One-Third Of Turks Are Poor or Needy

By Countercurrents.org

09 June, 2013

Countercurrents.org

Nearly one-third of Turkish people, 23.6 million, are poor or needy and more than 6.3 million people from 2.1 million households are receiving social assistance. Citing the 2012 social assistance statistics released by the Family and Social Policies Ministry a news [1] of Hürriyet Daily News (HDN) reported.

However, poverty rates decreased in 2009 in compare to 2002 numbers, said the report. The ministry's data said: Hunger poverty decreased to 0.48 percent in 2009 from 1.35 percent in 2002. The report listed no one in hunger poverty in 2010 and 2011. Those living on under 1 dollar a day totaled 0.01 percent in 2005 and the report cited no one in this category since that year.

The country's population reached 75.6 million in 2012, according to data released by the Turkey 's statistical authority, TÜIK.

A bad time

Another HDN-report [2] said:

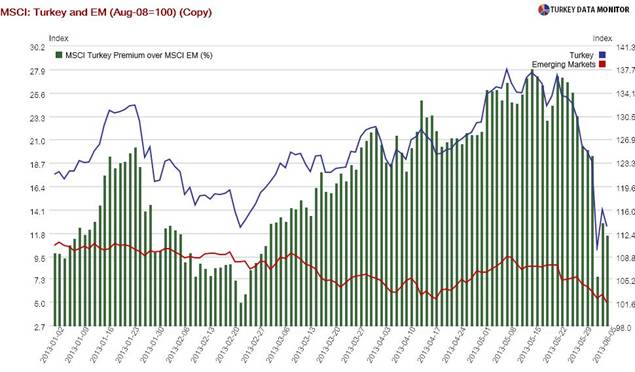

The demonstrations caught the Turkish economy at a bad time. There was almost a mini-crisis in emerging markets ( EMs ), which had already seen the first net outflows in almost a year in the week ending on May 29. There were actually sell-offs during the whole month.

In Turkey , there were $300 million of outflows last Friday, before the start of the police crackdown, and $1 billion for the whole week. Turkish assets are high-beta: they do better than other EMs in good times but underperform in bad times. Turkish equities have indeed doing much worse than peers since the third week of May.

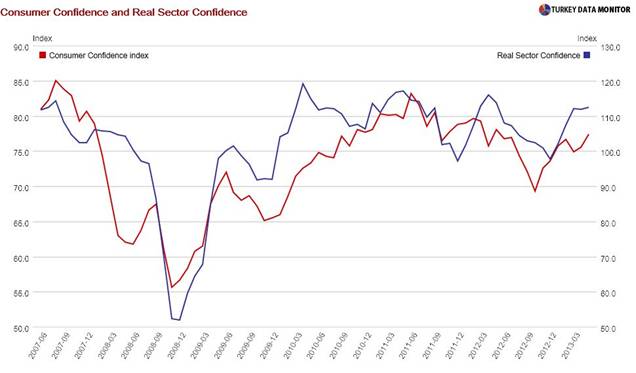

It is also important to note that the economy is on a very fragile recovery path, as the weak May Purchasing Managers Index confirmed. While the overall index fell slightly to 51.1 from 51.3, the exports component hit a six-month low. The pace of recovery is therefore likely to depend on domestic demand, and therefore on consumer and business confidence.

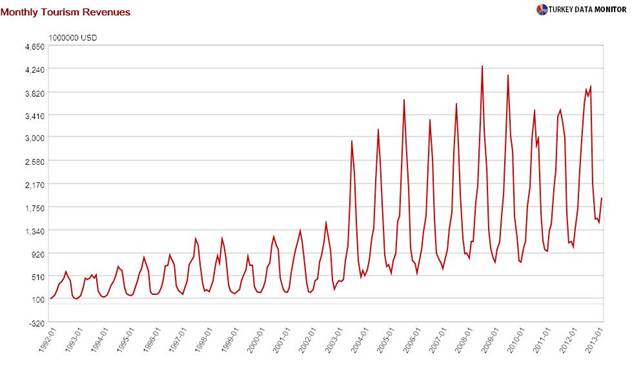

Turkey earns more than two-thirds of its tourism revenues in the five months: June - October. Tourism revenues are important because they somewhat alleviate the current account deficit, which is one of the country's main vulnerabilities.

