A Reality Check On Farmer Suicides

By Moin Qazi

31 October, 2015

Countercurrents.org

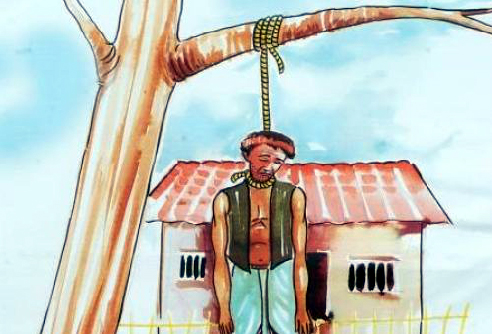

In the last 20 years, nearly 300,000 farmers have ended their lives by ingesting pesticides or by hanging themselves. Maharashtra state - with 60,000 farmer suicides - tops the list. The suicide rate among Indian farmers was 47 percent higher than the national average, according to a 2011 census. Forty-one farmers commit suicide every day, leaving behind scores of orphans and widows. In a country where agriculture remains the largest employment sector, it contributed only 13.7 percent to the GDP in 2012-13.

Vidarbha falls in a rain-shadow area. . The Vidarbha Irrigation Development Corporation had once about 100 irrigation projects in the pipeline — sadly, most of them still remain on paper. It is also a fact that just 15% of the farmers are covered by the crop insurance scheme. However, for a farmer to be eligible for insurance, a district to which she/he belongs must be declared drought-affected, a factor that adds to the problems. In 2005, the Tata Institute of Social Sciences did a study of farm suicides. It found that the phenomenon was not restricted to any category of landowners. But the concentration of suicides was greater among small farmers (who owned up to five acres) and middle farmers (who owned more than five acres but less than 15 acres). And the Centre’s 2008 loan waiver applied to farmers who owned up to five acres.

The existing lending network in rural India, whether we like it or not, is still dominated by moneylenders. Their pricing of risk is premised on hand-me-down philosophies that revolve around predictable patterns of agriculture—a two-crop harvest of rice and wheat (both of which have a guaranteed price from the Central government) and associated income cycle inter-twined with the monsoon.

So, the farmer borrows ahead of the harvest and repays immediately after its sale. In this situation the only variable is the monsoon, the vagaries of which are also fairly predictable, leaving the farmer and moneylender fairly aware of the pricing risks. Since the ticket size of these loans is relatively small, say Rs25,000-50,000, the conventional usurious pricing at 40-50% works reasonably well to keep the farmer just sufficiently above water and the moneylender in good fettle. Now, in this situation if you introduce the opportunity of using hybrid commercial crops or squeeze in a third crop, then the situation changes dramatically, as not only does it introduce new variables, but also increases the downside risks for the farmer dramatically. The farmer’s math shows that upping his investment (average loan size for this class of farmers is Rs50,000-100,000) would bring better gains, and eventually a faster way to economic prosperity.

A perfectly valid commercial decision, but it overlooks the fact that the moneylender does not have the wherewithal to price this enhanced risk; the moneylender would simply increase the collateral or the interest rates—in either instance the downside risk goes up linearly for the farmer. While in good times the farmer does reasonably well, the downside is a sure-shot guarantee of falling into a debt trap.

This mismatch of willingness to take a commercial risk and inability to price it economically is what lies at the heart of the frustrating issue of farmer suicides. On the other hand, an institution following commercial principles that allow for hedging the risk and thereby reducing the odds in the case of a downside risk of, say, a monsoon failure and consequent drought or a pest attack (some of the hybrid seeds are highly vulnerable to such contagion).

Unfortunately at the moment, the existing institutions that operate as an alternative to moneylenders are incapable of stepping in to fix the problem. What complicates matters is the varied topography and seasonal variations across the country, which inhibit government-backed institutions that tend to follow standard templates. The solution is local, almost tailor-made in theory for the emerging microfinance institutions to be a possible alternative. Easier said than done, though, because the scale of these loans is too large, but may be the microfinance template of operating in niche and local areas could be a better alternative to pursue in pricing the risk.

Access to finance is critical for a country’s development - it is as much a part of a country’s basic infrastructure as access to roads, or electricity, or the Internet. Ample evidence indicates that economies with deeper financial sectors and well-functioning financial systems perform better.

Moreover, access to finance is an important contributor to inclusive development. Poor households in particular need access to a broad range of financial services — savings, insurance, money transfers, and credit — in order to smooth consumption, build assets, absorb shocks and manage risks associated with irregular and unpredictable income. Without access to good formal services, the poor must rely on the less reliable and often far more expensive informal sector.

And they have to deal with an assorted bunch of predators—moneylenders, creditors and others .Once known as white gold because it was such a profitable crop, cotton is no longer a money-making venture in India. The growing sophistication of agricultural methods has made cotton farming more and more expensive over the decades, and the Indian government has gradually moved away from subsidizing farmers' production. Cotton is more vulnerable to pests than wheat or rice, and farmers are forced to invest heavily in pesticides and fertilizer.

We can think of reviving cottage industries or even subsidising them but there are no markets till we introduce the hub and spoke model and make villages as wealth creators, there will be no impetus to the rural economy. Everybody goes after the lowest hanging fruits. An industry has a powerful gravitational pull. Schools follow, markets starts growing, transport starts plying generating employment for labour and scope for business. Hospitals and clinics usually follow an economically growing centre. This is the way China and Korea have overcome poverty

For every Indian farmer who takes his own life, a family is hounded by the debt he leaves behind, typically resulting in children dropping out of school to become farmhands, and surviving family members themselves frequently committing suicide out of hopelessness and despair. The Indian government's response to the crisis—largely in the form of limited debt relief and compensation programs—has failed to address the magnitude and scope of the problem or its underlying causes.

Moin Qazi is a well known banker, author and Islamic researcher .He holds doctorates in Economics and English. He was Visiting Fellow at the University of Manchester. He has authored several books on religion, rural finance, culture and handicrafts. He is author of the bestselling book Village Diary of a Development Banker. He is also a recipient of UNESCO World Politics Essay Gold Medal and Rotary International’s Vocational Excellence Award. He is based in Nagpur and can be reached at [email protected]