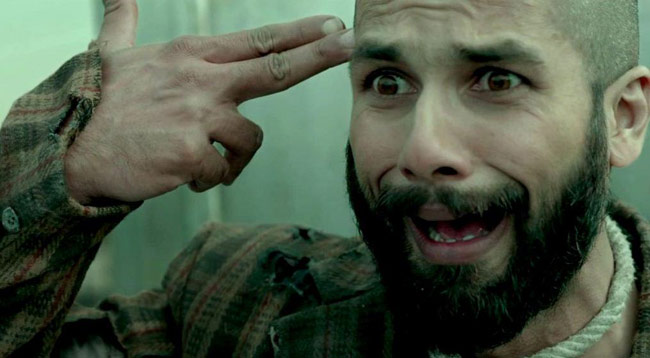

'Haider' Review

By Iymon Majid

03 October, 2014

Countercurrents.org

“What happened in Kashmir is a very human tragedy, but no one is talking about it. But once you talk of it, you are released from it. What I am saying is the truth. (Emphasis added).It should be like a balm on a wound.” Vishal Bhardwaj.

The truth is Kashmir is a disputed territory. Still when Haider opens, a blatant lie is told to the audience. Srinagar, India. 1995. Such a statement makes the film deeply political. Lines are drawn. A stand is taken that Srinagar is (integral) part of India. What kind of truth is then Bhardwaj telling us? Or is he just telling us a selected version of truth?

Of course he is telling us that Kashmiris have disappeared, they have been killed in police custodies, they have been brutally tortured, and there is fear in their hearts even to enter their own homes. Thus in the human rights framework the film does a commendable job. But Kashmir is not a Human rights issue; instead it is a political one. By making Human rights the core of the film, the filmmakers are telling us that the moment these human rights abuses are done away Kashmir will be peaceful and the conflict will be over.

At the political level, however, Bhardwaj looks at the tragedy of Kashmir through a definite lens which is Indian. It is not ultra-nationalist but it is more akin to the view of Indian liberal academicians. They decry human rights violations but when it comes to overall Kashmir dispute they believe it is a part of India.

Thus Haider becomes a revenge tale so becomes Kashmir. On one side is Haider whose father is pro-militant and on his opposite side is Khurram—a pro-India Kashmiri politician and an Ikhwani. He is power hungry. He looks at his sister-in-law with lustful eyes. He kills people for money.

It is a story of one Kashmiri versus another Kashmiri. It is a film where you don’t see an Indian army man killing a non-combatant Kashmiri but only a Kashmiri killing another Kashmiri. Numerous scenes are testimonial to that. It is the police (Kashmiri) which is doing custodial killings whereas Indian military only forces militants and their sympathizers to chant Jai Hind and sometimes tortures them. The cruelest character in the film is a Kashmiri which is untrue because if you ask any Kashmiri he will answer ‘Army woul.’

Haider is a subtle way of demonizing Kashmiris in the eyes of the Indian audience and telling them that the armed insurgency is Kashmir’s own mess. Telling them through the Army that even Ikhwanis wanted freedom; freedom from militants. I couldn’t understand why the two Salmans were obsessed with Salman Khan. Is the film trying to make a statement that the Kashmiris who collaborate actually worship India because of its movies, a more liberal culture or freedom?

The film consciously tries to show what fits the broad narrative of Indian psyche: Ok a few glitches have happened in the form of human rights abuses but they are pardonable.

For many of us (Kashmiris), there seems little left to say about Kashmir by the Indians, but always there is hope some might tell the truth which Bhardwaj had invoked months ago. But ultimately what we receive is a figment of the truth. We say Kashmir is an occupied territory of India. It has to be said for the first time, and possibly again and again. The question is to challenge the grand narrative of Indian occupation but what we are told, instead, are human rights violations. It is necessary to pluck out the root then the nature will take its own course and leaves will die.

The truth is that films like Haider are more dangerous than say a certain Maa Tujhe Salaam because they systematically redraw the lines. It works on the Gramscian level. Audience is told that the problem is only human rights violations but not the occupation.

The one question I am grappling with is the status of Haider the character as Mujahid or militant. What should we call him? By focusing completely on the revenge the filmmakers have belittled the sacrifices of thousands of Kashmiris who were and are out there fighting the Indian occupation. Thus Bahradwaj and Basharat Peer (co-writer) have magnified a miniscule element of the Kashmiri society that is revenge and have painted the whole struggle of Kashmir with that brush. It is a very elite reading of the Kashmiri conflict. A person who takes revenge is a murderer and not a sacrosanct Mujahid or militant.

In the cinema hall two incidents stand out. One was the scene when the crackdown is announced through the Masjid loudspeakers, the girl sitting next to me asked her friend what is a crackdown? Second when the scene where the man is afraid to enter into his own house. The scene is disturbing. But the audience laughed as if some comic scene was playing.

Haider is certainly a film for them.

Author is a Research Scholar in the Department of Political Science at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.

Comments are moderated