So what fate awaits markets and the economy? Turkish assets were unsurprisingly hammered on Monday. They did somewhat stabilize afterwards, but the long-term fate of Turkish assets and the economy is in the hands of Erdogan. If he adopts a reconciliatory stance, the country will slowly normalize.

But if he does not step back form the hardline stance and demonstrations go on throughout the summer, the real economy could be affected through the confidence channel, tourism revenues could decline significantly, and there could be heavy capital outflows, depreciating the lira and undermining the balance sheets of the corporates with heavy open foreign currency positions. Erdogan cannot afford instability before an elections year, and so he would probably resort to pork-barrel spending, undermining the economy's fundamentals further.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) could be disrupted as well. Turkey 's external financing has been short-term of late, and some FDI would make the country sturdier against a sudden stop of capital flows.

If his advisers eventually put some sense into Erdogan, the next few months will be anything but rosy because political stability, which had been priced into Turkish assets, is not a given anymore. Turks did not rise against a mall; they were simply fed up with the authoritarianism taking the form of alcohol bans, police brutality and the like. And so even if things calm down, I would not be surprised to see similar protests the next time the government tries to enforce its will on the people.

Fault-lines in the economy

Another report by Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura, BBC Business reporter, [3] said:

Spooked by the anti-government protests across major cities in Turkey , thousands of foreign businessmen and women invited to attend a medical conference in Istanbul this month cancelled their trip at the last minute.

Eda Ozden, an employee at a travel agency that organizes events for Fortune 500 companies, said clients have called seeking advice on what to do about events booked in two years' time.

"That's very bad. The impact is wide - from hotels, bus and taxi companies, restaurants," she told.

"Tourism so far has only taken a hit in the short run. But... June being the highest season for tourists in Turkey , the industry is afraid. This has happened previously with 9/11, the 2003 Istanbul bombings and the 1999 earthquake. It took until 2005 for our companies to become profitable again." While the impact of the demonstrations on the economy appears to be limited to a part of the tourism industry for now, even a small bump can be magnified in a country where much of the economy hinges on the services sector.

It makes up 63% of the country's GDP.

Turkey is the sixth most popular destination in the world, having attracted 31 million tourists in 2011 and valuing the industry at $30bn.

"It doesn't help that there are photos [in the media] showing the smoke-filled lobby of the InterContinental," said Ms Ozden.

Turkish businesses are nervous, uncertain whether the protests are causing just a blip in an otherwise stellar economic performance or putting them on the cusp of a damaging decline.

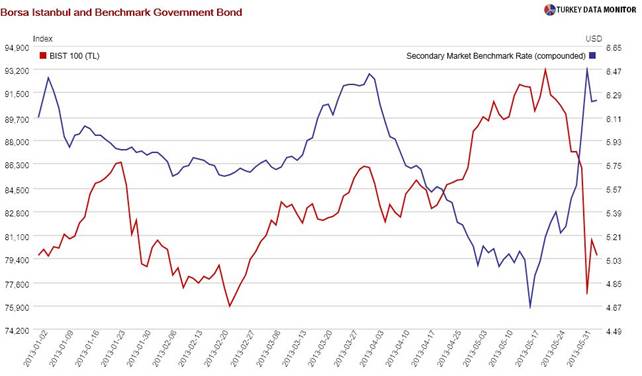

Jitters were particularly felt in Turkey 's stock market, which plunged by more than 10% on Monday - its sharpest drop in 10 years - as investors, many of them foreign, started to pull their money out of the country.

Stocks continued their descent on June 6, 2013 after prime minister Erdogan said he would go ahead and root up Gezi Park and replace it with a shopping mall - a plan that had originally sparked the unrest.

Turkey 's economic growth has skyrocketed since the early 2000s - around the same time Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP) assumed power - after implementing austerity measures advised by the IMF. The 1990s had been spent in gloomy stagnation.

'Hot money': Speculative investors

While a politically conservative party, the AKP championed a more liberal view of the economy, opening it up to global financial markets and privatizing state assets – moves that earned strong supporters in the business community.

