Stories From Afghanistan: This Is Not A Place For Life

By Mike Ferner

03 February, 2011

Countercurrents.org

KABUL – The NGO's offices were sparse and well worn, but they bustled with a palpable sense of purpose. Our host's hospitality was unerring. For reasons that will become obvious, we will call him Dr. Ahmed Hasan. Everything else about him and his work is precisely as related.

Dr. Hasan is director of operations for an international Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) providing relief for “Internally Displaced Persons,” (IDPs) or refugees as they were once called. He said he coordinates an agriculture and livestock project, midwifery services, immunizations, women's empowerment, women's shelters and a “weatherization” program that consists primarily of distributing firewood and small, tin heating stoves to people living in mud huts that have blankets for doors.

Since 2002, shortly after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan , the good doctor and his staff have pushed this boulder of aid programs uphill. With each influx of refugees from each new military operation it rolls back down.

The doctor describes one of the three camps in his charge, housing about 1,000 families averaging 7 to 8 people each. The weatherization process provides each family a firewood ration of 120 kilos per month, during the coldest months of the year only. This equals about 10 pounds of wood per day per family for all cooking and heating.

Beyond the director's responsibilities, five more large IDP camps and several smaller ones “house” about 10,000 families, in and around Kabul .

Most people living in Hasan's camp came originally from Pakistan , disrupted by the violence of U.S./NATO campaigns waged against the complex web of groups lumped into “the opposition.” Residents in other camps came directly from the southern and eastern provinces of Afghanistan .

The site is on land previously owned by the Ministry of Defense and allegedly purchased by an Afghan National Army officer whom Hasan says claims authority to remove the families whenever he wants.

Water for these 7,000 people comes from two hand pumps and what UNICEF can truck in. The assumed owner of the land does not allow any drilling for water.

Most of the people in the camp have nothing left back home and don't want to return, Hasan explained. What's needed, he said, is to create a plan to improve their lives, including housing, education, jobs, water and sewer. “It is not sustainable to have them stay in their present conditions, surviving on food drop-offs. They need the other services to be able to work.”

Asked who is responsible for the refugees' desperate situation Dr. Hasan replied, “The United States, Afghanistan , the Taliban and the militias should all be held responsible.”

“The U.S. tells the people, ‘We are bringing security.' The Taliban tell the people, ‘We are bringing security.' The problem is that no one is bringing security. If they keep fighting only, everywhere there will be IDP's.”

“U.S. is responsible even more than the Taliban,” because of its advanced weaponry, numerous air strikes and the large number of nighttime house raids U.S. troops routinely carry out, he added. “I hoped to see things return to peace with the intervention of the U.S. but unfortunately it's getting worse.”

In response to the escalating violence, Hasan's agency joined 28 other NGO's in signing an Oxfam International report titled, “Nowhere to Turn: The failure to protect civilians in Afghanistan. ” While acknowledging that “ AOG (Armed Opposition Groups) continue to be responsible for the great majority of casualties,” t he report also condemned U.S.-NATO night raids and the U.S. practices of arming militia groups and ignoring regulations established to clearly separate humanitarian aid from the military.

In order to “win hearts and minds,” a core principle of counter-insurgency warfare, ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) troops often take a “carrot and stick” approach of mixing military and aid programs. To highlight the problems caused by this practice, the Oxfam report referred to a document adopted by ISAF and the U.N., Guidelines for the Interaction of Civilian and Military Actors in Afghanistan .

That document repeatedly stressed that the line between aid and military operations is not to be blurred, even elevating that dictum to one of its “Guiding Principles.”

“A clear distinction must be retained between the identities, functions and roles of the different entities in order to preserve the humanitarian actors' neutrality . The independence and civilian nature of humanitarian assistance should be clear at all times (importance of the perception by the population/uniform – vehicles – etc.)… only in exceptional circumstances and as a last resort, military assets...may be deployed for the purpose of providing humanitarian assistance.” (Emphasis in original)

Even in the case of the Provisional Reconstruction Teams (PRT), the Guidelines state that “… humanitarian assistance has to be provided only ‘in extremis' and must not be used for the purpose of political gain, relationship-building or winning hearts and minds.” (Emphasis in original)

“Unfortunately,” the Oxfam report stated, “ this distinction has been severely blurred to the point of being unrecognizable to many Afghans, including AOG. …(T)he use of soldiers and heavily protected contractors to implement PRT and other reconstruction and development projects, particularly those which serve counterinsurgency objectives, has also blurred the line between aid agencies and the military.”

Dr. Hasan added, “To those, like the U.S. , who say that an area has to be ‘secured' first by the military before an aid project can be set up, I say this is not acceptable. It is not acceptable to the community. If it is done that way it creates a fragile, unsustainable sort of security. It is better if people negotiate directly with the Taliban for security.”

Describing an approach that would leave General Petraeus, President Obama and nearly all of Congress speechless, the aid director told of his experience in Urozgan Province , where Taliban activity prevented him from starting an aid project.

Instead of waiting for the U.S. to send in an air strike, Hasan said his team met with the Taliban leaders and explained what they wanted to do. “Eventually they told us, ‘Please come and work here.'” The doctor paused briefly and then added, “It is not possible, ever, to first bombard and then send aid. It will not work. Our medical services are open to all. Are Taliban not human beings?”

