it decided that gas flows would be redirected to other customers, President Putin had clearly said after talks with his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

“We believe that the stance of the European Commission was counterproductive. In fact, the European Commission not only provided no help in implementation [of the pipeline], but, as we see, obstacles were created to its implementation. Well, if Europe doesn't want it implemented, it won't be implemented.” the Russian President said.

According to Putin, the Russian gas “will be retargeted to other regions of the world, which will be achieved, among other things, through the promotion and accelerated implementation of projects involving liquefied natural gas.”

“We'll be promoting other markets and Europe won't receive those volumes, at least not from Russia. We believe that it doesn't meet the economic interests of Europe and it harms our cooperation. But such is the choice of our European friends.” he said.

The South Stream project was at the stage when “the construction of the pipeline system in the Black Sea should have begun.” but Russia still had not received an approval for the project from Bulgaria, the Russian President said.

Investing hundreds of millions of dollars into the pipeline, which would have had to stop when it reached Bulgarian waters, was “just absurd, [and] I hope everybody understands that.” he said.

Putin clearly stated that Bulgaria “isn't acting like an independent state” by delaying the project, which would have advantageous to the country.

He advised the Bulgarian leadership “to demand loss of profit damages from the European Commission” as the country could have been receiving around 400 million Euros annually through gas transit.

The crisis in Ukraine had turned the legal debate over the pipeline into a political issue, affecting the E.U.'s willingness to find a solution to the deadlock. As a result, the European Commission had been pressuring member states to withdraw from the project, with the new Bulgarian government saying it would not allow Gazprom to lay the pipeline without permission from Brussels.

The decision makes no economic sense, Mr. Maroš Šefcovic, the European Commission's vice president for energy, was to tell reporters on 15 December 2014 after talks with Russian government officials and the head of Gazprom, in Moscow. During the discussion Mr. Miller had confirmed that Gazprom was planning to send 63 billion cubic meters through the proposed link under the Black Sea to Turkey, fully replacing shipments via Ukraine.

Mr. Šefcovic sounded “very surprised” by Mr. Miller's comment, adding that relying on a Turkish route, without Ukraine, would not fit with the E.U.'s gas system. He could not understand how Gazprom would plan to deliver the fuel to Turkey's border with Greece and “it's up to the E.U. to decide what to do” with it further.

On 15 January 2015 Russia had cut gas exports to Europe by 60 per cent, plunging the continent into an energy crisis ‘within hours' as the dispute with Ukraine on price and past debts escalated. Six countries - Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Macedonia, Romania and Turkey - had reported a complete shut-off of Russian gas shipped via Ukraine, in a sharp escalation of a struggle over energy which threatens Europe as winter set in.

“We have informed our European partners, and now it is up to them to put in place the necessary infrastructure starting from the Turkish-Greek border.” Mr. Miller said.

Russia would not hurt its image with a shift to Turkey because it has always been a reliable gas supplier and never violated its obligations, Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak told reporters in Moscow after meeting Mr. Šefcovic.

“The decision has been made.” Novak said. “We are diversifying and eliminating the risks of unreliable countries which caused problems in past years, including for European consumers.”

* * *

Almost simultaneously with President Putin's announcement, and with a view to assuage the fear that countries in Europe might end up shivering in the forthcoming winter as they had in 2009, when a spat over Ukraine's gas bill prompted Russia to cut off energy supplies to Europe for nearly two weeks, Mr. Miller announced that Russia would have resumed shipping natural gas to Ukraine after Kiev paid off its first debt installment for past supplies of gas. Mr. Miller made the statement hours after Russia, Ukraine and the European Union had thrashed out a US$ 4.6 billion deal that will guarantee Russian gas supplies to Ukraine and further on to the E.U.

In June 2014 Russia had cut off gas supplies to Ukraine over unpaid debts, a move which followed the ouster of Ukraine's Russia-friendly leader and the Kremlin's annexation of Crimea in March. Talks dragged on for five months amid fighting in eastern Ukraine between pro-Russian insurgents and government troops. But the looming onset of northern winter - a fierce, freezing season in Ukraine - had given the talks increasing urgency.

In return for the resumption of supply, Gazprom expected to receive the first Ukrainian tranche of US$ 1.45 billion before the end of the following week and promised to re-start gas supplies to Ukraine within 48 hours after receiving the payment. Under the new agreement, Ukraine has pledged to pay the rest of its US$ 3.1 billion gas debt before the end of 2014 and also to pay in advance for Russian gas supplies through March.

Russia claimed that Ukraine owed it US$ 5.3 billion for past supplies, while Ukraine only acknowledges a debt of US$ 3.1 billion. The difference was based on a discounted price Moscow offered to Ukraine under the previous president but annulled after his ouster.

An E.U.-brokered compromise meant that gas supplies would resume on condition that Ukraine pays the amount of debt it accepts - the debt to be determined through arbitration.

The E.U. said that it had been working closely with international institutions to help foot the gas bill, since Ukraine's economy was in dire straits.

