Rohith Vemula Is Not A Depression Story Mr. Manu Joseph!

By Shubhda Chaudhary

28 January, 2016

Countercurrents.org

“Poverty then is a factor, not a cause. Farmer suicide is a depression story, not an economics story. Tibetan monks who immolate themselves in protest against China are a depression story, not a political story. Suicide bombers are a depression story, not a radical-Islam story. Rohith Vemula, from all evidence in plain sight, is a depression story, not a Dalit story,” says Manu Joseph, the noted Indian journalist.

With an egregious statement like this, he revokes the same obnoxious contempt caused by historical masterpieces like ‘The End of History and the Last Man’ is a 1992 book by Francis Fukuyama or Samuel Huntington in ‘The Clash of Civilizations’, which academicians are still trying to refute. Joseph becomes the typical ‘organic intellectual’ described by Antonio Gramsci who speaks for the interests of a specific class, seeking to win consent to counter-hegemonic ideas and ambitions. Foucault rightly states that ‘a theorising intellectual . . . is no longer . . . a representing or representative consciousness. The intellectual’s role is no longer to place himself “somewhat ahead and to the side” in order to express the stifled truth of the collectivity.”

And Manu Joseph, unfortunately has failed, miserably, in being the right intellectual that India wants.

To start with, what is a ‘Dalit story’?

Isn’t it quite iniquitous to reduce the worth of a human, into a story, a narrative which is not indelible, just a casual occurrence, incapable of empowerment or emancipation? It’s like re-creating ‘The Other’ in terms of political dialectics, which can be sneered, tormented or berated without understanding the context of it?

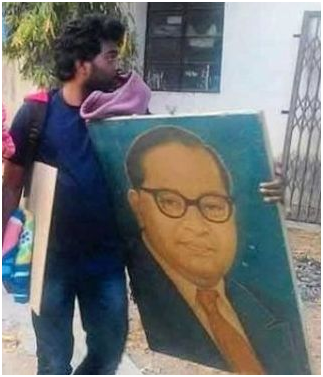

On December 18, Vemula had written a letter, by hand, to the vice-chancellor, stating, “Please serve 10 mg of Sodium Azide to all Dalit students at the time of admission. With direction to use when they feel like reading Ambedkar” and “Supply a nice rope to the rooms of all Dalit students.” Can’t we understand the context of it?

Joseph writes that ‘people tend to give an inordinate importance to the suicide note.’ Well, if it was not the suicide note, how would we know about the malpractices being carried out against Dalit students in Hyderabad University? How would have we known the prejudices and the influence of extraneous forces, apart from the utter ineptitude of the administration.

He even asks ‘But, as unpleasant as this question might be, did Vemula face such an extraordinary atrocity or tragedy? Perhaps, for Manu Joseph, the fact that Rohith along with four other comrades were expelled from the struggle, were surviving in the make-shift tent in the campus, just because of alleged assault on one Nandanam Susheel Kumar, the president of the HCU unit of the ABVP, which was never established. All the official inquiries, doctor’s testimony and the witnesses confirmed that it did not take place. So, what happened to him, was it justice? Or in his own words, ‘what is an extraordinary tragedy’ anyway?

Or is it justice to what happens with thousands of farmers who commit suicide, especially in Vidarbha in Maharashtra, every year? Trying to dispel their agony behind the case of depression or alcoholism, the government has anyway been trying to render them invisible. No one talks about the land grab, the corruption of allocation of government funds, the politics behind the very nomenclature of who can be a ‘legitimate farmer’ or why they are unable to repay their loans? No one talks about thousands of widows who are left behind, incapable of any government support after her husband suicides, just because, he might, in the government’s eye, ‘be a farmer’ or was ‘suffering from depression’. There are millions of stories like these, which are never uttered or believed because it’s easier to dispose them. Quite erroneously he states that ‘In a country where most people can be termed ‘farmers’, it is not anomalous that most people who kill themselves would be ‘farmers’’. Well, perhaps he does not know that after the farmer’s suicide, the family needs to fill up a 40 page questionnaire that question his identity and even if, on one single point, there is a loophole, the government denies money to the family, irrespective of how meager the amount might be. Leave the suicide, does Joseph understand the tribulation and agony that a family needs to undergo in order to establish that the deceased was a farmer?

