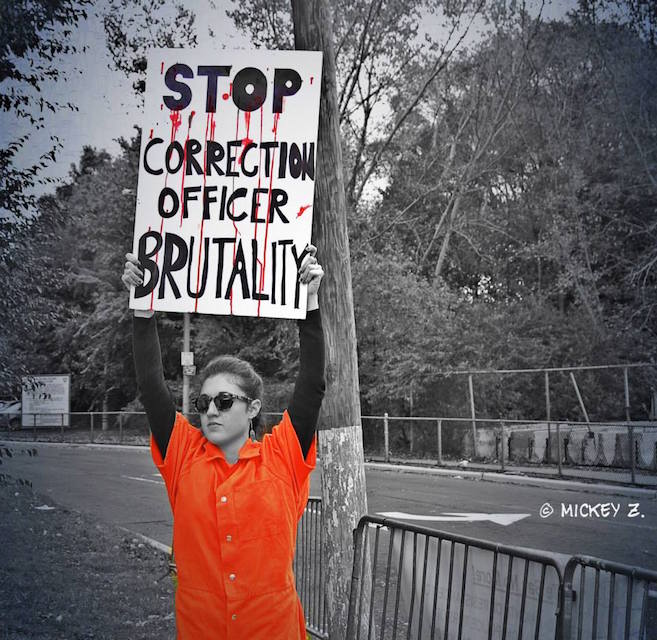

Cecily McMillan On Prisons, Profit, Protest, And Privilege

By Mickey Z.

17 November, 2014

World News Trust

Photo credit: Mickey Z.

“If you can wrap your mind around the reality that I’m a violent felon but still see me as a human being, then you have to do the same for everyone else.” - Cecily McMillan

It’s far to early to access the legacy of Occupy Wall Street but, from my personal experience, one thing is undeniable: Crucial and enduring connections were made. It is thanks to OWS that I know Cecily McMillan and was thus able to have and share the conversation below.

Cecily is a graduate student at the New School for Social Research, a union organizer and a former Occupy Wall Street activist. On March 17, 2012, the six-month anniversary of the OWS encampment, McMillan was arrested, sexually assaulted, and beaten by members of the NYPD. Nonetheless, in Spring 2014, McMillan was unjustly convicted of felony assault of a police officer and faced seven years in prison.

Following an international leniency campaign, McMillan was sentenced to 90 days at the Rikers Island Correctional Facility. In July 2014, she was released on good behavior after serving 58 days.

Since her release, Cecily has organized and advocated for reform at Rikers and the abolition of mass incarceration at large. She is also writing a memoir of her journey towards activism, her participation in OWS, and her experience in jail.

Cecily and I recently met up in NYC’s Union Square Park to discuss some of these issues. Our conversation went a little something like this…

Mickey Z.: In the Land of the Free™, one out of every 31 adults is in prison, on probation, or on parole. Based on your experiences, what do you think the “other 30” would be most surprised to learn about the prison-industrial complex?

Cecily McMillan: I guess it’d be who’s actually in jail and why. Many people assume that if you’re in jail -- especially on Rikers Island -- you’ve done something wrong, whereas most of the people on Rikers have not been convicted of anything. It’s often a matter of very weak accusations made against them coupled with a legal system that favors prosecutors.

MZ: Prosecutors over judges?

CM: Yes, the power is no longer in the hands of the judges. It’s really the prosecutors who execute plea bargain negotiations. This means some people are there -- some of them for up to seven years -- before they even get charged with anything. It’s not that seven years later they suddenly have a strong case against them. Many of the people in Rikers are waiting for a plea bargain to come down low enough that it’s in their best interest to cop a plea.

The system is stacked against them -- especially if it’s going to a jury trial in Manhattan. Of the 160 or so jurors I’ve seen over the course of two trials, only a handful have been Black or Latino. So it’s not going to be a jury of their peers, they understand this. Also, you’re not going to have very qualified representation because public defenders are overworked and underpaid and there’s already the stigma that you’ve done something wrong.

