The Sexual Politics of Meat: 25 Years Later

By Mickey Z. Interviews Carol J. Adams

29 August, 2015

Worldnewstrust.com

“The heart-opening work of loving and responding with care to this fragile world and its inhabitants has shaped me as a writer and activist.” - Carol J. Adams

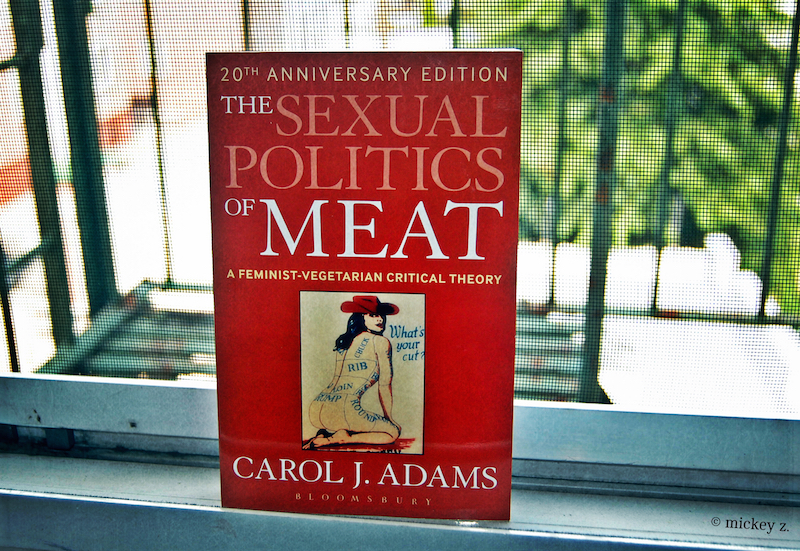

In her 1990 classic, The Sexual Politics of Meat, Carol J. Adams introduced the concept of “the absent referent,” e.g. behind every meal of meat is an absence: the death of the animal whose place the meat takes.

Never content with either single-issueism or dualism, Adams goes on to argue that “male dominance and animals’ oppression are linked by the way that both women and animals function as absent referents in meat eating and dairy production, and that feminist theory logically contains a vegan critique...just as veganism covertly challenges patriarchal society.”

She concludes: “Patriarchy is a gender system that is implicit in human/animal relationships.”

I could go on… and on. Carol’s resume is mind-bogglingly impressive, her work covers the full social justice gamut, and don’t get her started on the topic of vegan cooking! But I’d rather add this: Getting to know Carol has been wonderful. She embodies the empathic spirit of activism and is far more than an iconic byline on an iconic book. Carol is a humble guide, brimming with wisdom and experience, and I’m honored to call her a friend.

With the 25th anniversary edition of The Sexual Politics of Meat due out in October, I thought it’d be the ideal time to catch up with Carol, talk about the book, its impact, and her vision for the future.

It took a little schedule-related juggling, but our conversation (via phone and e-mail) took went a little something like this…

Mickey Z.: While moving and connecting within Occupy Wall Street, I became quite fond of the statements: "All our grievances are connected/All our solutions are connected." As someone who has essentially lived her life by this credo, would you agree that this philosophy is more honored in the breach when it comes to activist circles? That is, it's more likely activists will behave as if all our grievances are discrete entities.

Carol J. Adams: One of the problems is that the burden is on those of us who recognize the oppression of animals to educate human justice activists on the interconnections and we meet up against something I call “Retrograde Humanism,” the belief that we must help humans first then we can think about animals. An example of retrograde humanism is when animal activists are asked (usually angrily), “What are you doing about the homeless?” Sometimes I laugh and say that my animal activism is responsible for more people caring about the homeless than anything else! (I laugh in part because I volunteer at a homeless day shelter my partner oversees) I introduce the idea of “retrograde humanism” in an article called “What Came Before The Sexual Politics of Meat in this anthology. It’s almost as though cultural discussions gravitate to dualisms (i.e., we’re either for people or animals) when dualisms are the problem and not the solution…

MZ: But Carol, isn’t dualism just perfect for memes and tweets of 140 characters?