Manu Joseph also compares the case of Rohith with that of Deepika Padukone who recently openly accepted that she was suffering from depression. Comparisons like these call for an utter laugh. On one hand, you have a celebrity, having all the facilities, paparazzi and limelight, who has control over her life and her decisions, who above all is not a ‘victim’. On the other hand, you have Rohith, who was a Dalit activist, who in his entire life had weighed the burden of his identity, who did not have control over how his identity is perceived, who was an outcast. How can an aberrant comparison like this even have an iota of intellectual thought?

Meanwhile, Manu Joseph comes from a state (Kerala) that has the highest suicide rates in India. Also, he should not reduce depression and suicides to only Dalits. It’s just a tremendous attempt for ‘Dalitisation of politics’ because it is nothing beyond it. The notion itself tries to manufacture consent that suicides take place within Dalits, as if the upper castes do not commit suicides. Don’t they?

Clearly dogmatic about his view, Joseph further reiterates that ‘the fact that thousands like him who face far worse do not end their lives, points to one dominant influence. The nature of clinical depression is that it is in constant search for reasons to bring the pain to a close.’ One must ask him, how many so-called ‘Dalit stories’ has he heard which were emancipated? Officially, does the state even reveal the deaths of Dalits or farmers or suicide bombers’, be it in context or numbers? It’s the misfortune of today’s era, especially in Indian context, that to cause a protest, an agitation, or for that matter, to be taken seriously, someone needs to die. Death, here rewards, only posthumously.

It's sheer shame that Manu Joseph could have been so insensitive when scholars like P. Sainath, Meena Kandaswamy, Subhash Gatade, Ravichandran Bathran are voicing their support, lamenting at the death of a bright student intellectual who loved ‘science and stars’, idolized Carl Sagan and thought minutely about his own existence. It reveals how deep-rooted casteism is indoctrinated within our mental faculties that even the idea of ‘the other’ can agonize it to the level that it can create its own fabricated ‘Dalit Story’.

Along with dealing with Rohith’s death, Joseph also casually talks about clinical depression as if it’s just another disease, reducing its deep-rooted scars and pain that it causes to a human soul. He certainly does not understand what clinical depression is, a fact that is quite evident from his superficial reading of it, perhaps accidental or occasional. ‘Research worldwide, including in India, suggests that at least one in five women and one in 10 men suffers from major depressive disorder at some time in their lifetime,’ states Dr Shamsah Sonawalla, consultant psychiatrist. There are thousands of Indian citizens, in fact 1 in 10 Indians, who navigate through jagged decades of health and work, tormented by troubled moods and disturbed brains, alternating between full-blown agitation and wakeful lucidity, causing heartbreak to their loved ones and challenges to their doctors. Does the nation care? Perhaps, not!

So then, Manu Joseph, if Rohith Vemula, from all evidence in plain sight, is a depression story, not a Dalit story, we would be truly unfortunate to witness when a ‘Dalit story’ in your vocabulary does take place. P.Sainath has rightly ‘French writer Victor Hugo wrote that there is nothing on earth that can stand in the way of an idea that has come. In India in 2016, I think that time has come. And the idea, is justice: social, economic, cultural, gender and for Rohith and a billion other Rohiths.’

So, Mr. Joseph, this is a desperate attempt to pawn your idea and gain attention. Nothing else. Nothing can be so disappointing than your disparaging remarks to the unfortunate suicide of Rohith Vemula. My argument is, instead of trying to fit the episode in your own fabricated theory, please come with a solution. Nothing else really matters because India would soon forget Rohith, as it did with Nirbhaya. The chaos, views, rebuttals will suddenly end. If we need to more forward and make a concrete change, we don’t need your recycled verbatim but a solution.

Shubhda Chaudhary is a PhD scholar in International Relations at JNU. She is also working with think tanks in Abu Dhabi and South Africa. Email Id : shubhda. [email protected]