European Union spokeswoman Ms. Marlene Holzner said that the E.U. decided to disburse 760 million Euros (US$ 954 million) of macro-financial aid for Ukraine earlier than scheduled to help it purchase gas. She made it clear, however, that the E.U. had given no pledge to step in and pay if the Kiev government could not or would not do so.

How had Ukraine reach such precarious condition ? The country is well-known for its riches.

According to recent information, it could be safely said that Ukraine has 395 million barrels of proven oil reserves, although the majority of them are located in the eastern Dnieper-Donetsk basin, which is the hands of the separatists. Ukraine has made efforts at exploration, particularly in its sector of the Sea of Azov, but oil production has remained relatively flat since independence. According to the 2008 British Petroleum Statistical Energy Survey, Ukraine consumed an average of 324.67 thousand barrels a day of oil in 2007.

Ukraine's geographic location makes it an important corridor for oil and natural gas to transit from Russia and the Caspian Sea region to Europe. During 2006 Ukraine pipelines had carried 22 per cent of Russia's exports to Ukraine refineries and Europe. Ukraine has six crude oil refineries, with a combined throughput capacity of approximately 880,000 bbl/d - the unit of volume for crude oil and petroleum products, per day.

From the same B.P. Statistical Energy Survey for 2008, one can gather that Ukraine had 2007 proved natural gas reserves of 1.02 trillion cubic metres, 0.57 per cent of the world total. According to the same survey, Ukraine had 2007 natural gas production of 19 billion cubic metres and consumption of 64.64 billion cubic metres. Ukraine is the sixth largest consumer of gas in the world.

As is the case with oil, Ukraine plays a significant role as an intermediary connecting Russia, the world's largest natural gas producer, with growing European markets. Ukraine's aging natural gas infrastructure is of concern both to European consumers and Russian producers.

Oil and gas have for a long time subjects to disputes between Russia and Ukraine. Such disputes have occurred mainly between the Naftohaz Ukrayiny company and the Gazprom. They concerned problems with natural gas supplies, prices and debts. These disputes have grown beyond simple business disputes into transnational political issues - involving political leaders from several countries - which threaten natural gas supplies in numerous European countries dependent on natural gas imports from Russian suppliers, which are transported through Ukraine. Russia provides approximately a quarter of the natural gas consumed in the European Union; approximately 80 per cent of those exports travel through pipelines across Ukrainian soil prior to arriving in the E.U.

A serious dispute began in March 2005 over the price of natural gas supplied and the cost of transit. During this conflict, Russia claimed that Ukraine was not paying for gas, but diverting that which was intended to be exported to the E.U. from the pipelines. Ukrainian officials at first denied the accusation, but later Naftohaz admitted that natural gas intended for other European countries was retained and used for domestic needs. The dispute reached a crescendo on 1 January 2006, when Russia cut off all gas supplies passing through Ukrainian territory. On 4 January 2006 a preliminary agreement between Russia and Ukraine was achieved, and the supply was restored. The situation calmed until October 2007 when new disputes began over Ukrainian gas debts. This led to reduction of gas supplies in March 2008. During the last months of 2008 relations once again became tense when Ukraine and Russia could not agree on the debts owed by Ukraine.

In January 2009 this disagreement resulted in supply disruptions in many European nations, with eighteen European countries reporting major drops in or complete cut-offs of their gas supplies transported through Ukraine from Russia. In September 2009 officials from both countries stated that they felt the situation was under control and that there would be no more conflicts on the subject, at least until the Ukrainian 2010 presidential elections. However, in October 2009, another disagreement arose about the amount of gas that Ukraine would import from Russia in 2010. Ukraine intended to import less gas in 2010 as a result of reduced industry needs because of its economic recession; however, Gazprom insisted that Ukraine fulfil its contractual obligations and purchase the previously agreed upon quantities of gas.

On 8 June 2010 a Stockholm court of arbitration ruled that Naftohaz must return 12.1 billion cubic metres - 430 billion cubic feet of gas to RosUkrEnergo, a Swiss-based company in which Gazprom controls a 50 per cent stake. Russia accused Ukrainian side of siphoning gas from pipelines passing through Ukraine in 2009. Several high-ranking Ukrainian officials stated that the return “would not be quick.”

Several views have been put forward as to alleged political motives behind the gas disputes, including Russia exerting pressure on Ukrainian politicians or attempting to subvert E.U. and N.A.T.O. expansions to include Ukraine. Others suggested that Ukraine's actions were being orchestrated by the United States. Both sides tried to win sympathy for their arguments fighting a public relations war.

After meeting her Russian counterpart [then] Prime Minister Putin, Ukrainian Prime Minister Tymoshenko declared on 3 September 2009: “Both sides, Russia and Ukraine, have agreed that at Christmas, there won't be [any halt in gas supplies], as usually happens when there are crises in the gas sector. Everything will be quite calm on the basis of the current agreements.” Tymoshenko also said that the Ukrainian and Russian premiers had agreed that sanctions would not be imposed on Ukraine for the country buying less gas than expected and that the price of Russian gas transit across Ukraine may grow 65 per cent till 70 per cent in 2010. A week before Gazprom had said that it expected gas transit fees via Ukraine to rise by up to 59 per cent in 2010.

