Although futurists aren’t supposed to make predictions, the notion that our energy system is switching much more quickly than expected from fossil fuels to renewables, and that solar energy will be at the front of that change, suddenly doesn’t seem so controversial. Of course, the speed of the change still matters, certainly in terms of global warming outcomes.

And yet until recently the notion that solar energy would be the leading energy source was a possible future that was, broadly, regarded as impossible.

As Jeremy Williams notes in a recent review of Chris Goodall’s new book, The Switch, at his blog Make Wealth History:

The International Energy Agency didn’t think that solar power would ever be affordable at any great scale, and didn’t include it in its projections. In 2013, George Monbiot wrote that “solar power is unlikely to make a large contribution to electricity supply in the UK.” Goodall himself admits that he didn’t think it had much to offer until very recently.

Or, as Bloomberg put it:

The best minds in energy keep underestimating what solar and wind can do. Since 2000, the International Energy Agency has raised its long-term solar forecast 14 times and its wind forecast five times.

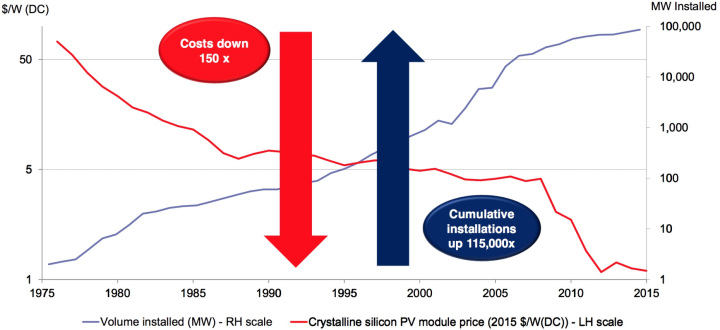

So what’s happened? The answer, in headline form, is in the chart at the top of this post.

Exponential fall

The vertical axes, on both sides, showing costs and installation, are both logarithmic scales, which means that they’re telling us that there’s been an exponential fall in the cost of producing solar PV. It is now the cheapest way to produce electricity in many parts of the world. Even in cloudier and cooler parts such as the UK, the cost of solar is now approaching “grid parity”, at which the cost of solar is the same as the average cost of the overall basket of energy sources for the electricity grid as a whole.

(This is one of the reasons why the vast premium on offer to EDF if it ever builds and runs the Hinkley Point nuclear power station, more than a decade down the line, looks increasingly anachronistic. But that’s a post for another day.)

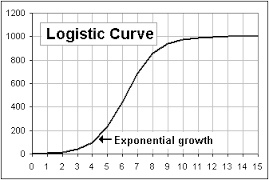

Now, “exponential” is one of those words that gets bandied about dangerously in futurist cicrles. There are people out there who make a good living as keynote speakers from telling their audiences that the world is speeding up, that change is beciming exponential, and that we poor old humans have only linear, arithmetric brains. At some point in the presentation the lily pond gets wheeled out, or thegrains-of-rice-on-the-chessboard parable.

‘It will stop’

I’m sceptical of such broad sweeping claims. The exponential idea is built on the steady progression of Moore’s law over the last 30 years or so; except that this hasnow stopped progressing. As a futurist, I’m more a fan of Stein’s law (“if something can’t go on forever, it will stop”).

But at risk of seeming paradoxical, I think the world’s experts missed the possibility that solar power might see dramatic falls in cost was because their mental models of technological innovation were wrong. As a result, they didn’t expect any exponential change in cost at any time. They assumed–at best–arithmetic or geometric rates of change.

It’s worth unpacking this, not least because these policy assumptions on the future of solar are expensive mistakes. They mean, with the benefit of hindsight, that investment capital has been misdirected. And even if strategy is about the best assumptions you could have made at the time, there are good reasons to believe that strategy would have been better if the mental models of the analysts had also been better.

S-curves

I think the reason why people get confused about this is partly down to Silicon Valley exceptionalism (“Hey, Moore’s Law!”), and partly from taking a long enough view.

The price/performance ratio of every successful technology follows an S-curve, or logistic curve, and it always looks like exponential growth in the middle.

Source: http://www.gummy-stuff.org/logistic-growth.htm

Engineers tend to understand this better than others. It was Bill Sharpe and Ian Welsh, both ex-HP, who observed to me in 2010 or so that the cost of solar was following a logistic curve that meant it would hit grid parity, even in the UK, around the middle of the decade.

Researchers from the Santa Fe Institute and MIT observed in a paper a couple of years ago that Wright’s Law was the best predictor of this exponential phase. It relates cost to production volumes (whereas Moore’s Law connects price/performance improvements to time). Wright’s Law was formulated in 1936 on the basis of cost curves in aviation development.

The IEEE summary of the research summarised the research this way: The paper

compares the performance of six technology-forecasting models with constant-dollar historical cost data for 62 different technologies—what the authors call the largest database of such information ever compiled. The dataset includes stats on hardware like transistors and DRAMs, of course, but extends to products in energy, chemicals, and a catch-all “other” category (beer, electric ranges) during the periods when they were undergoing technological evolution. The datasets cover spans of from 10 to 39 years; the earliest dates to 1930, the most recent to 2009. It turns out that high technology has more in common with low-tech than we thought. The same rules seem to describe price evolution in all 62 areas.

One other point is worth picking up from the researchers’ abstract (opens pdf):

We discover a previously unobserved regularity that production tends to increase exponentially.

Experience curves

In his book, which I haven’t yet read, Goodall calls this the “experience curve”: as we produce more, costs fall. The Bloomberg article put figures on this:

Every time global wind power doubles, there’s a 19 percent drop in cost, according to BNEF, and every time solar power doubles, costs fall 24 percent.

Solar has doubled seven times in 15 years; wind has doubled four times over the same period.

This looks quite a lot like Wright’s law in action, and like the familiar economics idea of “economies of scale”. There’s a second half as well, which one can call “economies of scope”, in which changes in the price to performance ratio also promotes collective learning as the community around the technology expands and makes connections with related technologies.

This second half of the story is an important part of what’s happening with solar. Battery technology is also making significant improvements as car companies turn their attention to an electric vehicle future, along with the development of other innovative storage solutions for solar-generated electricity.

Cycles of disruption

There’s a further consequence. One of the observations that Bill Sharpe has made to me is that when the price-performance ratio of a technology changes by an order of magnitude (i.e., a factor of 10) then the structure of the industry also goes through a structural disruption. In the case of solar, the first effects of this disruption is being seen in the fossil fuels sector.

Suddently, the majority of new energy investment is going into renewables rather than the fossil fuel sector, the balance sheets of coal companies are weak, and those of smaller oil businesses are starting to look shaky, and the divestment case from coal and oil is not just a moral case, driven by global warming, but a financial case, especially for long-term investors such as pension funds.

Andrew Curry started as a financial journalist for BBC Radio 4’s Financial World Tonight, before moving to Channel 4 News during the 1980s. He still maintains an interest in digital media and in the notion of the creative economy.