State Sponsored Crimes Against Adivasis In Assam

By Gladson Dungdung

14 March, 2011

Countercurrents.org

Burnt kid with her mother who died later

Introduction:

The Adivasis of Assam, whose ancestors had settled down in the land ‘around 150 years ago’[1] after they were forcefully brought from the states of Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhatisgarh, West Bengal and Orissa, have been facing state sponsored crimes since independence of India. They had been enjoying their rights and privileges before there were states called ‘India’ or ‘Assam’.

State sponsored crimes against the Adivasis began with the enforcement of the Indian constitution, which denied them their status as “Scheduled Tribe” though they had been enjoying the same right during British rule. Thus, their identity was either confined to the tea-leaf, which they plucked, or as outsider (migrant) labourers. Consequently, inhuman treatment was perpetrated on them by the state as well as non-state actors. The ethnic cleansing of 1996-98, Beltola incident of 2007 and force eviction of 2010 are classic examples of state sponsored crimes against Adivasis of Assam.

In fact, the state, whose prime responsibility is to protect and ensure the rights of everyone guaranteed by the Indian Constitution, has not only failed to meet its responsibilities - it has been discriminating against, exploiting and torturing the Adivasis of Assam. Ironically, the Forest Department has been carrying on eviction processes in Assam even after the enforcement of the Forest Rights Act 2006, which recognizes the rights of Adivasis over ‘the forests and forest lands’[2] from where they ensure their livelihood.

This paper examines the ground realities of state sponsored crimes against the Adivasis residing in Lungsung forest areas of Assam.

Adivasi woman with her kid in burnt house

1.Crime against the Adivasis:

Lungsung forest block of Kokrajhar district falls under the Bodoland Territorial Autonomous District (BTAD) of Assam, and is an abode of the Adivasis. They have been living in the vicinity ‘much earlier than 1965’[3]. However, the forest department claims that the Adivasis have encroached the forest, which is highly bio-diverse, and therefore they must be evicted from the vicinity. But the fact is that no such forest exists anymore in the vicinity where the Adivasis have been living for years. Despite that, the forest department launched an eviction move and had deployed the forest protection force for evicting the Adivasis located in the Lungsung forest areas.

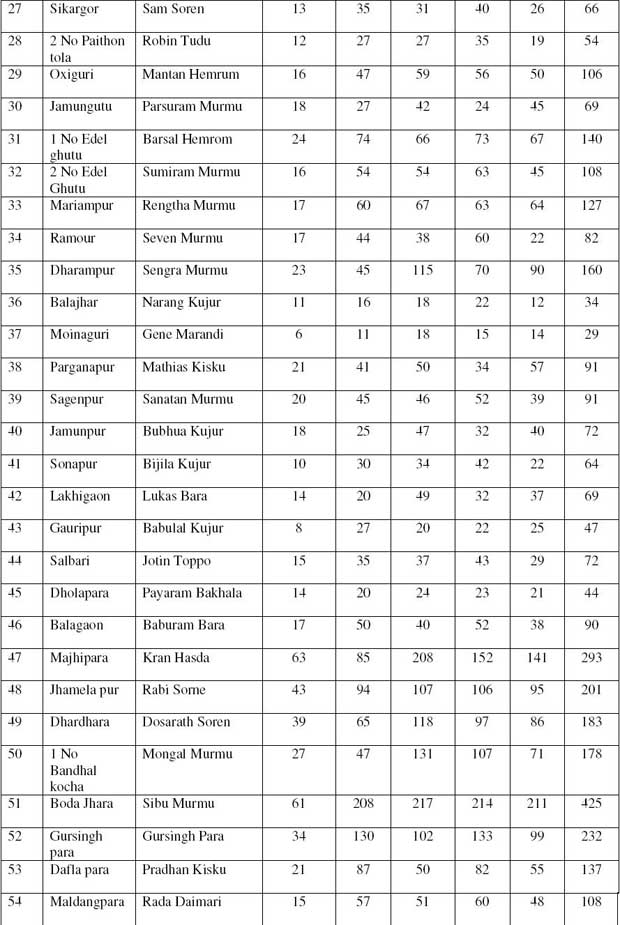

In this process, the forest protection force burnt 59 villages on October 30-31, 2010 and 8 villages were burnt again on November 22, 2010. Houses, clothes, and stored food grains were burnt down to ashes. In the move not a single house was spared. Consequently, 7013 Adivasis including 3869 adults and 3144 minors belonging to 1267 families were affected and out of them 3330 are males and 3683 are females (see Annexure-I). 2 year-old boy Mangal Hembrom died after struggling between life and death for more than 2 months as he was half burnt during the eviction process. 40 people who were leading the protests against the eviction were arrested, and later 7 of them (students) were released and the remaining 33 men were sent to Kokrajhar jail[4]. However, after intervention they were also released.