The new Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov and Energy Minister Yuriy Boyko were in Moscow late March 2010 to negotiate lower gas prices; neither clearly explained what Ukraine was prepared to offer in return. Following these talks Russian Prime Minister Putin stated that Russia was prepared to discuss the revision of the price for natural gas it sells to Ukraine.

On 21 April 2010 [then] Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and [then] Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych signed an agreement in which Russia agreed to a 30 per cent drop in the price of natural gas sold to Ukraine. Russia agreed to this in exchange for permission to extend Russia's lease of a major naval base in the Ukrainian Black Sea port of Sevastopol for an additional 25 years with an additional five-year renewal option - to 2042-47. As of June 2010 Ukraine pays Gazprom around $234/mcm - thousand cubic metres. This agreement was subject to approval by both the Russian and Ukrainian parliaments. They did ratify the agreement on 27 April 2010. Opposition members in Ukraine and Russia expressed doubts that the agreement would be fulfilled by the Ukrainian side. Yanukovych defended the agreement as a tool to help stabilise the state budget. Opposition members in Ukraine described the agreement as a sell out of national interests.

In February 2014 Ukraine's state-owned oil and gas company Naftogaz sued Chornomornaftogaz for delayed debt payments of 11.614 billion hryvnia - UAH, almost 1 billion Euros in the Economic Court of the Crimean Autonomous Republic.

In March 2014 Crimean authorities announced that they would nationalise the company. Crimean deputy prime minister Rustam Temirgaliev said that Russia's Gazprom would be its new owner. A group of Gazprom representatives, including its head of business development, has been working at the Chornomornaftogaz head office since mid-March 2014. Chornomornaftogaz was a subsidiary of Ukraine's state-owned oil and gas company Naftogaz. However, after the 2014 Crimean crisis it was seized by the region's parliament in the run-up to its annexation by Russia. On 1 April Russia's energy minister Alexander Novak said that Gazprom would finance an undersea gas pipeline to Crimea.

On 11 April 2014 the U.S. Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control announced that it had added Chornomornaftagaz to the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List as part of the third round of U.S. sanctions. Reuters quoted an anonymous U.S. official who explained that the United States wanted to make it impossible for Gazprom “to have dealings with Chornomorneftegaz”, and if that were to happen, Gazprom itself could face sanctions.

The European Union followed suit on 13 May 2014, the first time its sanctions list included a company - in addition to Chornomorneftegaz, a Crimean oil supplier called Feodosia was also included.

In an attempt at energy independence, Naftogaz signed a pipeline access deal with Slovakia's Eustream on 28 April 2014. Eustream and its Ukrainian counterpart Ukrtransgaz, controlled by Naftogaz, agreed to allow Ukraine to use a never used - but aging, at 20 years old - pipeline on Slovakia's eastern border with Uzhhorod in western Ukraine. The deal would provide Ukraine with 3 billion cubic meters of natural gas beginning in autumn of 2014 with the aim of increasing that amount to 10 billion cubic meters in 2015.

On 1 April 2014 Gazprom cancelled Ukraine's natural gas discount as agreed in the 17 December 2013 Ukrainian-Russian action plan because its debt to the company had risen to US$ 1.7 billion since 2013. Later that month the price ‘automatically' jumped to US$ 485 per 1,000 cubic meters because the Russian government annulled an export-duty exemption for Gazprom in place since the 2010 Kharkiv Pact - the agreement having been repudiated by Russia on 31 March 2014. On 16 June 2014 Gazprom stated that Ukraine's debt to the company was US$ 4.5 billion.

After intermediary trilateral talks, started in May 2014, among the E.U. Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger, Ukraine and Russia failed on 15 June 2014 the latter halted its natural gas supplies to Ukraine the next day. Unilaterally Gazprom decided that Ukraine had to pay upfront for its natural gas. The company assured that its supplies to other European countries would continue. Ukraine vowed to “provide reliable supply of gas to consumers in Ukraine and we will provide reliable transit to the European Union.” At the time about 15 per cent of European Union's demand depended on Russian natural gas piped through Ukraine.

Early in March 2014 analysts had competed on announcing that, far from being impotent in the Ukraine crisis, the United States had a very important weapon: growing oil and natural gas production which could compete on the world market and challenge Russian dominance over Ukrainian and European energy supplies - if only the U.S. government would change the laws and allow this bounty to be exported.

But, there still is one very big problem with this view. The United States is still a net importer of both oil and natural gas. The economics of natural gas exports beyond Mexico and Canada - which are both integrated into a North American pipeline system - suggest that such exports will be very limited if they ever come at all. And there is no reasonable prospect that the United States will ever become a net exporter of oil.

