White Feminists/Black Blobs

By Mara Ahmed

21 March, 2016

Countercurrents.org

My friend expressed her strong visceral reaction to the five anonymous blobs. She was referring to a photograph I had posted on social media, in which I stood with five women wearing the niqab, at a conference in Upstate New York. My white feminist friend was convinced we were witnessing oppression. She was particularly galled by the fact that these women were academics. She mentioned how Camille Paglia, Betty Friedan and Hillary Clinton have interesting interactions with strangers because we all know what they look like. How are we supposed to communicate with blobs?

One of the formative words of my childhood is the Urdu word meyana ravi which means the middle path or the way of moderation. My mother invoked it frequently by reminding us that it was a concept loved deeply by the Prophet Muhammad. He lived by it in both small and monumental ways. For example, his advice to eat with temperance, just short of satiating one’s hunger, always struck me as universally profound. Islam’s take on wealth is equally sensible. Although charity is a religious obligation and humility is part of Islam’s DNA, one is urged to live well, meaning no ascetic renunciation of worldly pleasures, no monastic reclusion, no self-imposed austerity. Every society exists along a normative socio-political spectrum, but within the prevalent moral and legal code, we are free to exercise our judgment and express ourselves fully. The golden rule in the midst of such freedom is moderation.

When I walked into a symposium about cultural identity and religious beliefs, organized under the aegis of interfaith dialogue, my thoughts returned to meyana ravi and its centrality in Islam. University professors and educators from Muslim countries had been invited to present their papers. Most of them were from Saudi Arabia and the majority women. I am familiar with the Saudi abaya, a black overcoat worn on top of clothing, not unlike a Moroccan djellaba or a long kaftan, but I was taken aback by the full facial veiling. I couldn’t help but think what a severe take that was on modesty. I felt for the women as the room was uncomfortably warm. One of them looked at me and laughed as she tried to fan herself with the lower section of her veil, a moving part that fell over her nose and mouth. As we went around the room and introduced ourselves, it became clear that many of the men at the symposium were not educators. They were either the husbands or sons of the female professors. In Saudi Arabia, women are not allowed to travel alone. At lunchtime, the women didn’t join the rest of the group. They found a private room where they could take off their veils and eat comfortably.

The papers that were read at the conference were structured around a utopian Islamic paradigm which had very little to do with reality. For this reason, they were almost entirely indistinguishable. They quoted freely from the Quran, stressed the necessity to respect other religions (there is no compulsion in religion), and advocated compassion and tolerance towards religious minorities according to Islamic protocol. The discussions sparked by these papers were more informative. They used culture and religion interchangeably, thus anchoring “Muslim culture” to one specific way of being, which because Islamic, was clearly the best.

An Indonesian professor intervened with a thought-provoking presentation, in which he stressed the idea that culture was human-made and therefore not monolithic. Religion outlines certain basic values which culture subsumes. As an example, he offered the basic tenet of modesty in women’s clothing, which meant that women shouldn’t go around wearing bikinis but, within reasonable parameters, they could decide what modesty meant to them. This argument was followed by a short deliberation on how women should dress and what the Quran and Sunnah reveal on the matter, but some of the women brought the debate to a felicitous close.