In 2011, while most Western economies were feeling the effects of the financial crisis, Turkey 's growth rate was 8.5%, helped by reforms - for example, relaxing barriers for start-ups and companies, and removing travel visas for Russian citizens to boost tourism.

Growth declined sharply last year to 2.5% as the global economy stalled. Foreign companies were lured by the perceived political stability under Erdogan's decade-long rule: Microsoft, Coca-Cola, McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group and clinical research groups set up regional headquarters in Istanbul .

The US drugs company Pfizer last month announced it was moving its EU headquarters from Brussels to Istanbul .

It also helped that credit rating agencies upgraded their ratings on Turkey 's sovereign debt.

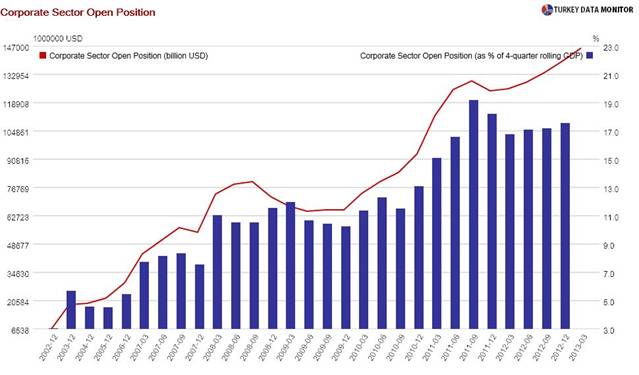

But much of the growth in the past decade has masked a fragility – a dependency on external debt, which, at a moment of crisis can leave a country dangerously exposed to market volatility and the whims of investors. Short-term investment from abroad has surged in recent years, while long-term investment has fallen.

High domestic interest rates attracted short-term foreign capital. That pushed up the value of the Turkish lira, making imports cheaper and sparking a boom in demand for foreign goods.

That was good for the growing Turkish middle-class. But the influx of short-term foreign money - known as hot money - meant that the prosperity relied on speculative investors from abroad.

Analysts say the country needs $200bn a year to finance its current account deficit and maturing foreign debt. Since the start of the year, 60% of this sum has been financed by this hot money. Another 20% came from banks borrowing abroad.

Net external debt stands at $413bn, or about 51% of GDP. Goldman Sachs analysts last month described Turkey as one of the most debt-laden economies "in the emerging-market universe".

"The influx of foreign capital and growth gave the perception of stability. Now that stability is under question, which puts the influx under question, and throws the 'economic miracle' in doubt," said Ergin Yildizoglu, a columnist for the Cumhuriyet newspaper.

'Nuclear economic winter'

"Foreign investment has played such a major role that if there is panic or concerns about the Turkish economy, then that would be devastating," said Tolga Esin, a tech entrepreneur and founding partner of Formondo, an e-commerce and mobile app platform,.

"I don't think that will happen at this point - unless or until things get worse."

But for another businessman in his 30s, who goes to work in the mornings and joins other protesters in the evenings, the short-term turbulence in markets or in some areas of the economy are a necessary sacrifice to bring about fundamental change in a government that has overstepped its authority.

"Until now, foreigners looked at Turkey through a lens that the AKP party wanted them to see" as a peaceful nation and an economic success story, he said, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was afraid of reprisals.

"Internally, we had doubts about how we were ruled. But now the world can see that the AKP is very powerful - and not nice," he added.

The direction of the protests - and the economy - will depend on the government's response.

Atilla Yesilada, a partner at GlobalSource, a research group, wrote in a blog post: "The AKP is at the threshold of the most delicate decision of its 11-year reign: How to handle the protests.

"This is not the Turkish Spring, but if the AKP presses the wrong button, it could become 'the nuclear winter of the economy'," he warned.

Source:

[2] “The economic consequences of #OccupyGezi”, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/the-economic-consequences-of-occupygezi.aspx?pageID=449&nID=48349&NewsCatID=430

[3] June 6, 2013, “ Turkey protests reveal fault-lines in economic success”, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-22778768

Comments are moderated