United States net imports of crude oil and petroleum products are approximately 6.4 million barrels per day - mbp/d. This estimate sits between the official U.S. Energy Information Administration numbers of 5.5 mbp/d of net petroleum liquids imports and 7.5 mbp/d of net crude oil imports. These data refer to December 2013.

The E.I.A. in its own forecast predicts that U.S. crude oil production - defined as crude including lease condensate - will experience a tertiary peak in 2016 around 9.5 mbp/d just below the all-time 1970 peak and then decline starting in 2020. This level is far below 2013 U.S. consumption of about 13.2 mbp/d of actual petroleum-derived liquid fuels.

So, one could ask: when exactly is the United States going to drown the world market in oil and thereby challenge the Russian oil export machine ? The most plausible answer is never. And, the expected 2016 peak in U.S. production is only about 1.5 mbp/d higher than the present production. That is really quite small compared to worldwide oil production of about 76 mbp/d. And there is no guarantee that the rest of the world is not going to see a decline in oil production between now and then. So much for the supposed U.S. oil ‘weapon' taming the Russian bear.

But what about natural gas ? It is thought that America's great bounty of natural gas from shale could challenge the Russians. But it is not so. It is true that U.S. natural gas production increased significantly from its post-Katrina nadir in 2005. But such up-trend has now stalled. U.S. dry natural gas production has been almost flat since January 2012. The E.I.A. reports total production of 24.06 trillion cubic feet - tcf for 2012 and 24.28 tcf for 2013, a rise of only 0.9 per cent year over year.

And, here is a an unexpected difficulty: in order to ship U.S. natural gas to Europe or Asia, it must be liquefied at -260 degrees F - approximately equal to 126.7 degrees Celsius, shipped on special tankers and then regasified. The cost of doing this is about US$ 6 per thousand cubic feet - mcf. So, the total cost of delivering US$ 6 U.S. natural gas to Europe is around US$ 12 per mcf. With European liquefied natural gas prices mostly below this level for the last five years, it is hard to see Europe as a logical market. Japan would be a better target for such exports with prices moving between US$ 15 and US$ 18 per mcf in the last five years. But a U.S. entry into the liquefied natural gas market could conceivably depress world prices and make even Japan a doubtful destination for U.S. liquefied natural gas. An additional problem would be presented by a significant price rise above US$ 6. And, what if U.S. prices rise significantly above US$ 6 ? Of course, all these calculations presuppose that the United States will have excess natural gas to export.

The much talked about United States supplies of expensive shale gas to Europe have not materialised due to high costs. There is no alternative to Russian gas in Europe, at least in the near future.

Does the agreement reached in Ankara make the South Stream dead ? True, the project in its previous form is a thing of the past. Russia may return to it but only on its own terms, and only in an unforeseeable future. The time is right to concentrate on the new project. Many experts believe that the route should be continued from the point at the Greek border. The European Union has done its best to hinder the South Stream so now it will have to shoulder the financial burden. If the E.U. wants to optimise the expenditure according to the wishes of interested member-states, then it will have to make gas flows follow the previously planned route across Greece and Macedonia to Serbia, Hungary and Austria. Some efforts have already been applied to start the construction. It may make the route longer but will not require additional expenditure unavoidable in case of sea bed pipeline construction.

The only country to be left out will be Bulgaria as it failed to make an independent decision and could not resist the pressure to reject the South Stream.

* * *

In these circumstances what is the use of sanctions other than a political one ?

As for Russia, there is more than one reason whereby it is interested in Crimea and the Ukraine just as there is more than one reason why the United States is so interested in the imposition of economic sanctions. One of the reasons is likely related to the potential for oil and natural gas reserves on and adjacent to the Crimean Peninsula and onshore in both eastern and western Ukraine, a topic which has received little attention from the world's media until the geopolitical situation in Ukraine started to heat up.

At the time of the U.S.S.R. the oil industry discovered indications of hydrocarbons, but productivity was poor. Flow rates were low and were considered sub-economic, given that the porosity in the fractured reservoirs was low. With recent advances in production techniques, the potential to produce hydrocarbons from these tights reservoirs has increased substantially, particularly with the use of ‘fracking' to produce natural gas and condensate from shale reservoirs. ‘Fracking' has resulted in many oil and gas wells attaining a state of economic viability, due to the level of extraction which can be reached.

These are two key areas for potential accumulations in Ukraine, offshore in the Black Sea around Crimea and onshore in both eastern and western Ukraine.

Ukraine State Service of Geology and Mineral Resources announced that shale gas reserves in the country totalled 246 tcf. If this were the case, Ukraine alone would have just over half of the total gas reserves among all European nations which were not formally part of the Soviet bloc.

According to the United States Energy Information Administration, Ukraine has Europe's third largest unproved, technically recoverable shale gas reserves after Poland and France.