State sponsored crimes against the Adivasis of Assam had begun in ‘1950 by denying them the status of Scheduled Tribe (ST) in the Constitution of India’[5]. However, crimes were meted out to the Adivasis on a large scale since ‘1996 in forms of ethnic cleansing, where 10,000 Adivasis had been killed, thousands of them were injured and more than 200,000 were made homeless and compelled to live in the relief camps for more than 15 years’[6].

Similarly, on November 24, 2007, about ‘5000 Adivasis comprising of men, women and children were attacked in Beltola of Guwahati while they were attending a peaceful procession in demand of Schedule Tribe ‘status’[7]. They were attacked by the local people of Beltola including shopkeepers. Consequently ‘300 Adivasis were brutally wounded, hit by bamboos, iron rods and bricks. More than one dead, women were raped and a teenage girl Laxmi Oraon was stripped, chased and kicked’[8]. ‘The police either remained mute spectators or joined the crowd in brutality’[9]. However, instead of protecting the Adivasis, the government justified the brutalities and laid the blame on the Adivasi organizations.

It has also been intensifying crimes against them by carrying on eviction moves. According to the Executive Member of the Bodo Territorial Council, Santoshius Kujur, “The forest department will continue the eviction process once the Assembly Election is over in the month of April 2011”[10]. If this is true, there would be a gross violation of human rights committed by the government.

Rehabilitated house at lungsung

2.Pathetic conditions of Relief and Rehabilitation:

The victims of Lungsung incident are living in appalling conditions. The government has not provided them anything in the name of relief and rehabilitation. After the incident, the Agriculture Minister, Mrs. Protima Rani Brahma, visited the Lungsung forest areas and promised the victims that relief material would be provided. But the promised has remained unfulfilled.

Ironically, the government put a condition to the victims that if they were ready to desert their villages, they would be given the relief materials. However, the government does not promise them their rehabilitation even if they desert the vicinity. The question is - do they have right to food, clothing and shelter?

Meanwhile, some relief and rehabilitation work has been done by the NGOs, civil society and local community based organizations. The victims have been given eatables, utensils, clothes, medicines and tarpaulins but those are not enough.

Presently, the most of the victim families are bound to live either under the open sky or tarpaulin covered small huts, which can be again burnt by the forest protection forces during their eviction move. The unseasonal rain also adds salt to their wounds. The state does not bother to provide relief and rehabilitation to the victims. Similar kind of treatment was given to the victims of the 1996-98 ethnic cleansings too. They are still living in relief camps. They were not rehabilitated in their original villages properly. Their lands had been captured by the Bodos and not yet returned to them. In fact the government is not interested in addressing the issues of Adivasis at all.

3.Denial of Identity, Rights and Justice to Adivasis:

Historically, the Adivasis were brought to the state of Assam in three different circumstances. Firstly, the ‘Adivasis in general and Santals in particulars were brought to Assam for their resettlement after the Santal Revolt of 1855’[11].They were settled down especially in the ‘western part, now in the north-west of Kokrajhar district. This settlement is recorded as in the year 1881’[12]. Secondly, in ‘1880 the tea industry grew very fast, numbers of tea gardens were started. As a result, there was scarcity of labourers in Assam therefore the planters appointed agents and sent them to different places for recruitment of labourers’[13]. Thus, the Adivasis were ‘coerced, kidnapped and incited to come to Assam, live and work under appalling conditions’[14]. Thirdly, large scale land alienation for the development projects also pushed the Adivasis into Assam in search of livelihood, as there were many job opportunities in the tea gardens of Assam. Thus the Adivasis settled down in the state of Assam. Over a period of time, they also cleared the bushes and made cultivable land.

However, these ‘Adivasis were enjoying the Scheduled Tribe (ST) status during the British rules but when the Indian constitution was enacted, they were de-scheduled and considered as outsiders as then the Chief Minister of Assam opposed the scheduling of the Adivasis of Assam’[15]. Whereas, the same ethnic groups enjoy the status of Scheduled Tribe (ST), rights and privileges in their parental states i.e. Jharkhand, Chhatisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Bengal and Orissa, they are denied the same in the state of Assam. The government merely recognizes them as either tea or ex-tea tribe and the people of Assam called them coolies, Bengali or labourers in a derogatory tone. This is a classic example of discrimination against Adivasis by the government.

