Burma’s Rohingya Bear Witness, In India

By Erika Berg

28 October, 2015

Countercurrents.org

The 196 works of narrative art in the powerful new book, "Forced to Flee: Visual Stories by Refugee Youth from Burma", bear witness to the memories, struggles and dreams of young people forced to flee violent conflict and persecution in the ethnically diverse nation of Burma, also known as Myanmar.

Among Burma’s 135-plus ethnic groups are the Rohingya; the largest concentration of Rohingya, about 800,000,live in northern Rakhine State. A Muslim ethnic minority who speak an Indo-Aryan language and practice Islam, many Rohingya descend from families who have lived in Burma for generations. Viewed by the government as “illegal Bengali” from neighboring Bangladesh, Rohingya are denied citizenship. Burma’s 1982 Citizenship Act rendered them officially stateless.

In June 2012, an outbreak of violent conflict between Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State ignited long-simmering tensions between the communities. State security forces were unable or unwilling to quell the violence. In some cases, they were actively complicit. A week later, President Thein Sein declared a state of emergency. The following month he told the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) that the only solution was to send the Rohingyas to UN-administered camps or to a third country. Within a year, 142,000 displaced people in Rakhine State, the vast majority Muslims, had sought refuge in camps that segregated Buddhists and Muslims. Meanwhile, anti-Muslim violence spread beyond Rakhine State, impacting Muslims with legal citizenship. Suddenly, Muslims nationwide lived in fear.

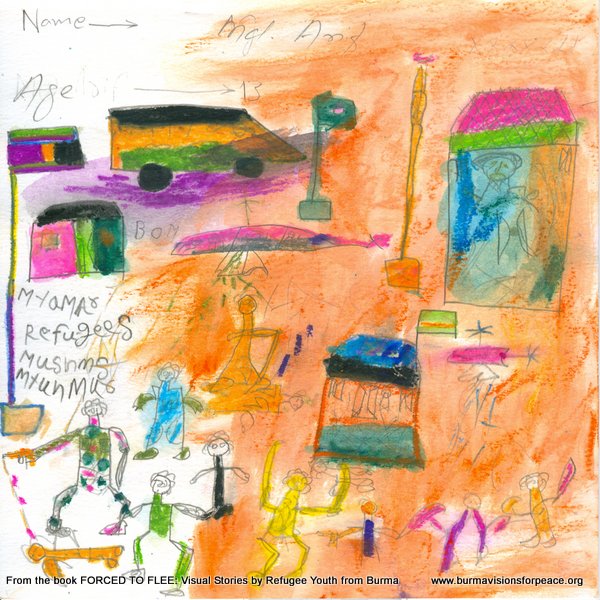

Today, Rohingya are unable to marry, travel outside their villages or repair their mosques without securing permits or paying bribes. Considered by the UN to be “one of the world’s most persecuted minorities,” hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled Burma, includingto India. In a visual storytelling workshop that my husband, 11-year-old daughter and I facilitated in a makeshift Rohingya encampment outside Delhi, 13-year-old Arif painted why he was forced to flee Burma. “I had never seen helicopters shoot bullets before,” he said.

By Arif

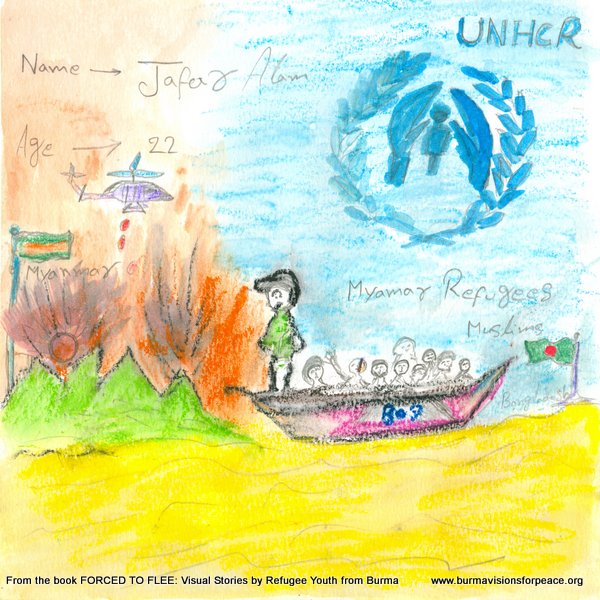

Since then, tens of thousands of displaced and desperate Rohingya have been forced into boats and shoved out into the Bay of Bengal where they have been left adrift. Or they have boarded smugglers’ boats in search of refuge in a neighboring country. Hundreds have died of dehydration or starvation or drowned when their boats were capsized by turbulent seas. Or they have been sold to traffickers. JafarAlamwas among those who fledRakhine State in June 2012, a few weeks before our first visit to the encampment in Delhi. When he and his sea mates discovered that Bangladesh was closed to Rohingya, they continued on to India. South of Delhi, beside a garbage dump, they—and over 200 other Rohingya—set up camp in a wide open field. “For now, this is home,” Jafar said.