It is well known that, just before the ousting of the Yanukovych government, Ukraine was very close to signing a US$ 735 million production-sharing with Exxon/Mobil and Royal Dutch Shell. The deal would have seen two wells drilled off the southwest coast of Crimea in the Skifska area.

Exxon/Mobil announced in early March 2014 that further activity on its Skifska licence was on hold until the political situation in Ukraine was resolved.

Shale gas in Ukraine is located in two main areas, Yusivska located in eastern Ukraine and Olesska located in western Ukraine. According to E.I.A.'s 2013 shale gas report, Ukraine has 128 tcf of natural gas and 0.2 billion barrels of oil in its shale gas fields located in the black shale of Dnieper-Donets Basin in eastern Ukraine, the basin which accounts for most of Ukraine's onshore petroleum reserves and the organic riche shales of the Carpathian Foreland Basin in western Ukraine.

In May 2012 Ukraine chose Chevron Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell to explore and develop two potential onshore shale gas fields in western and eastern Ukraine.

In western Ukraine Chevron was initially to invest US$ 350 million annually, with a total investment of around US$ 10 billion. A 50 year production-sharing agreement was signed in November 2013, just a few months before mass protests in Kiev concluded with the ousting from office of President Yanukovich, plunging the country into a major crisis with Russia. Local media indicated that a move by the first post-Yanukovich government to increase taxes for energy companies lay at the root of the Chevron's decision. The Olesska shale reserves, located in western Ukraine, are estimated to be about 53 tcf according to the Ukraine government and could produce up to 350 bcf - billion cubic feet annually.

The deal to develop the Olesska field followed a similar shale gas agreement with Royal Dutch Shell - both keystone projects for Ukraine's bid to lessen its energy dependence on Russia with which it was embroiled in a dispute over gas prices and unpaid debts. The Shell deal could also be under threat as the gas deposit intended for development is close to the eastern territories now controlled by pro-Russian separatists.

At mid-January 2014 Chevron had announced that it would start producing gas by the end of 2014. But at mid-December 2014 Chevron was planning to withdraw from the $ 10 billion shale gas deal with the Kiev government, according to the announcement of a senor Ukrainian presidential official.

Ukraine also signed a contract with Royal Dutch Shell to explore shale gas potential on the Yuzivska block in eastern Ukraine. This area is estimated to have between 71 and 107 Tcf of shale gas and hell has made an initial spending of commitment of US$ 200 million in the first stage of exploration and an anticipated minimum of US$ 10 billion - possibly up to US$ 50 billion over the 50 year life of the agreement. Shell was expected to start production from the Yuzivska block in 2015.

Interestingly, in June 2013 Ukraine's Prime Minister Mykola Azarov claimed that Ukraine would be natural gas self-sufficient within ten years and that it would be able to export some gas as well by the mid-2020s. With Ukraine currently receiving over two-thirds of its natural gas from Russia and being Russia's second largest natural gas customer, one could wonder how much of a role recent oil industry activity in Ukraine and Crimea, in particular, have played in Russia's current political moves in the area. With major international oil corporations about to break Russia's near monopoly on natural gas in Ukraine, one could reasonably suspect that Russia and Gazprom would feel somewhat threatened. Looking at how many deals Ukraine has signed with multinational oil corporations, particularly American corporations, in the past two years, the timing of Russia's return to the Ukraine and American intervention in the situation seems more than coincidental.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration Independent Statistics and Analysis periodically produces ‘country analysis notes'. What follows is from a March 2014 analysis note about Ukraine.

Ukraine's geographic position and proximity to Russia explain its importance as a natural gas and petroleum liquids transit country. Approximately 3.0 trillion cubic feet of natural gas flowed through Ukraine in 2013 to Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Turkey.

Two major pipeline systems carry Russian gas through Ukraine to Western Europe - the Bratstvo (Brotherhood) and Soyuz (Union) pipelines. The Bratstvo pipeline is Russia's largest pipeline to Europe. It crosses from Ukraine to Slovakia and splits into two directions to supply northern and southern European countries. The Soyuz pipeline links Russian pipelines to natural gas networks in Central Asia and supplies additional volumes to central and northern Europe. A third major pipeline through Ukraine delivers Russian natural gas to the Balkan countries and Turkey. In the past, disputes between Russia and Ukraine over natural gas supplies, prices, and debts have resulted in interruptions to Russia's natural gas exports through Ukraine, with the latest one occurring in 2009.

The 400,000 bbl/d southern leg of the Druzhba oil pipeline transports Russian crude oil through Ukraine to supply most of the oil consumed by Bosnia, Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia. In 2013, about 300,000 bbl/d of throughput transited the pipeline. Russian crude oil and petroleum products also transit Ukraine by rail for export out of Ukrainian ports.

More than half of the country's primary energy supply comes from its uranium and coal resources, although natural gas also plays an important role in its energy mix. Ukraine consumed approximately 1.8 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in 2012, with domestic production accounting for approximately 37 per cent of the total at 694 billion bcf. The remainder of supply is made up by Russian natural gas, imported through the Bratstvo and Soyuz pipelines.