MZ: What role do grand jury indictments play in the system you’re describing?

CM: People don’t really understand that all the evidence is brought before the grand jury and the state can spin whatever story they want. Almost never -- less that 1 percent of the time -- does the defendant step up to tell their side of the story because whatever you say there can and will be used against you in a trial -- even though most of them will never go to trial. So it’s a weird dance, but really all a grand jury has to do is say that -- given the evidence -- it’s possible that somebody committed a crime. From the get-go, you are considered guilty until proven not guilty. You’re never innocent. Just the fact that you had to go on trial criminalizes you.

MZ: I’m guessing very few of those charged with crimes actually go to trial.

CM: Less than three percent of felony cases go to trial and you can guess the skin color of defendants that would go along with that percentage. But skin color is the marker of the real issue here -- it's a matter of class privilege. You have to have a lot of money to stand up and say "I'm innocent" in this country. The basic fact is, most people can't afford the fight.

MZ: Which brings us back to your initial point that most folks would be stunned to learn how few people in Rikers have been convicted of anything.

CM: Roughly 90 percent of those in the “sentencing area” are detainees awaiting trial which, as I said, means waiting for a plea bargain that is amenable to them.

MZ: In your particular case, once you were sentenced, where did they send you?

CM: I was sent to a sentencee dorm and it’s important to note that my charge -- a violent felony -- was the highest charge of the 150 or so women I met during my time there. If not for the color of my skin, I’d likely had been in Bedford for four or five years. So, while I was the “most dangerous” inmate in my entire dorm, most of the other women there could be summed up into three categories. The most prevalent is arrests associated with a drug addiction, drug dealing, or a psycho-social disorder, e.g. alcoholism, anxiety, bipolar depression. I would estimate 60 to 70 percent of the women fit into this broad category -- something even the most basic mental health or rehabilitative program could’ve prevented.

MZ: Did women such as this discuss their situations with you?

CM: Yes and they made it quite clear that they do want help. Some said that, even though it was one of the worst ways to do so, at least their time in Rikers helped them get clean. There were often stories about having to deal drugs because without the skills this society values, it was the only way to feed their families -- especially if the father of their children was also in Rikers. That particular scenario often resulted in two parents timing a call to their child, coordinating it from one Rikers phone to another Rikers phone to an outside phone. That was very, very common.

MZ: What are the other categories?

CM: The second category -- maybe another 15 to 20 percent -- were those who broke probation. In one case, a woman lost her house and didn’t report it. Many others lose their job but also don’t report it. After the way these folks have been treated -- after the way they’ve been targeted, harassed, beaten, brutalized, oppressed by the police -- they aren’t exactly in any hurry to pick up the phone and call their probation officer. You’re supposed to report any breaking of the terms of your probation but they’re scared and they’re right to be scared.

MZ: And the remaining 10 percent or so?

CM: The majority of them were sex workers -- women that sold their bodies in order to take care of themselves or their family. As you can see, the bulk of the women are there as a result of lack of opportunity. Considering that it costs an estimated $160,000 a year to keep one human in Rikers versus $4,500 spent on each child in public education, it doesn’t make sense, no matter how you slice it. Fiscally or morally, it makes no sense to spend that kind of money to put people in need away without access to drug programs, domestic violence programs, or adequate mental health care.

MZ: With America’s prison population rising 700 percent since 1970 -- far outpacing general population growth -- what role do you feel profit plays?

CM: In the South, we have private prisons. My brother’s in a private prison; he’s spent most of his adult life in a private prison. There, imprisonment does make more fiscal sense for whomever it’s benefitting. Rikers is just a black pit of our taxpayer dollars whereas in the South, it is literally entrapment and slavery.

Regardless if it’s public or private, however, people end up there because they are not seen as valuable participants in this plutocracy. I say plutocracy because voting is not the primary means of political participation but, instead, the primary means is buying policy. It’s buying politicians.

MZ: That leaves a whole lot of us out in the cold.