By JafarAlam

About 8,000 Rohingya asylum-seekers have reached India. First they must pass through Burma—a risky venture, as Rohingya are forbidden to travel between townships without official permission. A Rohingyamanin the encampment said that he had owned a farm in Rakhine State. “After confiscating my land, the Burma Army picked me up on an extortion bid,” he explained. That was the last straw. He said, "We came to India because it is the land of “raham-karam,” meaning “compassion and grace.” (The red triangles in this map represent Internally Displaced Person (IDP) camps in Rakhine State and, on the other side of the Burma-Bangladesh border,in Cox’s Bazar district.)

This “visual story” was painted by 11-year-old Muhammad Kabiv. Built on a plot of barren land, the 222-person Rohingya encampment in southeast Delhi was made up of some 50 tents, re-purposed tin sheets propped up on bamboo stilts. A local charity had lent the land to the Rohingya after they were forced to abandon their prior camp, near UNHCR-Delhi’s office, a month earlier. They couldn’t understand why UNHCR had turned them away; legal refugee status would have enabled their children to go to school. A grandfather in the campsaid, “Wherever we go, we are chased away.” He prayed that they would not outstay their welcome.

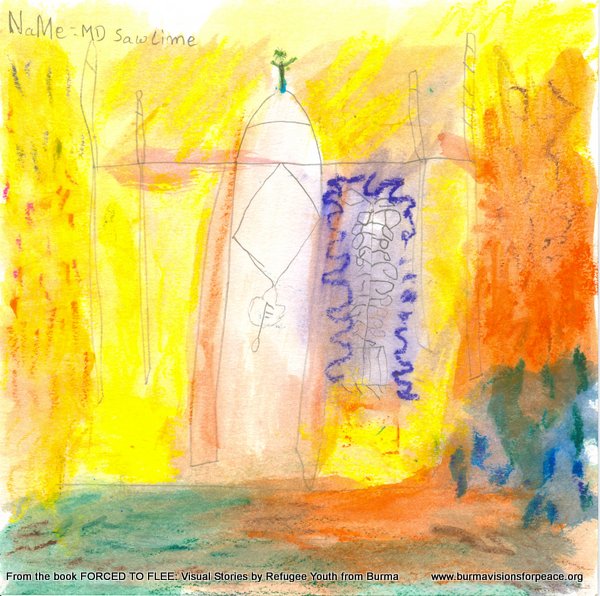

By Saw Lime

Like many residents of the Rohingya encampment, 10-year-old Hamidi dreamed of the minaret in her home town in Rakhine State. She dreamed that it hadn’t been a casualty of the conflicts between Buddhists and Muslims. She dreamed that former neighbors now living in IDP camps in Rakhine State could leave the camps and rebuild their homes and communities, safely. She dreamed of reuniting with her Rohingya friends in front of the minaret, and rediscovering how to live peacefully with her Buddhist friends.

By Hamidi

Forced to Flee illustrates that emotions conveyed and evoked by a single narrative image can tell a story of a thousand words, open hearts and build bridges of understanding. Asthe people of Burma prepare for their upcoming general election, on November 8, this timely collection offers arare child’s-eye view into the lives of the country’s most marginalized and oppressed ethnic minorities, including the Rohingya.

Burma’s democracy movement has reached a crossroads, confronted by a clash in perceptions of its national identity. Clearly, despite recent democratic reforms, the Southeast Asian nation still has a long way to go. A multi-ethnic, multi-religious country, the only way Burma can achieve national reconciliation and sustainable peace is by respecting the rights of its people, all of its people.

If you have been moved by the“visual stories” in this article, please see Forced to Flee’s“Ways to Help” appendix. In addition to concluding thebook, the appendix is available on the book’s website. To learn how to help or to order a copy of the book, please visit www.burmavisionsforpeace.org

Based in Seattle, Erika Berg considers herself a “mid-wife” of stories that illustrate the courage, resilience and irrepressible hope of those forced to flee persecution in their native land.