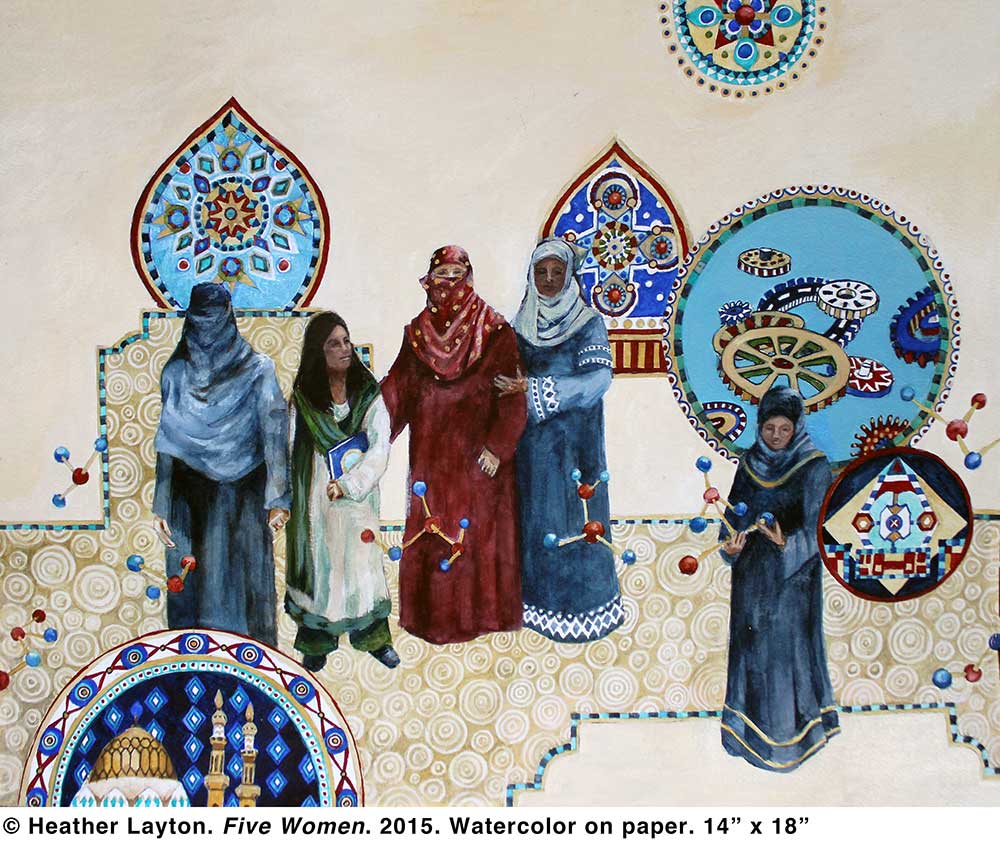

As I got to know the women more, the stark visuality of the veil began to wear off. They greeted me with kisses on the cheek, very similar to how the French se font la bise. They took selfies with my Bosnian American friend and I, and were keen to post everything online. I don’t cover my hair and my friend wears a hijab but does not veil fully. They didn’t seem to have a problem with either one of us. I noticed the close relationship between one of the women and her teenage son, who had taken time off from college to accompany her on this trip. They were academics, mothers, opinionated Muslims, women of color, finicky dressers, social media aficionados, and our sisters in the struggle against patriarchy.

The struggle against patriarchy, that’s what I kept coming back to - how it is twofold for women who belong to disenfranchised communities. On the one hand we must contend with white men in suits, with long histories of imperial profiteering, sitting calmly in boardrooms, instituting laws that control the Maghrebian woman’s body. We have white women who in their haste to diagnose oppression, marginalize further by dehumanizing and isolating what is not in line with their ideas of female emancipation. Then we have the struggle within our own communities, where patriarchy, conservative tradition, and autocratic political structures have brewed a lethal mix. These factors are not disconnected from history and global politics of course. Saudi Arabia is a particularly good example of how the West remains complicit in the repression of Arab self-expression. Close military ties between the United States and the Saudi regime ensure just that.

The obvious links between staggering Western wealth and centuries of imperial conquest and plunder are not mentioned in polite society. Yet there they are. Colonialism reinforced and intensified patriarchal structures in colonized lands and present day imperial wars continue to perpetuate that status quo. White feminists tend to overlook these interdependencies, i.e. some of the economic, legal and sexual freedoms enjoyed by Western women are an indirect result of imperial expansion and profit. These disparities are not natural, they have to be maintained by military force and tyrannical financial structures.

How we dress is an important signifier of identity. In her email, my friend kept referring to the veiled women’s fashion choice and how she had more sympathy for the hijab versus the niqab. But attire goes beyond fashion. It is intimately linked to how we want to project ourselves in the world, it can embody religious or cultural affiliations, it can speak of race, gender and economic class, it provides functionality and protection. The depersonalization of the niqab or burka is often pointed out, but perhaps it is no more homogenizing than the cheap, ready-to-wear clothing manufactured in Bangladesh and Vietnam, under precarious conditions, and thrust upon us by fashion retail every single season.