CJA: Yes! Let’s remember, too, that there are non-profits doing intersectional work, like the Food Empowerment Project, A Well-Fed World, Vine Sanctuary, and Brighter Green. It’s taken many years, but the anti-domestic violence movement recognizes the issue of harm to animals. (My early essay on this subject is in Animals and Women.)

Because people benefit from the oppression of other animals, it is hard for us to get progressives and human rights campaigners to recognize the oppression on the other side of the species line, much less see how the oppressions are interconnected. We have to provoke them to interrogate their own privilege, which they don’t see as privilege but as “the way it is.” Their privilege gives pleasure, the pleasure of eating and viewing and killing and wearing animals. They do not welcome this information. Such an interaction requires a great deal of care.

Another thing to consider is what activists several decades ago referred to as the “primary emergency.” What is the primary emergency that a group is addressing? As animal activists, we need to be sensitive to the primary emergency of any group that we seek to work with intersectionally and not overwhelm that focus. For instance, #BlackLivesMatter is saying: this is our primary emergency.... And who could argue with that, given the statistics on the deaths of African-Americans by police?

It helps for us to ask ourselves, “What is the privilege I am bringing to this situation? What do I need to be aware of that may not be visible to me? What are my presumptions?” In seeking alliances, these are important questions that I hope will keep us from reifying or co-opting someone else’s oppression in our work.

I tried to push this question 20 years ago in my essay “On Beastliness and A Politics of Solidarity” for Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. In that essay, I suggest that some animal activists are willing to address their human privilege, but not their white or male privilege; so the animal rights movement becomes burdened by unexamined privileges. In the past five years, Breeze Harper’s critical race work on veganism offers us the opportunity to recognize and challenge the role of white racism. Yet, instead she reports sometimes being attacked by white vegans for her work.

Unless we are asking the question, “What is the other’s primary emergency?” we are having a conversation only among ourselves.

MZ: Do you feel there ever is just one primary emergency?

CJA: Yes and no. After all, identity is not additive. During the first two decades of the battered women’s movement, it was observed that some therapists were saying to battered women, in a sense, “How does it feel to have a foot on your neck?” What was problematic from an activist’s point of view was that the therapist assumed the woman could not change her situation; she could only ameliorate it and reflect on it. Meanwhile, as activists we were saying, “How do we get the foot off your neck?”

The primary emergency is the foot on the neck. How it is experienced and what resources exist to remove it are influenced by race, class, sex, and ability.

Systematic oppression places the foot on the neck of a group. Systematic oppression also creates and relies on the structure of the absent referent in which the oppressed disappear as unique individuals and become objectified.

MZ: Could you talk more about the absent referent?

CJA: In The Sexual Politics of Meat, I argued that live animals are the absent referents in the concept of meat. The structure of the absent referent functions on three levels: the animals disappear literally, they disappear through language that masks violence, and they disappear metaphorically, when the meaning of their experience of violence is lifted to a “higher” or more imaginative function. But, animals are not the only absent referents in our oppressive culture.

Through the structure of the absent referent, particularity disappears and objectification prevails. The result is the disappearance of a subject (because the subject is a part of a group that experiences social oppression and has been marked) and the re-appropriation of that subject’s experience. The absent referent is both a place of disappearance and intersection.

Once we recognize how the absent referent functions, then in our activisms we try not to perpetuate the absent referent. We try to resist it by exposing it and acknowledging the subjectivity of others who also became absent referents. For instance, the movement #sayhername is showing how many African-American women have been killed by the police and how for quite awhile this was under the radar. Say her name: acknowledge the particular women who had, at one time, been subjects of their own lives.

MZ: In my experience, attempting to introduce intersectionality and create coalitions has often led to ugly confrontations and messy schisms.

CJA: Yes, and it’s important to understand why that is, if we want, as activists, to be both respectful and more successful in our activism.

Intersectional activism isn’t about equivalencies, but about interrelationships. Misogyny is not racism is not speciesism is not homophobia. They are interconnected, not analogical. I believe these oppressions arise from a white patriarchal system of domination. Various forms of oppression will be mobilized in keeping groups down: so attitudes about species can be used to mark race, sex, and disability. And attitudes about the other species are inflected with gender, race, and ableism. Part of the issue for each oppressed group of human beings is how species prejudices are used to describe, oppress, or delimit who they are.