The Adivasis are discriminated against at every level, which is, of course, a crime. For example, in ‘1974 the government evicted the people but after strong people’s resistance the government had promised them to give land entitlements’[16]. At that time, Samar Brahma was the forest minister and as per his promise he started the process of land allocation in phased manner. However, he gave land to the ‘Bodos and some other communities. With his expulsion the process of land allocation also stopped’[17]. Thus, the Adivasis were betrayed. Similarly, according to the Forest Rights Act 2006, the Adivasis are entitled to claim their rights on the forest land which they posses before December 13, 2005. However, the Adivasis of Assam are denied their rights under the FRA as well. In fact, the ‘Adivasis have been living in Lungsung Forest areas much earlier than 1965’[18] but they were not given rights and entitlement on the forest lands which they have been cultivating for decades.

Burnt school at lungsung

4.Right to Education is denied:

The right to education is a fundamental right of every child. Therefore, the state is obliged to provide ‘free and compulsory education to the all children between the ages of 6 to 14 years’[19]. However, the government has been denying these rights to the Adivasi children of Assam, and especially the children living in the Lungsung Forest areas. The forest department has burnt down 10 schools, including 8 primary schools run under the Sarba Siksha Abhiyan (SSA) Mission and 2 private schools, during the eviction move, where the children were getting education and mid-day-meal as well. As a result, the children are being deprived of their right to education. Presently, a few schools have resumed classes under the open sky.

There are also practices of discrimination prevailing in schools, especially in the areas of tea estates. The schools are named as ‘Labourers’ school. For example, the name of a primary school situated at Senglijan is written on the sign board as “Senglijan Bonua Prathmik Vidhyalay (Senglijan Labour Primary School).

There is high dropout of children in class 8th and the reason behind this is that the parents can’t afford to send their children to school due to lack of money and awareness as well. Secondly, the quality of education is very poor, and doesn’t help them in getting jobs. It’s very difficult to get a graduate in many villages with quality education. If one sees the literacy rate of Adivasis, it is ‘merely 27.12 percent whereas the total literacy rate of Assam is 64.28 percent’[20]. Indeed, there is a clear division in the schooling system of Assam. The poor children go to the government or tea estate runs schools and there are public schools for elite children. Consequently, the inequality is growing day by day. However, the state seems to be reluctant in bridging the gap.

5.Livelihood Crisis:

The Adivasis of Assam have very limited livelihood options. A majority of them rely on the tea industry and the rest of them secure livelihood from farming. However, the wage of tea labourers is very low. They are paid ‘merely Rs.66 per day’[21] which is even lower than minimum wage of Assam which is Rs.100 for unskilled, Rs.110 for semi-skilled and Rs.120 for skilled labourer. The victims of Lungsung forest are even facing more livelihood crisis as their food grains were burnt and harvests were destroyed during the eviction move.

Similarly, the ‘Adivasis’ lands were captured by the Bodos during the ethnic cleansing in 1996-98 and they didn’t get it back’[22], which put them in livelihood crisis. Consequently, the Adivasis started migrating to the metro cities and other states in search of livelihood. The youth who migrate to the metro cities like Delhi and Mumbai, work as domestic servants and labourers. There are also cases of trafficking of huge numbers of women and children.

6.Destruction of tradition, Custom, Culture, Religion and Self Governance:

The Adivasis are known for ‘their unique tradition, custom, culture, religion and self governance’ [23]. However, they are bound to be alienated from their tradition, custom, culture, religion and self governance system. For example, the Mundas have lost their traditional self governance system and been ruled under the system of tea estates and religions, whereas the Santals, are still governed by their traditional self governance system. Most of the Adivasis have adopted other religions, though in practice they still observe Adivasi festivals like Karma, Sarhul, Baha Parab, etc. Most of the Adivasis speak in their mother tongues, perform their traditional folk dances and live in community, which is the strength of the Adivasi way of life. Their food habits almost remain the same.

Conclusion:

Indeed, the history of Assam suggests that the ‘government was the problem not the solution’[24] for the Adivasis of Assam. State sponsored crimes against the Adivasis must come to an end. The Indian State has promised to right the historic wrongs through the Forest Rights Act 2006, and therefore the victims of Lungsung forest must be given relief and rehabilitation package along with entitlement to the land they have been cultivating for years. The forest villages should be converted into revenue villages and basic facilities should be made available including drinking water, sanitation, health facilities, road, electricity, etc. The Assam government seems to be either a mute spectator or supporter of the perpetrators. Consequently, the perpetrators roam freely after committing heinous crime against the Adivasis. They must be brought to justice. The Adivasis of Assam should be recognized as Scheduled Tribe (ST) and included in the constitution of India and provided preventive, protective and promotive measures without any discrimination.