In order to delve more into covering up and how it interacts with identity, I interviewed another white friend of mine, an activist whose politics aim to be trans-inclusive and whiteness-decentralizing. She started wearing the hijab six months ago. She talked about unquestioned whiteness (accompanied by unquestioned privilege) versus contentious whiteness (which includes people of diverse racial backgrounds passing as white). As a trans woman and a white hijabi, she finds herself mostly on the side of contentiousness – whether it be whiteness, Muslimness or femininity. On top of practical benefits such as not having to worry about one’s hair, she feels that the hijab provides her a sense of security. She embraces the scarf as a symbol of femininity, as well as the modesty and humility she has learned to associate with Islam, but she doesn’t have much use for its oppressive connotations. How do strangers react to her? TSA agents are obviously interested in inspecting her headgear but generally speaking, reactions to her scarf have been neutral - some antagonism but also incidents of heightened chivalry from men. In any case, she told me she was so over the “mystical powers” of the hijab, she wears it as a matter of routine, a habit, an extension of who she is.

To assume that a piece of cloth wrapped around one’s head can spell the complexities of subjugation (or liberation) is astonishingly reductive.

In the early 1990s, the New York based Pakistani artist, Shahzia Sikander, donned an elaborate lace veil for a few weeks in order to record people’s reactions. What fascinated her was her own relationship to the veil - the sense of security and control she experienced by being able to test society’s behavior, whilst being protected from its gaze.

The principle of the male gaze is a cornerstone of feminist theory. Mary Wollstonecraft, Simone de Beauvoir and Hélène Cixous have written extensively about the duality patriarchy creates whereby woman is positioned as the opposite of man, as his inferior or the other. Woman becomes the object of the male gaze and therefore begins to exist only as a body, not an autonomous being possessing both mind and soul as well as physicality. This objectification places oppressive limits on a woman’s agency and dictates a divide between the private and public spheres. Women need to be contained in private spaces and are banished from or invisibilized in public arenas.

How ironic then that although Eurocentric feminists understand the meaning of the male gaze, they are much less sensitive to the power of their own gaze and the objectification of women they see primarily as bodies, as the physical representation of the backward exotic.

The split between the private and public is meaningful here. As in France, most Western feminists are keen on ejecting the visually non-Western other (women in burqas or headscarves being its most obvious manifestation) from public spaces. It’s as if the liberal feminist imaginary cannot exist in conjunction with an Oriental manifestation of what it might mean to be a woman, unless it is in opposition to it - it must strive to dominate and efface in order to define itself.

It’s important to remember, however, that it is precisely in shared public locations that diverse cultural encounters happen, where we learn to dialogue and function as a vibrant society of equally empowered citizens. My feminist friend thought the women’s niqabs were inhibiting their ability to communicate, but state policing of communal spaces can isolate and exclude in a way that clothing most certainly cannot.

Excluding and alienating for purposes of integration is a pretty obvious oxymoron, yet this type of faulty logic is embraced happily as a manifestation of solidarity. There is a difference between paternalism and solidarity. In the words of Australian Aboriginal artist and activist Lilla Watson:

If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.

Let us strive to learn one another’s histories, cultures, political realities and forms of struggle. Let us have the courage to recognize the racist infrastructure undergirding global power imbalances and our complicity in systems of dominance. Let us forge alliances that are respectful of difference and politically evolved. Gender justice is only one component of the broader struggle for racial and economic justice as well as queer and transgender rights. Let us confront these inequities simultaneously, exhaustively, mindfully. Exclusion is not an option.

Mara Ahmed has lived and been educated in Belgium, Pakistan and the US. An artist and filmmaker, her third documentary "A Thin Wall," about the partition of India in 1947, premiered in the US in April 2015 and was subsequently screened at the Bradford Literature Festival (UK), the Third i Film Festival in San Francisco, and the Seattle South Asian Film Festival. It will be screened in London, Dublin, Brussels and Amsterdam in April 2016. More information at NeelumFilms.com.