In 2012 Ukraine generated a total of 185 billion kilowatt hours of electricity. The country is heavily dependent on nuclear energy - its fifteen reactors generate roughly half of the total electric power supply. Fossil fuel sources - 46 per cent and hydropower - 6 per cent generate the remainder of Ukraine's electric power, with marginal volumes contributed by wind generation.

Most of Ukraine's primary energy consumption is fuelled by natural gas - about 40 per cent, coal - about 28 per cent, and nuclear - about 18 per cent. Only a relatively small portion of the country's total energy consumption is accounted for by petroleum and other liquid fuels and renewable energy sources.

In 2012 Ukraine consumed 319,000 barrels per day of liquid fuels, but produced only 80,400 bbl/d. The remainder was imported mostly from Russia, with smaller volumes originating in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. A payment issue caused Russia to halt crude oil deliveries to Ukraine's 56,000 bbl/d Odessa refinery in January 2014.

Recent discoveries of shale gas deposits in Ukraine provide the country with a possible means to diversify its natural gas supplies away from Russia. In January 2013 Shell agreed to explore an area which the government estimates holds about 4 tcf of shale natural gas in reserves. Current plans include development of shale gas resources for domestic consumption and exports to western Europe by 2020.

Burisma Holdings Limited is a privately controlled oil and gas company with assets in Ukraine and operating in the energy market since 2002. To date the company holds a portfolio with permits to develop fields in the Dnieper-Donets, the Carpathian and the Azov-Kuban basins. In 2013 the daily gas production grew steadily and at year-end amounted to 11.6 thousand boe - barrels of oil equivalent - including gas, condensate and crude oil, or 1.8 million cubic metres of natural gas. The company sells these volumes in the domestic market through traders, as well as directly to final consumers.

Burisma Holdings engages in oil and gas exploration and production. The company also engages in oil well drilling, production of liquefied natural gas, and undertaking geological studies. The company was incorporated in 2006 and is based in Limassol, Cyprus.

During 2009-2013 the flow rate of the Group rapidly grew. According to Burisma, by the end of 2013 it reached a daily production of about 11,600 barrels of oil equivalent. This is equivalent to about nine per cent of the current gas flow in the Ukraine.

In 2013 Burisma launched a major management restructuring, which should initiate a ‘new period of growth' in the company's history. In the course of this restructuring the American investment banker Alan Apter was hired as Chairman of the Board of Directors with the task to improve the corporate governance of the company and to attract foreign capital. Apter has extensive professional experience from activities in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

On 12 May 2014 Burisma reported that an additional seat was set up in the Board of Directors for R. Hunter Biden, the U.S. Vice President's son. This caused an international media echo connection with the crisis in the Ukraine of 2014. Attention focused also on the Polish ex-President Aleksander Kwasniewski and on Devon Archer, former campaign manager of U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry.

Mr. Biden will be in charge of Burisma's legal unit and to provide support for the company among international organisations. On his new appointment, he commented: “Burisma's track record of innovations and industry leadership in the field of natural gas means that it can be a strong driver of a strong economy in Ukraine. As a new member of the Board, I believe that my assistance in consulting the Company on matters of transparency, corporate governance and responsibility, international expansion and other priorities will contribute to the economy and benefit the people of Ukraine.”

The Chairman of the Board of Directors of Burisma Holdings, Mr. Alan Apter, noted: “The company's strategy is aimed at the strongest concentration of professional staff and the introduction of best corporate practices, and we're delighted that Mr. Biden is joining us to help us achieve these goals.”

Mr. R. Hunter Biden is one of the co-founders and a managing partner of the investment advisory company Rosemont Seneca Partners, as well as chairman of the board of Rosemont Seneca Advisors. Mr. Biden has experience in public service and foreign policy. He is a director for the U.S. Global Leadership Coalition, The Center for National Policy, and the Chairman's Advisory Board for the National Democratic Institute. Having served as a Senior Vice President at Maryland Bank N.A., former U.S. President Bill Clinton appointed him an Executive Director of E-Commerce Policy Coordination under Secretary of Commerce William Daley. Mr. Biden served as Honorary Co-Chair of the 2008 Obama-Biden Inaugural Committee. Mr. Biden is also a well-known public figure. He is chairman of the Board of the World Food Programme U.S.A., together with the world's largest humanitarian organisation, the United Nations World Food Programme.

The Dnieper-Donets basin, known commonly as the Donbass and regarded as a historical, economic and cultural region of eastern Ukraine and southwest Russia, covers the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine, and also Rostov oblast of the Russian Federation.

The people of the Donbass, the country's gritty industrial region in the east, were not naive. They realised that gas pipelines crossing the border with Russia and the shale gas fields near Slovyansk - with a potential reserve of about 3 trillion cubic meters of gas - were the cause of constant tension between Russia and Ukraine.