CM: Citizenry is not defined by your birthright but, instead, by your “consumer right.” Since there are folks who can no longer afford to participate in our society -- which means buying and selling things, affecting the market in a way that makes them a valuable member of society -- they get swept up and put somewhere else so we don’t have to deal with them.

MZ: But they can still be used to make someone a profit.

CM: As dirty as this sounds, private prisons offer a way to “re-purpose” those who can’t afford to participate in our consumer state. It’s slavery. They are basically being told that they’d be more useful if forced to do hard labor to “earn” their welfare, so to speak.

MZ: Activists are often accused of only focusing on what’s wrong and indeed, the picture being painted here is bleak. What do you feel someone reading this article can start doing -- right now -- to make a difference on this issue?

CM: I think, first and foremost, a big thing any individual can right now, in this moment -- take 30 seconds -- is to reconfigure your mind away from the concept of “criminal.” People reading this might not want to accept that I am a violent felon because, if they see me like that, it upsets their sense of security. So, as you read this, wrap your mind around the reality that I’m Cecily but I’m also a violent felon, I have a case number, I was convicted by a jury of my peers and sent to Rikers where I lived and survived for two months. If you can know all that but still see me as a human being, then you have to do the same for everyone else.

Almost every other person in Rikers had a story just as twisted and fucked up as mine but it was a lot more normalized because of the color of their skin. What we all must do is see that whether or not someone is in jail, whether or not they committed a crime or were targeted by the police, they’re people. They’re people first. If we’re going to reorient this plutocracy back towards democracy then we have to view every single person in this country as a person with rights who deserves to be treated like a human being.

MZ: Indeed, major changes often grow out of seeing the world with new eyes. As for engaging in collective and street efforts, can you tell us about the #ResistRikers campaign?

CM: We can all read The New Jim Crow or my New York Times op-ed or this interview and believe we have some kind of empathetic understanding of what Rikers is. But Rikers is the literal sixth NYC borough, housing an entire underclass. The closest I can get you to begin understanding what this means is by coming out on Saturday, Dec. 6 at 3 p.m. EST at the Rikers Island entrance sign. You will literally stand at the doorstep of Rikers, look across that bridge, and realize you can’t go there, you can't go see an entire class of people locked behind razor wire and bars. You can't hear their voices, their cries. You can't touch them, hold them. The bridge between you is a crushing characterization of how many are left out of our society, taken away -- in some cases, never seen alive again.

You’ll see the corrections officers’ cars speed by and you’ll see ambulances coming and going; people might be dying as you’re standing out there with us. I feel this experience will help you realize that being on the outside and having never been in there is such an incredible privilege that you simply have to do something about it.

MZ: What can we do about it?

CM: As part of the #ResistRikers campaign, we’re trying to set up an ad hoc community review board. Local councilpersons and state senators have been calling for such a review board for years. In fact, after the Attica uprising, the Board of Corrections (BOC) was supposed to be a publicly controlled community review board. Instead, we have banking officials sitting on the board.

On Dec. 6, you’ll get to meet and hear people speaking out for themselves, for loved ones in Rikers, and calling for the creation of a decision-making body of the people, by the people, and for the people. That’s the people on the outside and the people on the inside. We’re giving a voice to those inside who are left without a grievance process, without adequate medical care, without protection from sexual and physical abuse. We’re setting up a bridge of communication between the inside and outside to call for the BOC and DOC (Department of Corrections) to be held accountable. Maybe one day, we'll even take that bridge.

MZ: How can readers learn more, get involved, and/or contact you?

CM: Visit ResistRikers.wordpress.com for updates and information on how to get involved. We hold open organizing meetings and are planning another rally at Rikers on Dec. 6th. You can also check for updates on Facebook & Twitter by searching #ResistRikers. I hope to see y'all there!

Mickey Z. is the author of 12 books, most recently Occupy this Book: Mickey Z. on Activism. Until the laws are changed or the power runs out, he can be found on the Web here. Anyone wishing to support his activist efforts can do so by making a donation here.

©WorldNewsTrust.com

Comments are moderated