Che, My Father: Daughter Recalls The Revolutionary

By Countercurrents.org

09 September, 2012

Countercurrents.org

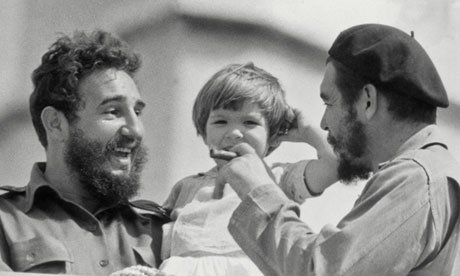

Aleida Guevara with her father and Fidel Castro in 1963. Photograph: Getty Images

Che, a symbol of revolution around the world, was murdered 45 years ago. Aleida, Che’s daughter tells about the revolutionary.

Tracy McVeigh sketched Che and Aleida in guardian.co.uk on September 8, 2012. Following are excerpts from Tracy’s article:

She has the eyes of her father, a gaze that became an emblem for the 20th century. She also has his deep sense of social injustice, but Dr Aleida Guevara has always had to share her "papi" with the world.

While she doesn't mind the posters, the flags, the postcards, graffiti paintings and T-shirts, Dr Guevara and her family are trying to clamp down on "disrespectful" uses of her father's famous photo, taken by Alberto Korda in 1960. Not easy when it is the most reproduced image in the world.

"It's not so easy, we do not want to control the image or make money from it, but it is hard when it's exploited," Dr Guevara smiles. "Sometimes people know what he stands for, sometimes not. Mostly I think it is used well, as a symbol for resistance, against repression."

Next month marks the 45th anniversary of the killing of Ernesto "Che" Guevara, the guerrilla who helped lead the Cuban revolution and became an icon of rebellion. This year is also the 50th anniversary of the US "blockade", the ongoing commercial, trade and travel embargo which has stifled Cuba's economy. The cold war era-style standoff still sees America spend millions beaming propaganda radio and TV stations into Cuba. Cubans remain the only immigrants the US encourages in with automatic citizenship.

Dr Guevara is in the UK for another anniversary, the 14th year since the Miami Five – spies entrusted with infiltrating anti-Castro terrorist groups operating from Florida – were jailed by the US. The 51-year-old Havana paedriatician will lead a vigil in London outside the US embassy on Tuesday evening. "I'm not political," she insists, "but I care about injustice."

Aleida was seven when Che was killed in a remote Bolivian hamlet by a group of Bolivian soldiers and CIA operatives. With only shadowy memories of her father, she has got to know him through his diaries and the reminiscences of others, including the man she calls "Uncle" – Fidel Castro.

"Fidel has told me many beautiful stories about my father, but I cannot ask him too much, he still gets very emotional at the thought of Che. For example, my father had terrible handwriting, so my mother was asked to transcribe his diaries. When Raúl Castro came to our house to collect the manuscript, my mother knew that Raúl and Fidel also kept diaries, so she said 'if there are accounts in the diaries that differ then you must go with Che's, because he is not here to defend himself'. Raúl got very angry and said 'No, while Fidel and I are alive, Che is alive. He is always with us.' They were crying then.

"If Che hadn't died in Bolivia, he would have died in Argentina trying to change things there," she says. "Maybe it would be a different continent today. My mother always says that if my father had lived we would all have been better human beings."

[…]

"We had great hopes, but we are disappointed in Obama, maybe things have even got worse for us," Dr Guevara says.

Revolution, she believes, simmers on in Latin America, where the gulf between rich and poor is escalating and she blames, as Che did, creeping American-led industrialisation. "This economic crisis is even more dangerous than any before for Latin America. It's not only about oil now, the US want water too. Brazil is destroying its rainforest to mine out iron, Mexico is a dumping ground for unwanted waste. This time the land is being destroyed as well."

Critics of Che claim the photogenic young man in battle fatigues who wrote poetry overshadows the brutality of his revolution. Guevara showed no qualms about killing. "It was a revolution," says his daughter. "Of course, I would rather there was no bloodshed but that is the nature of revolution. In a true revolution you have to get what you want by force. An enemy who doesn't want to give you what you want? Maybe you have to take it. My father knew the risk he took with his own life.

"I was angry, of course, growing up without a dad, but my mother always says, love your father for who he was, a man who had to do what he did. My father died defending his ideals. Up to the last minute he was true to what he believed in. This is what I admire."

But she says she would like to have been able to argue with him. "When I was six he sent me a letter. In it he said I should be good and help my mother with household chores. I was angry because my brother's letter said 'I will take you to the moon' and my other brother's read 'We will go and fight imperialism together'. I was annoyed – I wanted to go to the moon, why couldn't I fight imperialism?"