But with pipes in their backyards or running right next to their homes, with their feet firmly on ground which stands over a vast shale deposit, they knew the struggle was not really over Ukraine itself. They were in the middle of a war about energy.

Depending on the political winds blowing between Kiev and Moscow, Gazprom cut off natural gas to Ukraine or turned it on again. The shale gas is an important potential source for Ukraine and possibly southeastern Europe. If it proves possible to tap, Ukraine hopes this supply would undercut Gazprom's monopoly, a move which could change Europe's energy map and its political contours as well.

The Donbass, currently the most densely populated of all the regions of Ukraine - excluding the capital city of Kiev - lies in the hotly contested eastern part of the country and where a bloody civil war is raging, and is the major oil and gas producing region of Ukraine accounting for approximately 90 per cent of Ukrainian production and according to E.I.A. may have 42 tcf of shale gas resources technically recoverable from 197 tcf of risked shale gas in place.

The Ukraine government has decided to let no crisis or rather civil war go to waste, and while the fighting raged all around, Ukrainian troopers were helping to install shale gas production equipment near the east Ukrainian town of Slavyansk, which was bombed and shelled for three months and all but destroyed.

The people of Slavyansk, which is located in the heart of the Yzovka shale gas field, staged numerous protest actions in the past against its development. They even wanted to call in a referendum on that subject. Environmentalists are particularly concerned with the consequences of ‘fracking', the method used for shale gas extraction, because it implies the use of extremely toxic chemical agents which can poison not only subsoil waters but also the atmosphere. Experts claim that not a single country in the world has invented a method of utilisation of harmful toxic agents in the process of development of shale gas deposits. Countries like the Czech Republic, France and the Netherlands have given up plans to develop shale gas deposits in their territories. And so did Germany.

Which clearly makes Ukraine, potentially the last place with massive shale gas deposits and no drilling ban, quite valuable to those who want to develop a major source of shale gas, one which reduces Europe's reliance on Russian gas even more, yet one the future of which depends on one simple question: who controls eastern Ukraine ?

Because what better way to accelerate ‘next steps' than to start drilling for gas in the middle of the Donetsk republics as a civil war is waging in all directions, and where public mood has shifted decidedly against the local ‘separatists' in the aftermath of the MH-17 tragedy ?

Perhaps Ukraine does not need Russia to take it down. The Kiev government is doing quite well destroying itself, most recently with a new tax code which doubles taxes for private gas producers and promises irreparably to cripple new investment in the energy sector at a time when reform and outside investment were the country's only hope.

On 1 August 2014 President Poroshenko signed off on a new tax code which effectively doubles the tax private gas producers in Ukraine will have to pay, calling into question any new investment, as well as commitment from key producers already operating in the country.

The stated goal of the new tax code - enacted by the Verkhovna Rada, the Parliament, on 31 July 2014 with more than 300 votes - is to raise US$ 1 billion, of which US$ 791 million would go to fund the war effort in eastern Ukraine.

According to the local media, the new code will remain in force until the end of 2014 during which time gas drillers will be required to pay 55 per cent of their subsoil revenue for extracting under five kilometres. This is up from 28 per cent - which is a significant disadvantage to producers. Additionally, for any extraction beyond five kilometres, the tax will be 28 per cent - up from 15 per cent. This is a considerable improvement on an early version of the bill which called for a 70 per cent tax on gas extraction.

Ukraine may have some of the most attractive gas prices in the world - the only thing which could have possibly lured investors there - but the new tax law renders this irrelevant, especially considering that in European countries, the tax does not exceed 20 per cent.

The oil sector will also be hit with the new tax code, which increases rates to 45 per cent for drilling under five kilometres-up from 39 per cent. But it is the gas tax hike which will really cripple potential investment in Ukraine.

Private gas producers lobbied energetically against the new tax code, arguing that it will crush investment and force investors to re-think their commitment to Ukraine. They also argue that it benefits some members of the political-business élite, and has nothing at all to do with funding the war effort in the east. Instead, it is the next phase in the battle among energy oligarchs to secure their interests in the dynamic political arena shaping up after the fall of President Yanukovych.

In an open letter sent to Parliament on 29 July 2014 a group of private producers stated: “The draft law may lead to a rapid increase in the tax burden on private gas producing companies, a significant decrease in project cost effectiveness in general (up to closing down due to unprofitability) and a general decrease in attractiveness of the Ukrainian market for foreign investors.”

The law is regarded by the oil men as dangerous to the long-term security of Ukraine. It adds little to the budget and discourages drilling and investment in the upstream oil and gas sector, as well as calls into question the ability to invest in Ukraine at all. Not many corporations would want to invest in a country which arbitrarily punishes investors who are creating value by increasing reserves and production, or who are paying taxes and employing hundreds of thousands of people. No one will invest in an industry with the risk that taxes will be double or triple within a few months, said the oil men. They pointed out that the bill had been drafted with a view to favouring key beneficiaries: energy magnates Rinat Akhmetov and Ihor Kolomoyski, who “either own oil or mining assets that were taxed immaterially and punitively taxed gas producers.”