In remarkably frank words for an NGO aid official, he continued, “Stop funding militias. They are not useful. They bring insecurity rather than security. I will tell you that for security, people are happy with the Taliban more than the militias.”

Voicing an opinion heard in other Kabul conversations, Hasan added, “There is even talk now that the U.S. ‘uses' the insurgency to create a demand from Afghans to stay permanently.”

Several days after talking with Dr. Hasan, a visit to an IDP camp exposed another cost of the war.

My guide and interpreter for the visit was Dr. Rafiullah Ahmadzai, a medical doctor who earned his degree at Kabul University during Afghanistan 's civil war in the mid-90's.

On the dusty, rocky ride out of central Kabul to the camp, the doctor reminisced about the changes he's seen in Kabul over the years. In the last decade his city's population had grown from one to five million. In the mid 20 th century it was a small city known for its shops, architecture and charm, a place where people from several countries in the region went to vacation.

What was one thing he thought his country could really use help with? “Much more education for the Afghan National Army and the police,” the 33 year-old pediatrician replied.

For himself, he said he very much wants to go to the U.S. to further his education with an advanced degree in hematology or public health, adding that his country has a high rate of blood cancers and infectious diseases.

Talk of study abroad ended abruptly when we reached the camp, a monochromatic scene of tents and mud huts extending to a horizon brought up short by the dried mud, smoke, car exhaust and reportedly, the highest amount of airborne fecal matter of any city in the world . Directly across the partially-paved, almost two-lane road, the U.S. was constructing a behemoth of a military base, bordered by a handsome 12 foot-high wall of fabricated stone.

Home for 16 people. photo: Mike Ferner

Established three years ago, Dr. Ahmadzai explained the camp housed about 700 families, ranging in size from five to between 10 and 15 people each.

Back row: Ismail, Faiz Mohammed photo: Mike Ferner

The first person he introduced was Ismail, a tall man of 45 years, sitting on a backless canvas stool, holding a stout cane, blind in both eyes. Asked what caused his blindness he answered simply, “the fighting.” One of his daughters was born missing a kidney and congenitally blind. His wife and their three children live in the camp as they have done for the last two years.

When asked what he hoped the next two years would bring, Ismail immediately replied, “Just looking for peace… and the children need education.”

Rahmatullah, a man introduced as the “camp representative,” said his duties included helping people with the Ministry of Immigration red tape and being a liaison to the various aid agencies serving the camp. A year ago he had moved his family from Helmand Province , where most of the camp's residents originated.

It took him only moments to determine what he would like to tell the world: “For the UN please, to stop the bombing and please help. This is not a place for life. We need more help and support from people in the U.S. and the UN.”

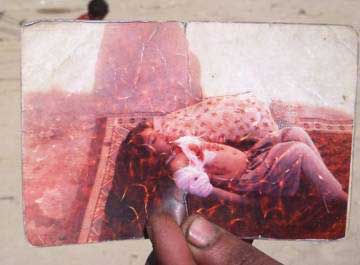

Growing suddenly more irate, the camp rep asked, “Where is your humanity? What is human rights in Afghanistan ?” Pointing to a man standing on the edge of a small knot of people, holding a few dusty, cracked photos, Rahmatullah demanded, “Is that picture human rights?”

A slight man of 30 years came forward and introduced himself as Faiz Mohammed, also from Helmand . His face did not bear a smile. In his hand he held a well-worn image of a girl, perhaps eight years old, lying in repose on a piece of carpet, with what appeared to be several wounds in her bloodied chest and upper abdomen.

Faiz Mohammed's daughter photo: Mike Ferner

“That is his daughter,” several of the men said at once. “And the girl in the other picture was her friend,” added another.

When asked what happened to them, Faiz Mohammed looked slightly quizzical and said, “The bombing.”

Dr. Ahmadzai interjected that Mohammed, like many others in the camp, suffered from rheumatism and general body pain due to the living conditions. “There is a lot of sickness here,” the doctor said. “Faiz Mohammed has a daughter suffering with pneumonia and a chest infection; his wife the same. Their wood ration is not enough. Not enough. A large family needs at least 15 kilos per day,” he said, pointing to a nearby “house” consisting of one 12x18 room, covered with tarps. “Sixteen people live in that house.”

Rahmatulla rejoined the conversation to make an announcement, confirmed later that day by news service reports, that the Afghan government and the Taliban had agreed to a temporary ceasefire in Helmand . “When fighting stops, that day I return to my home. We are people of one country,” he added with a mixture of pride and indignity. “Taliban are from Afghanistan . We are from Afghanistan . Government forces are from Afghanistan .”

As the camp visit drew to a close, I asked Rahmatullah what kind of work he did in Helmund. “Gardener,” he replied, hesitating a moment. Then, with a quiet smile he added, “Poppies.”

Ferner is author of “ Inside the Red Zone: A Veteran For Peace Reports from Iraq .” He spent two weeks in Afghanistan covering a delegation from Voices for Creative Nonviolence.

Comments are not moderated. Please be responsible and civil in your postings and stay within the topic discussed in the article too. If you find inappropriate comments, just Flag (Report) them and they will move into moderation que.