Dr Guevara is the eldest of Che's four children with his second wife, Aleida. "We didn't have privileges growing up as Che's children. My colleagues didn't know who I was until I first talked on Cuban TV in 1996. But it's important not to keep silent, because there is injustice being wrought."

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/sep/08/che-guevara-daughter-aleida

On another occasion, Aleida talked about having to share her 'Papi' with the world – and her dislike of the commercialisation of his image.

Libby Brooks wrote on the issue in The Guardian on July 22, 2009. Libby’s report was headlined “Che Guevara's daughter recalls her revolutionary father”. Following are excerpts from the news-story:

Aleida Guevara was four and a half when her father left Cuba. […] She saw him only once again, before his execution by the CIA-backed Bolivian government two years later.

Castro granted the visit on condition that it was clandestine. Guevara, concerned that the children's chatter about "Papi's" re-appearance might endanger his family, arrived back in Havana heavily disguised. He was introduced at supper as a friend of their father.

"After supper, I fell and hit my head," Aleida recalls. "He was a doctor, of course, so he treated me, but then he picked me up and cuddled me. I remember a feeling of complete protection and tenderness. Later I said to my mother, 'I believe that this man is in love with me.'" She laughs at her childish grandiloquence. "I was only five. But I knew that this man loved me in a very special way. I didn't know that it was my father, though, and he couldn't tell me."

Aleida, […] a committed Marxist and medical doctor, just as her father was, the thick, bobbed hair, broad features and deep-set eyes are immediately reminiscent of the face without which no student common room is complete. "When I see [his face] commercialised, or used for advertising," Aleida intones sharply, "I don't like it."

[…] She has inherited her father's charisma and mellifluous exposition, but exercises it more intimately. Talking about politics, she employs the language of emotion rather than that of arid ideology.

Guevara's legacy, she tells me, is his life. "My father knew how to love, and that was the most beautiful feature of him – his capacity to love." She touches my arm. "To be a proper revolutionary, you have to be a romantic. His capacity to give himself to the cause of others was at the centre of his beliefs – if we could only follow his example, the world would be a much more beautiful place."

So why is it that Cuba, an island that throughout its history has been coveted, bullied and demonised by mightier nations, continues to draw worldwide fascination? Her answer may seem simplistic, but it is instant: "Because of Cuban men and women. We're a cultured, educated people – and possibly one of the only ones in the world to say no to the United States."

That "no", of course – regardless of whether it was dictated by an iron regime, as some would argue, or articulated by the populace – has manifested devastating consequences. The vicious embargo imposed on Cuba by the US the year after its revolution continues to suffocate the country. And as a practising paediatrician, Aleida is all too familiar with the daily realities of the blockade.

"There was a case of a girl, six months old," she says. "She had a condition where the digestive system would flood with blood, and the only treatment available is patented by the US. Cuba had the money to pay, but not one company in the whole global medicine market would offer it." She presses together her thumb and forefinger in a gesture of frustration. "Any pharmacological distributor daring to deal with Cuba would be investigated by the FBI. The government can pull out investment or boycott their goods. We couldn't get the medicine and the baby was dying. The only sin of that girl was the fact that she was born in Cuba."

[…] "What Obama has done is to return to the policy that existed under the Clinton administration. There's nothing new here. He promised to close Guantánamo, but that hasn't been done. There is a lack of continuity between what he says and what he does. So far we haven't seen anything that would indicate a change of course.

"If the blockade was lifted, things would change immeasurably. The Cuban economy would flower. That's the missing link."

Coincidentally, in advance of Aleida's visit, the Cuba Solidarity Campaign has unearthed what are believed to be the earliest colour photographs of her father, taken by a British international brigade volunteer who travelled to the island in 1960, the summer before Aleida was born. The elderly woman unearthed her slides in a shoebox full of mementoes, never having realised the significance of the man she snapped on her colour camera. So how did Aleida feel when she first saw the photographs? "It was beautiful," she says. "The woman who took the photos actually worked in Cuba building a school. So even in the old days there were people giving their solidarity. That's the value of the photos to me."

Her father looks like he always did, she says; natural and with people surrounding him. "I'm very grateful to this woman for giving me a piece of him that I knew existed but had never seen. But what I am most grateful for is that she remains in solidarity with Cuba."

Her mother will be pleased to see them too, she adds. Aleida March was a member of Castro's guerrilla army when she met her future husband in the Cuban bush, and impressed him with her knowledge of the local terrain (Guevara was previously married to exiled Peruvian revolutionary Hilda Gadea). Now in her 70s, March has published a memoir about her life with Guevara, and how she raised their four children after his death. "You can buy it in any language you want except English," her daughter teases. "Do you read Turkish?"

The ideals of both parents inevitably influenced Aleida's own consciousness, but you can't impose ideals on children, she cautions. "You can only show by example."

