"Back To Child Labor And Slavery?"

By John Scales Avery

25 March, 2012

Countercurrents.org

Until the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, human society maintained a more or less sustainable relationship with nature. However, with the beginning of the industrial era, traditional ways of life, containing both ethical and environmental elements, were replaced by the money-centered, growth-oriented life of today, from which these vital elements are missing.

Until the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, human society maintained a more or less sustainable relationship with nature. However, with the beginning of the industrial era, traditional ways of life, containing both ethical and environmental elements, were replaced by the money-centered, growth-oriented life of today, from which these vital elements are missing.

According to Adam Smith (1723-1790), self-interest (even greed) is a sufficient guide to human economic actions. The passage of time has shown that Smith was right in many respects. The free market, which he advocated, has turned out to be the optimum prescription for economic growth. However, history has also shown that there is something horribly wrong or incomplete about the idea that individual self-interest alone, uninfluenced by ethical and ecological considerations, and totally free from governmental intervention, can be the main motivating force of a happy and just society. There has also proved to be something terribly wrong with the concept of unlimited economic growth.

In the early 19 th century, industrial society began to be governed by new rules: Traditions were forgotten and replaced by purely economic laws. Labor was viewed as a commodity, like coal or grain, and wages were paid according to the laws of supply and demand, without regard for the needs of the workers. Wages fell to starvation levels, hours of work increased, and working conditions deteriorated.

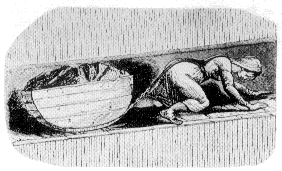

John Fielden's book, “The Curse of the Factory System” was written in 1836, and it describes the condition of young children working in the cotton mills. “The small nimble fingers of children being by far the most in request, the custom instantly sprang up of procuring 'apprentices' from the different parish workhouses of London, Birmingham and elsewhere... Overseers were appointed to see to the works, whose interest it was to work the children to the utmost, because their pay was in proportion to the quantity of work that they could exact.”

“Cruelty was, of course, the consequence; and there is abundant evidence on record to show that in many of the manufacturing districts, the most heart-rending cruelties were practiced on the unoffending and friendless creatures... that they were flogged, fettered and tortured in the most exquisite refinements of cruelty, that they were in many cases starved to the bone while flogged to their work, and that they were even in some instances driven to commit suicide... The profits of manufacture were enormous, but this only whetted the appetite that it should have satisfied.”

With the gradual acceptance of birth control in England, the growth of trade unions, the passage of laws against child labor and finally minimum wage laws, conditions of workers gradually improved, and the benefits of industrialization began to spread to the whole of society. Among the changes which were needed to insure that the effects of technical progress became beneficial rather than harmful, the most important were the abolition of child labor, the development of unions, the minimum wage law, and the introduction of birth control.

One of the important influences for reform was the Fabian Society, founded in London in 1884. The group advocated gradual rather than revolutionary reform (and took its name from Quintus Fabius Maximus, the Roman general who defeated Hannibal's Carthaginian army by using harassment and attrition rather than head-on battles). The Fabian Society came to include a number of famous people, including Sydney and Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, Annie Besant, Leonard Woolf, Emaline Pankhurst, Bertrand Russell, John Maynard Keynes, Harold Laski, Ramsay MacDonald, Clement Attlee, Tony Benn and Harold Wilson. Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first Prime Minister, was greatly influenced by Fabian economic ideas.

The group was instrumental in founding the British Labour Party (1900), the London School of Economics and the New Statesman. In 1906, Fabians lobbied for a minimum wage law, and in 1911 they lobbied for the establishment of a National Health Service.

The reform movement's efforts, especially those of the Fabians, overcame the worst horrors of early 19 th century industrialism, but today their hard-won achievements are being undermined and lost because of uncritical and unregulated globalization. Today, a factory owner or CEO, anxious to avoid high labor costs, and anxious to violate environmental regulations merely moves his factory to a country where laws against child labor and rape of the environment do not exist or are poorly enforced. In fact, he must do so or be fired, since the only thing that matters to the stockholders is the bottom line. One might say (as someone has done), that Adam Smith's invisible hand is at the throat of the world's peoples and at the throat of the global environment.

The movement of a factory from Europe or North America to a country with poorly enforced laws against environmental destruction, child labor and slavery puts workers into unfair competition. Unless they are willing to accept revival of the unspeakable conditions of the early Industrial revolution, they are unable to compete.

Today, child labor accounts for 22 % of the workforce in Asia, 32 % in Africa, and 17 % in Latin America. Large-scale slavery also exists today, although there are formal laws against it in every country. There are more slaves now than ever before – their number is estimated to be between 12 million and 27 million. Besides outright slaves, who are bought and sold for as little as 100 dollars, there many millions of workers whose lack of options and dreadful working conditions must be described as slavelike.

The CRO's of Wall Street call for less government, more deregulation and more globalization. They are delighted that the work of the reform movement is being undone in the name of “freedom”. But is this really what is needed? Perhaps we need instead to reform our economic system to give it both a social conscience and an ecological conscience. Perhaps some of the things that the world produces and consumes today are not really necessary.

Governments already accept their responsibility for education. Perhaps in the future they will also accept the responsibility for insuring that their citizens can make a smooth transition from education to secure jobs. The free market alone cannot do this – the powers of government are needed. Let us restore democracy! Let us have governments that work for the welfare of all their citizens, rather than for the enormous enrichment of the few!

Suggestions for further reading

1. John Fielden, “The Curse of the Factory System”, (1836).

2. Adam Smith, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments”, (1859); D.D. Raphael and A.L. MacPhie, editors, Clarendon, Oxford, (1976).

3. Adam Smith, “An Inquery into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations”, (1776), Everyman edn., 2 vols., Dent, London, (1910).

4. Charles Knowlton, “The Fruits of Philosophy, or The Private Companion of Young Married People”, (1832).

5. John A. Hobson, “John Ruskin, Social Reformer”, (1898).

6. E. Pease, “A History of the Fabian Society”, Dutton, New York, (1916).

7. W. Bowdin, “Industrial Society in England Towards the End of the Eighteenth Century”, MacMillan, New York, (1925).

8. G.D. Cole, “A Short History of the British Working Class Movement”, MacMillan, New York, (1927).

9. P. Deane, “The First Industrial Revolution”, Cambridge University Press, (1969).

John Scales Avery is a theoretical chemist noted for his research publications in quantum chemistry, thermodynamics, evolution, and history of science. Since the early 1990s, Avery has been an active World peace activist. During these years, he was part of a group associated with the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs. In 1995, this group received the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts. Presently, he is an Associate Professor in quantum chemistry at the University of Copenhagen.

Some parts of the article are excerpted from Avery's book, "Crisis 21: Civilization's Crisis in the 21st Century", which can be downloaded freely from several sites in the Internet.

Due to a recent spate of abusive, racist and xenophobic comments we are forced to revise our comment policy and has put all comments on moderation que.