At this point one could be entitled to doubt the sagacity of the Australian Prime Minister, Tony Abbott and his ministers. They might never have asked themselves whether the ‘Ukrainian crisis' revolves around something that the American administration may value more than anything - despite its rhetorical proclamations about freedom for everyone and from everything.

What is at the foundation of the American administration in Kiev is nothing but a profound thirst for oil and the fear of losing the battle with Russia on the supply of natural gas to the European market.

It was known, perhaps even by some people in the Australian Establishment, that Russia had been engaged for years in the construction of South Stream. The pipeline was core to the larger battle being fought over the European markets between American and Russian interests. It may even have been a motivation behind Russia's annexation of Crimea.

At the end of the above summary there remains to contemplate the misfortune of a big loser, Ukraine.

Before the Maidan coup, Ukraine - though admittedly plagued with problems - was a whole, functioning and relatively peaceful nation.

Now, over one year later, Ukraine has a civil war in the East, a bankrupt economy begging for handouts, a government run by foreigners and an ex-U.S. State Department official, a Verkhovna Rada full of shady Nazi overlords, an Azov battalion run by the brutal oligarch Kolomoisky, a Crimea ascended to Russia, a Security Services run by the C.I.A., and so many more problems I would need many pa pages to list them all out.

And what awaits Ukraine in the future ? Possibly, a crushing E.U. ‘austerity' which will make what Greece went through look like a picnic … and no more gas. Ukraine has been officially frozen out of the gas game.

Are ‘western' sanctions over Russia's support of eastern Ukraine separatists, the declining price of oil, and the sharp decline of the rouble causing significant enough pressure on the Russian economy to change Putin's stance on the Ukraine ?

In a recent report the United Nations estimated that of the 454,000 people who had left Ukraine by the end of October 2014, more than 387,000 went to Russia. The eastern Ukraine problem is defined by the fact that many people in the region feel closer to Moscow than Kiev. However almost 400,000 refuges, independent of whether they are ethnic Russians, is not what Russia wants at a time when it has economic problems.

Instead of a major change in relations with Ukraine ‘the West' is likely to watch President Putin as he reinvigorates relations between Russia, China, India, and even Iran. The way Putin is responding to the ‘western' sanctions, falling oil, and the declining rouble is going to ensure that Russia is less dependent on ‘the West' in the future. History may show that the lesson of the ‘western' sanctions was to strengthen the rest of the world and reduce America's influence on Asia.

The examples of this happening already are many, including Russia's multi billion dollar oil deal with China, and its support of India infrastructure and power plant construction. In December 2014 Putin made a one day stop in India to cement the deal to use Russian resources to build 25 power plants in India.

Putin recently, mentioned that Russia expects to secure a “role of a reliable energy supplier to the Asian markets.” “Historically, Russia has exported most of its hydrocarbons to the West.” but that was about to change.

As President Putin has observed, “the European consumption is increasing too slowly ... at the same time, the economies of Asian countries are growing rapidly.” That is another way of saying that he is detaching Russian economy from ‘the West' - which, in the end, maybe the true consequence of sanctions.

* * *

At mid-January 2015 Russia executed a bold move, one which was largely unanticipated. It shows the level of disgust with both the coup-based Ukraine government and the European Union leaders and their small state followers.

Ukraine is finished as a supply route for Russian natural gas headed for European Union countries. The E.U. countries used to receive 25 to 30 per cent of their natural gas from the Ukraine pipeline. In the future gas transiting Ukraine would be diverted to the recently announced Russia-Turkey pipeline. The Turks would provide a portal at the Greek border where Europeans can purchase natural gas. The Blue Stream pipeline is intended to be completed in 2017. Of course, the E.U. countries will need to build the pipeline infrastructure from the Turkish portal to various European countries.

Russian natural gas delivered to Europe via Ukraine had been reduced by 47 per cent in 2014. The end of Ukraine transit will eventually eliminate US$ 1.7 billion a year that Ukraine earns from hosting the pipeline.

The Ukraine gas pipeline has been a headache for Russia for years. The Russians claim that Ukraine siphoned off gas from amounts intended for Europe. The issue came to a head in 2006 with Ukraine officials admitting that they had taken gas intended for Europe.

As the conflict between Russia on one side and the E.U. and the American administration on the other festered, a number of suggestions were offered as replacement alternatives for Russia's natural gas. But much of it was wishful thinking according to a revealing comment made by Germany's Economy Minister in March 2014: “There is no sensible alternative to Russian gas to meet Europe's energy needs.” German Economy Minister Sigmar Gabriel had said. “Many people acted as if there [were] plenty of other sources from which Europe could draw its gas, but this is not the case.” Gabriel had warned an energy forum organised by the Neue Osnabruecker Zeitung on 27 March 2014. Will Europe be able to find a sensible alternative before the gas shifts from the Ukraine pipeline to the Russia-Turkey pipeline in 2017 ?