It sounds far-fetched that a man intent on fomenting leftwing revolution in post-colonial Congo would find the time to make up animal stories for his faraway children, but Aleida says he did just that.

"My father didn't have the opportunity to enjoy our childhoods. But when he was away, which was most of the time, he would send us stories and drawings on postcards. My brother Camilo was told off at nursery school for using swearwords, and my mother confronted Che because he had a habit of swearing – as all Argentinians do," she notes archly. "He was in Africa and he wrote to Camilo telling him that he couldn't swear at school, or Pépé the Caiman [a reptilian character invented by Guevara] would bite off Che's leg." She grabs my calf. "So he had to stop swearing to protect his father."

Domestic as these reminiscences are, Che has, of course, never been solely Aleida's Papi or property. Alberto Korda's iconic portrait, taken at a funeral service in 1960 – jaw clenched, eyes to the horizon, unkempt locks under a red-star beret – has been reproduced on posters, T-shirts and advertising hoardings ever since. His image, if not his ideals, has entered the lexicons of adolescent rebellion and creative subversion. Last weekend, I spotted a teenager swinging a Che bag down Oxford Street and asked him why he'd bought it. Che was this cool guy who talked about revolution, he said. What revolution meant, he found harder to articulate.

"When you see a child carrying his image on a march and the child says to you, 'I want to be like Che and fight until final victory', then you feel elated," Aleida says. "But the most surprising thing is that this event happened in Portugal, not in Cuba."

But how does she feel about the use of his image in the El Commandante pub in Holloway, London, and the Che memorabilia crowding every proto-conscious market stall? She frowns. "I saw him used to advertise an optician's in Berlin. A fashion designer showed his underwear designs in New York reprinting his face." The thumb and forefinger connect once again. It all depends on the context. "But if a young person wears the T-shirt and starts to understand who this person was, then that's fine."

Aleida is similarly ambivalent about Hollywood's recent obsession with her father. Walter Salles's Motorcycle Diaries, which traced Guevara's early, transformative travels throughout Latin America, was a magnificent film, she enthuses, that showed a young person learning about poverty and refusing to turn his back on it. The more recent two-part biopic Che, starring Benicio Del Toro, was disappointing. She had expected a more complete presentation of the revolution.

The vocabulary of struggle, consciousness and sacrifice that Aleida uses may feel anachronistic to a British audience versed in the minor political narratives of personality conflict and fiddled expenses. But there is another story about Cuba, still to be told. As the west waits eagerly for further dispatches about Castro's failing health, for Aleida, his demise can only usher in a new beginning.

"The US propaganda machine has dedicated itself to telling everybody that the revolution depends on just one person. But there is an inner conviction among the Cuban people. So, when the time comes when Fidel isn't with us physically any more, they will find a way forward. And if they can't do that, they will disappear. Pablo Milanés said once it is preferable to sink in the sea than to betray the glory that once lived. And for us that rings true."

The Cuba Solidarity Campaign is an NGO that campaigns for an end to the US blockade of Cuba (cuba-solidarity.org.uk).

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jul/22/che-guevara-daughter-aleida?INTCMP=ILCNETTXT3487

Be a friend to mankind: Che

With the headline “Che, my father”, Angelique Chrisafis wrote in The Guardian on May 3, 2002:

As she talks about her father Aleida doodles love hearts in pen on a battered desk. She doesn't know she is doing it. Round and round goes the nib in the grip of this militant, communist paediatrician, daughter of a 20th-century legend.

[…] Aleida had only a handful of encounters with him during his snatched returns. Desperate to see his children, he hid behind strange outfits, false beards and false identities. He worried that his children would recognise him as "papi" and talk at nursery, giving away his whereabouts. They knew they liked this "very good friend of daddy's" but couldn't say why.

Aleida is in Britain to set the record straight on the bizarre world of "uncle Fidel", and "daddy Che". […] But Aleida, who was seen on podiums in the 1960s hanging on to his olive trouser legs, is here to prove the children of the revolution's commitment to the future.

[…] Cuba does not claim to be perfect she says, nor does it set out to be a model for anywhere else in the world. "We have economic problems, we are just sitting down and putting our heads together about how to improve things as best we can, to improve life for our people, given the international attitudes towards us and the pressures we face.

"Sometimes I wish propagandists from abroad would just leave us alone to get on with our lives. Fortunately, teenagers are very good at discerning the truth behind anti-Cuba propaganda. OK, they may not have the jeans they want, but they know there's more to life. We might not have the latest fashions, but we are all clothed."