I try to get at it through the absent referent, through the sense that within the structure of the absent referent an interaction/intersection occurs. It’s not an equivalency…

MZ: Can you offer input and suggestions for those activists (not only in animal rights but in other movements like feminism, anti-racism, etc.) seeking to cultivate such cross-awareness and solidarity?

CJA: First, we should acknowledge the dialogical nature of solidarity. We often err in how we stake a claim to the conversation. We want to be listened to, but we don’t want to listen. Intersectional activism is respectful. It acknowledges the traumatic nature at the heart of activism.

Often it seems that what happens is a sort of absolutist creed that can’t have a conversation, can’t allow itself to be contextual, and wraps itself within anger, so that its method and message disrupt solidarity with other groups, saying “Come to us, we don’t have to come you.”

Simone Weil said that attention was the ability to ask “what are you going through?” and being able to listen for an answer. My work, and the work of other feminist animal activists, is to show how this approach—attention, care—applies to human treatment of the other animals. In the introduction to The Feminist Care Tradition in Animal Ethics, Josephine Donovan and I say this question, “What are you going through?” can be asked of nonhuman animals and we will know their answer. But that doesn’t mean we stop listening to other human beings.

We need a little more humility in the movement, at least from some (and probably less from others! Gender dynamics operating here!). Don’t assume you know what all the issues are. Sit with another’s pain, another group’s vision. Learn what the primary emergency of another group is.

Also ask the question “What is the privilege I am bringing to this situation?” and be silent till you know the answer.

We should not cannibalize another movement’s slogan or images. If we do this, we announce that we are not hearing and respecting the primary emergency being articulated. To convert the claim #blacklivesmatter to #alllivesmatter is an example. All lives matter, of course, but the time to make that point is not right now. It’s co-optation. It’s trying to say, “look while we are giving attention to this epidemic of the police shootings of African-Americans, let’s also look at this other problem.” It is also saying, “No you are wrong, race is not the primary emergency.” Where do we get the right to assert this? Not only are we seen as co-opting, we lose the potential future alliances we could be building. We should be saying: “How can we support you?”

MZ: It’s a quarter-century after the initial release of the book, can you look forward and talk about your vision of the next 25 years?

CJA: I'm interested in our methodology, our praxis, of change. I'm not very good when it comes to specifics about the future, but I do have thoughts about how we get there. We don’t really know the possibilities of activism. Empathy can be learned. I would love to see more empathy-based activism rather than positioning the animal rights movement as a “war” against animal oppressors. What if anger isn’t the emotion we start with but compassion? I understand why we are angry; I began writing The Sexual Politics of Meat out of anger. But I had to find a way to subdue and transmute the anger or otherwise the book would have been unreadable.

If discovering we can live without benefiting from so many of the ways the other species are oppressed is transformative, then why aren’t we acting as transformed people? What’s our model for activism based on but male-defined criteria: left-brained, argumentative, scoring points? Where’s incubation, and silence, and trusting interactions, and creativity? Why are we accepting such a limited model?

If it hurts too much to interact with those who are not vegan (and I can understand that feeling, too), then identify ways to be an activist that doesn’t involve frequent interactions with non-vegans. Learn how to articulate you point of view clearly. Write letters to the editor for national magazines, national newspapers, and online. Start a twitter account and tweet about the information you know, retweeting other vegans, and finding valuable information to feed into the twittersphere. Or host vegan meals. Organize a vegan get-together. Go to a senior citizen living area and see if you can start a vegan eating group. There is no one model for being a successful activist. And no, you don’t have to watch another very disturbing video. If you know the information, it’s okay not to add to your own pain.

Learning how much suffering and death is inflicted on the other animals is painful. With this knowledge, what do we do? I believe the world is a very fragile place and I am seeking ways of creating change that doesn’t require traumatizing of others. What would activism look like if it had care at the heart of its insights and tactics?

To connect with Carol and her work, please visit her website!

Mickey Z. is the author of 13 books, most recently Occupy these Photos: NYC Activism Through a Radical Lens. Until the laws are changed or the power runs out, he can be found on the Web here and here. Anyone wishing to support his activist efforts can do so by making a donation here.

"The Sexual Politics of Meat: 25 Years Later" by Mickey Z. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Comments are moderated