In fact, a law should be enforced to end discrimination against the Adivasis in Assam, where they are treated as outsiders and called by derogatory names i.e. coolie-Bangali, etc. though they have been living in the vicinity for more than 150 years and many of them are first settlers of the land. The minimum wages in tea gardens should be increased from Rs. 66 to 200 for unskilled and Rs. 300 for the skilled labourers. The living conditions of Adivasis living in the tea estate are very poor, therefore they should be provided basic facilities i.e. drinking water, health facilities, sanitation, etc. For ensuring the right to education of the children, there is a need to provide quality education to the children. Therefore, primary and secondary schools should be started in the Lungsung forest areas, where schools were burnt down to ashes. An attempt should be made to bridge the gap between the public and private schooling system without discrimination. There are more than 7,000,000 Adivasis’[25] living in Assam who are not recognized as Scheduled Tribe precisely because of political reasons. The state must protect and ensure the rights of the Adivasis of Assam.

Annexure I: Data of the affected villagers in Lungsung (Assam)

Notes:

[1] A Report on atrocities on Adivasis of Assam entitled as “Assam’s Adivasis” published (2008) by PAJHRA.

[2] http://tribal.nic.in/writereaddata/mainlinkFile/File1033.pdf

[3] N.A. 2011. ‘Assam Adivasis Cry for Justice’ jointly published by PAJHRA, HUL, PAD, DBSS and NBS.

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] N.A. 2007. Beltola Violence and its Political dimension. Guwahati: The Assam tribune. December 1.

[8] Ibid

[9] N.A. 2011. ‘Assam Adivasis Cry for Justice’ jointly published by PAJHRA, HUL, PAD, DBSS and NBS.

[10] A statement given by Mr. Santoshius Kujur an Executive Member of the Bodo Territorial Council.

[11] Chhetri, Harka Bahadur. 2005. Adivasis and the Culture of Assam. Kolkata: Anshah Publishing House. p 78

[12] Chhetri, Harka Bahadur. 2005. Adivasis and the Culture of Assam. Kolkata: Anshah Publishing House. p 48

[13] Gokhale, Nitin A. 1998. The Hot Brew: The Assam Tea Industry’s most turbulent decade. Guwahati:SP. p 6

[14] Ibid

[15] N.A. 2011. ‘Assam Adivasis Cry for Justice’ jointly published by PAJHRA, HUL, PAD, DBSS and NBS.

[16] Ibid

[17] Ibid

[18] Ibid

[19] Children’s Right to Education Act 2009.

[20] Ekka, Stephan. 2011. Economic Status of Adivasis of Assam.

[21] Pay Slip provided by the Tea Garden Labourer “Hira”.

[22] N.A. 2011. ‘Assam Adivasis Cry for Justice’ jointly published by PAJHRA, HUL, PAD, DBSS and NBS.

[23] Dungdung, Gladson. 2003. Sowing hatred in Adivasis’ land. New Delhi: Counter Currents.

[24] Tully, Mark. 2003. India in Slow Motion. New Delhi: Penguin Books. p xiv.

[25] Chhetri, Harka Bahadur. 2005. Adivasis and the Culture of Assam. Kolkata: Anshah Publishing House. p 78

References:

N.A. 2011. ‘Assam Adivasis Cry for Justice’ jointly published by PAJHRA, HUL, PAD, DBSS and NBS.

N.A. 2008. ‘Assam’s Adivasis’ a report on atrocities on Adivasis published by PAJHRA.

Gokhale, Nitin A. 1998. The Hot Brew: The Assam Tea Industry’s most turbulent decade. Guwahati:SP.

Chhetri, Harka Bahadur. 2005. Adivasis and the Culture of Assam. Kolkata: Anshah Publishing House.

Hussain, M. 1993. The Assam Movement: class, ideology and identity. Delhi:Manak Publications.

Guha, Amalendu. 2006. Planter Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle and Electoral Politics in Assam 1826-1947 Guwahati: Eastern Book Corporation.

N.A. 2007. Beltola Violence and its Political dimension. Guwahati: The Assam tribune. December 1. Gogoi appeases tea labour with slew of welfare measures, Press Trust of India, January 29, 2011

The Plantation Labour Act, 1951, Govt. of India.

Directorate for Welfare of Tea and Ex-Tea Garden Tribes, Govt of Assam

Gladson Dungdung is a Human Rights Activist and Writer based in Ranchi, in Jharkhand.

Comments are not moderated. Please be responsible and civil in your postings and stay within the topic discussed in the article too. If you find inappropriate comments, just Flag (Report) them and they will move into moderation que.