[…]

It hurts her that on her first visit to UK, she must see his face - her face - staring out from its life sentence of consumerism, in stalls in Camden market, on beer bottles, ash trays, and punk-metal album covers, forever the symbol of the capitalism he hated. I tell her a friend of mine once drank in an Irish-Cuban bar in the Czech republic called O'Shea Guevara. She shakes her head. "I don't want people to use my father's face unthinkingly. I don't like to see him stitched on the backside of a pair of mass-produced jeans. But look at the people who wear Che T-shirts. They tend to be those who don't conform, who want more from society, who are wondering if they can be better human beings. That, I think, he would have liked."

[Cuban revolutionary Aleida March, Che’s wife, and Che] were happy, although he spent much time abroad. Che was travelling between Eastern Europe and China when Aleida was born, and was also away for the births of his younger children - Camilo, Celia, Ernesto - all now working in Cuba, two as lawyers and one as a vet specialising in dolphins.

"My father was true to the impression you have of him," Aleida says, touching my arm as I reminisce about posters in student halls of residence and how all the girls on my Latin American politics module fancied him. Surely she must find that odd.

"He was a special, magical human being, with a capacity to give himself completely to something, to a cause, to inspire. He gave himself completely to my mother, with a great thirst for love - a great lover. He was never afraid of succumbing to any cause or emotion," she smiles. Guevara had certain obsessions and values, she recalls. They were passed down in letters to his children "Don't mistreat books. That was a really strong belief. Be a friend to mankind, do not put up with injustice of any kind, anywhere, and be worthy of your country. Nothing more than that, but that was a lot."

In South America, Guevara was tracked by international powers. "In his letters from the jungle, he invented a character called Pepe the crocodile and would write to us about how grouchy the beast was," says Aleida. She was almost six when he turned up in various disguises. "I am a friend of your daddy's, a good friend," he told her, disguising his Argentinian accent, saying instead he was Spanish.

Aleida was filled with strange feelings towards the visitor that she couldn't explain. "I wanted to impress him. I didn't recognise him as my father but I had feelings for him. […]

"Later I said to my mother, 'You know that man? He loves me.' I didn't know why he loved me, and of course my mother couldn't explain, in case I told."

On his visits, Guevara gave his children sweets. When Aleida handed her whole packet straight to her baby brother, Guevara said: "You've made me so proud. That is such a noble act to sacrifice your sweets as the eldest child that I will give you another packet."

Aleida seemed proud and embarrassed as she tells the story. Has she tried to become her father?

"It's just coincidence that I am a doctor and my father was a doctor, too, that I have the same views. I developed them for myself as a teenager. By that time I'd stopped wanting to be him. I made my mind up for myself."

Before we part, she touches my arm. "Why do people here keep asking what will happen after Fidel? He is a very special person who has united us. It will hurt us deeply when he dies. But as a people, we have withstood a tremendous amount from abroad and from the US. There is no question that a people that strong have commitment to continue the cause."

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2002/may/03/cuba.angeliquechrisafis?INTCMP=ILCNETTXT3487

Che branding denounced

Rory Carroll, Latin America correspondent, wrote, headlined “Guevara children denounce Che branding”, in The Guardian on June 7, 2008:

The scraggly beard, the beret adorned with a star, the intense gaze: it is an instantly recognisable image which has been used to sell everything from booze to T-shirts to mugs to bikinis.

Che Guevara’s […] brand has turned into a worldwide marketing phenomenon. If you want to shift more products or give your corporate image a bit of edge, the Argentine revolutionary's face and name are there to be used, like commercial gold dust.

The fact that Guevara was a communist guerrilla and Marxist ideologue is an irony of little interest to his capitalist exploiters. It has, however, become a problem for his children.

Aleida [has] denounced the commercialisation of her father's image as an affront to his socialist ideals. "Something that bothers me now is the appropriation of the figure of Che that has been used to make enemies from different classes. It's embarrassing."

A man who fought and died trying to overthrow capitalism and material excess should not be used to sell British vodka, French fizzy drinks and Swiss mobile phones, among other travesties, she said. "We don't want money, we demand respect."

Aleida […] made the comments during an internet forum sponsored by Cuba's government ahead of what would have been her father's 80th birthday on June 14.

The complaint came amid a surge of renewed interest in Guevara. […]

Camilo Guevara, a son, who participated in the forum, said he welcomed the film [Che by Steven Soderbergh] as long as it was faithful to his father's memory.

Last month Buenos Aires unveiled a towering bronze statute of the young doctor […] radicalised by oppression and poverty in Latin America.

Guevara was a […] fervent critic of "material incentives" but in death he became transformed into an icon of daring and rebellion.

The famous image portrait was based on an image taken by the Cuban photographer Alberto Korda in Havana in 1960. It was pinned to his studio wall for seven years until the Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli mass produced it around the time of Guevara's death.

Korda willingly forfeited royalties but he sued a British advertising agency for using the photo to promote vodka.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/jun/07/cuba?INTCMP=ILCNETTXT3487

Comments are moderated